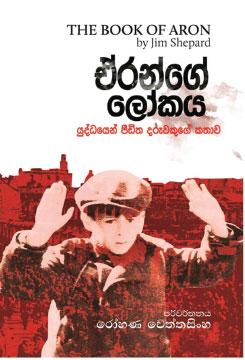

Aronge Lokaya

Translator: Rohana Wettasinghe

Sarasavi Publishers, Nugegoda

Price: Rs 575

Rohana Wettasinghe’s Aronge Lokaya is the authentic Sinhala translation of Jim Shepard’s award-winning novel “The Book of Aron.”

Jim Shepard has always been fascinated by history. Even his short stories are packed with historical references, bibliographies and acknowledgements that make him an intellectually driven research student. Even his fictional characters appear as real-life figures. Shepard’s short stories simply show that humanity is inherently flawed.

Aronge Lokaya is set in the Warsaw ghetto and brings to life an indisputably great man, the child advocate Janusz Korczak who runs an orphanage and entrusts his charges to Treblinka. However, Aronge Lokaya is the story of a misbegotten boy born in Poland at a disastrous time. His antics exasperate his father who used to beat him mercilessly. Even his loving mother is worried about his behaviour. The trouble greater than Aron’s is the general squalour of life among the Jews in the Polish countryside. The story unfolds with World War II. Jews are plagued with sickness, poverty, bad teeth, disaster and death. They face such calamities even before the arrival of the Nazis on their soil.

Aron tries to be a better person. Some of his utterances are touching: “I lectured myself on walks. I made a list of ways I could improve myself.” He takes to books like a duck to water. He loves his mother. In the quiet of the night mother and son make a special bond which remains Aron’s only link to humanity. Even when his father gets a job at his cousin’s factory, the situation of his family does not improve. Then they move to Warsaw. Germans invade Poland and all the Jews are shunted into the ghetto. They move into small apartments and sleep in hallways. German soldiers beat Aron’s father and send his brothers to labour camps. Aron joins a gang and begins to steal and smuggle whatever they lay their hands on. Meanwhile, Aron befriends a Jewish police officer who turns him into an ambivalent informant.

Shepard’s loyalty to historical records is impressive. However, what makes Aronge Lokaya a work of art is his obedience to the boy’s restricted perspective. To make Aron a credible character Shepard has done copious research into Jewish-Polish family life of the 1930s. The reader at once notes the elevated diction and metaphors. The author finds no other way to rebuke the Nazis who think that Jewish life is utterly worthless. Aron is a perfect nobody of a kid who is historically irrelevant, but remains one among the hordes of Jews. Aron mirrors the pathetic life in the ghetto. No one knows what is coming next and Jews are like credulous children under the Nazi’s indiscriminate lash.

Aronge Lokaya brings to life something you have never experienced before. In addition, there are bleak ironies and dark comic exchanges throughout the novel. Humour has no place when Jews are faced with Nazi oppression. However, despite terrible circumstances, Aron and his family find certain things that amuse them. Towards the end of the novel, Aron loses his family, home and sustenance. While he is freezing to death on the street, he is rescued by Korczak. “We’re walking tombstones” he says to his assistant Madame Stefa whose only happiness lies in Korczak. But he cannot reciprocate her feelings and says, “I exist not to be loved, but to act.” They are the words of a monomaniacal and self-martyring machine.

Despite illness Korczak makes a trip into the wider world in search of money and food for the orphans under his care. He begins to admire Aron who no longer needs to make lists on how to improve. Their friendship is based on the circumstances common to both of them. He prompts Aron to act selflessly in a way his mother would not have dared to dream. Aron, once a questionable boy becomes a loving human being.

Aronge Lokaya offers no reassurance to a world the fate of which is sealed. The last pages of the novel are quite shattering, but Shepard has done a marvellous job of reclaiming an insignificant voice and deploying it to observe a great man. The novelist has turned hell into a testament of love and sacrifice. Rohana Wettasinghe has captured the essence of the novel in his translation. Quite unwittingly, he has translated a moving masterpiece.