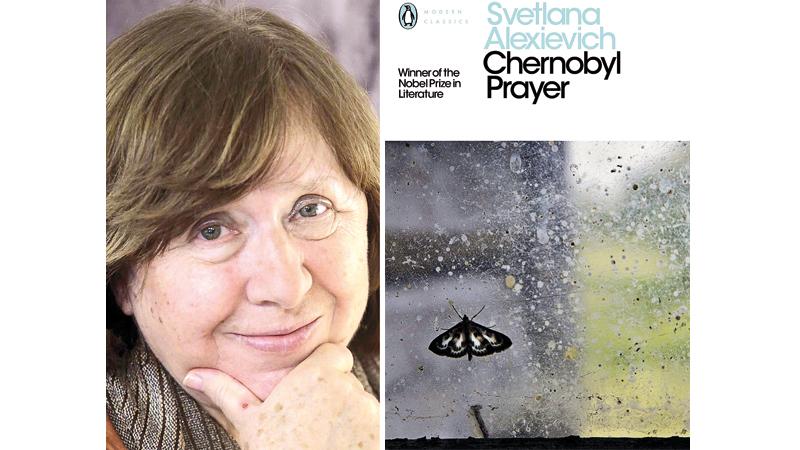

Author – Svetlana Alexievich

Translators – Anna Gunin and Arch Trait

Publisher – Penguin Books

Chernobyl Prayer is Belarusian Nobel Prize winning author and journalist, Svetlana Alexievich’s nonfiction book dealing with the consequences of the Chernobyl disaster, published in 1997 in Russian. The English translation was published in 2016. Svetlana compiles the testimonies from Chernobyl survivors – clean-up workers, residents, firefighters, resettlers, widows, orphans – and crafts their voices into a haunting oral history of fear, anger and uncertainty, and also dark humour and love. She presents the Chernobyl episode so emotionally and heartbreakingly that it is difficult to see the facts of the disaster from an objective point of view.

Monologues

The book comprises a series of monologues by Chernobyl survivors. Reviewing the book Arundhati Roy says it’s “a beautifully written book, it’s been years since I had to look away from a page because it was just too heart-breaking to go on. Julian Barnes reviewing it in the Guardian says the book is “a collage of oral testimony that turns into the psycho¬biography of a nation not shown on any map… The book leaves radiation burns on the brain, while Helen Simpson says it is “one of the most humane and terrifying books I’ve ever read.

Mainly the book has three parts, and the first part titled Land of the Dead, offers monologues of survivors, especially their family members, relatives, neighbours, returnees and other affected people. The second part, named The Crown of Creation presents the monologues of close observers of the disaster. The third part called Admiring Disaster comprises soliloquies of resettled persons, chemical engineers, environmentalists, historians, wives of clean–up workers, scientists, village school teachers, residents of Khoyniki, politicians and journalists.

The book begins with some historical facts about the Chernobyl disaster:

“Belarus…. To the outside world we remain terra incognita: an obscure and uncharted region. ‘White Russia’ is roughly how the name of our country translates into English. Everybody has heard of Chernobyl, but only in connection with Ukraine and Russia. Our story is still waiting to be told.

Narodnaya Gazeta, 27 April 1996

Author cites very interesting facts about the disaster in this chapter:

Blasts

On 26 April 1986, at 01:23 hours and 58 seconds, a series of blasts brought down Reactor No. 4 of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, near the Belarusian border. The accident at Chernobyl was the gravest technological catastrophe of the twentieth century”.

“For the small country of Belarus (population ten million), it was a national disaster, despite the country not having one nuclear power station of its own. Belarus is still an agrarian land, with a predominantly rural population. During the Second World War, the Germans wiped out 619 villages on its territory along with their inhabitants. In the aftermath of Chernobyl, the country lost 485 villages and towns: seventy remain buried forever beneath the earth. During the war, one in four Belarusians was killed; today, one in five lives in the contaminated zone.

That adds up to 2.1 million people, of whom 700,000 are children. Radiation is the leading cause of the country’s demographic decline. In the worst hit provinces of Gomel and Mogilyov, the mortality rate outstrips the birth rate by 20 per cent.

Chernobyl (Minsk: Belorusskaya Entsiklopediya, 1996)

Though all the monologues in the book are very heartbreaking, the first one, A lone human voice which is a monologue of Lyudmila Ignatenko, wife of a deceased fireman is one of the most affecting:

“I don’t know what to tell you about. Death or love? Or is it the same thing. What should I tell you about?

“We were just married. We’d still hold hands walking down the street, even if we were going to the shops. We were together the whole time. I used to say, I love you.ʼ But I couldn’t imagine just how much I loved him. I had no idea. We lived in the hostel for the fire station where he worked. On the first floor. Lived there with three other young families. We all shared a kitchen.

The fire engines were below us, at ground level. Red fire engines. It was his work. I always knew where he was, what he was up to. In the middle of the night, I heard some noise. There was shouting. I looked out the window. He saw me and said, Shut all the windows and go back to bed. The power station’s on fire. I won’t be long…..ʼ (Page 6)

Emotion

Svetlana uses the literary technique of the stream of consciousness to convey the emotion in the monologues. Here, the output is so powerful because she offers real life experiences of survivors. The last pages of the above monologue is as follows:

“I had no desire at all to live. At night, I used to stand at the window, staring at the sky.Vasya, what should I do? I don’t want to live without you.ʼ In the daytime, I’d be passing the kindergarten and would stop and stand. I would have happily looked at the children for hours. I was going crazy! And at night I began asking, Vasya, I’d like a baby. I’m frightened of being alone. I can’t take it anymore, Vasya!ʼ Or another time I asked, Vasya, I don’t need a man. No one could ever be better than you. But I want a baby.ʼ (Page 22)

Recording testimonies

A Russian writer and critic, Dmitry Bykov attributes Svetlana’s art of writing to Belarusian writer Ales Adamovich, who felt that the best way to describe the horrors of the 20th century was not by creating fiction but through recording the testimonies of witnesses. Belarusian poet Uladzimir Nyaklyayew called Adamovich “her literary godfather.

The last monologue in the book is narrated by Valentina Timofeyevna Apanasevich, wife of a clean–up worker and shows how emotional and heartbreaking is Svetlana’s art of writing. Her writing style was introduced by the 2005 Swedish Nobel Committee thus, “for her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time. So, this is the last chapter of the last monologue in the book:

“How can I go on living? I haven’t told you everything, not all of it. I was happy, madly happy. There are secrets…. Perhaps you shouldn’t include my name…. People say their prayers in private. To themselves…. (Trails off.) No, put my name! It will be a reminder to God…. I want to know, I want to understand why we should have to bear this sort of suffering? What’s it for? At first, it seemed that after everything that had happened something dark would appear in my eyes, something alien.

I wouldn’t be able to endure it. What saved me? What forced me back towards life? Brought me back? My son. I have another son… The first baby I had with him. He’s been ill for a long time. He’s grown up now, but sees the world through the eyes of a child, the eyes of a five–year–old. I want to be with him now.

I hope to exchange my apartment for one closer to Novinki, the mental hospital there, where he’s lived all his life. That was the verdict of the doctors: for him to live, he needed to be there. I go every day. When he sees me, he asks, Where is Daddy Misha? When will he come?ʼ Who else could ask me that? He’s waiting for him.

“We will wait for him together. I will say my Chernobyl prayer, and he will look at the world with the eyes of a child…