On World Elephant Day, attention turns to the unique challenges faced by Sri Lanka in the realm of human-elephant conflict (HEC). HEC’s escalating toll paints a stark reality. Human communities endure property damage, crop loss, and tragic fatalities, amplifying poverty and socio-economic instability.

In 2022, as per the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC), Sri Lanka documented 145 human fatalities resulting from HEC. Simultaneously, elephants face habitat loss, injuries, and mortality due to retaliatory killings and encounters with human settlements. DWC reported a substantial rise in elephant mortality, reaching a peak with 433 deaths in 2022. Therefore, the urgent need for implementing effective solutions to minimise HEC in the country becomes paramount.

In 2022, as per the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC), Sri Lanka documented 145 human fatalities resulting from HEC. Simultaneously, elephants face habitat loss, injuries, and mortality due to retaliatory killings and encounters with human settlements. DWC reported a substantial rise in elephant mortality, reaching a peak with 433 deaths in 2022. Therefore, the urgent need for implementing effective solutions to minimise HEC in the country becomes paramount.

Understanding the conflict

The HEC is one of the widespread environmental issues with severe socio-economic and political implications in Sri Lanka. It arises from numerous reasons, wherein the competition for resources and land between humans and elephants being the most prominent (see Figure 1).

Rapid urbanisation, encroachment into elephant habitats, conversion of forests for agriculture, and other infrastructure development projects such as road infrastructure have disrupted the elephants’ traditional migration patterns and fragmented their habitats. Consequently, elephants often venture into human settlements in search of sustenance, leading to conflicts that endanger both elephants’ and human lives.

Consequences and costs

The HEC in Sri Lanka inflicts severe consequences on both humansand elephants. As far as the number of incidents affecting humans is concerned, crop damages are the most prominent type of damage induced by wild elephants, followed by property damage. Deaths, and injuries to humans are the other types of damage that can be seen quite often (see Figure 2).

Sumanadasa, a farmer in Galgamuwa, shared his experience of frequent elephant raids on their crop lands. He said, “As a farmer, my family depends on the crops we cultivate for our livelihood. However, the constant raids by elephants have taken a toll on our lives. We wake up each morning with anxiety, not knowing if our fields were destroyed overnight. Our hard work and investment go in vain as elephants trample and devour our crops. It has become a struggle to provide for our family and maintain a sustainable income.”

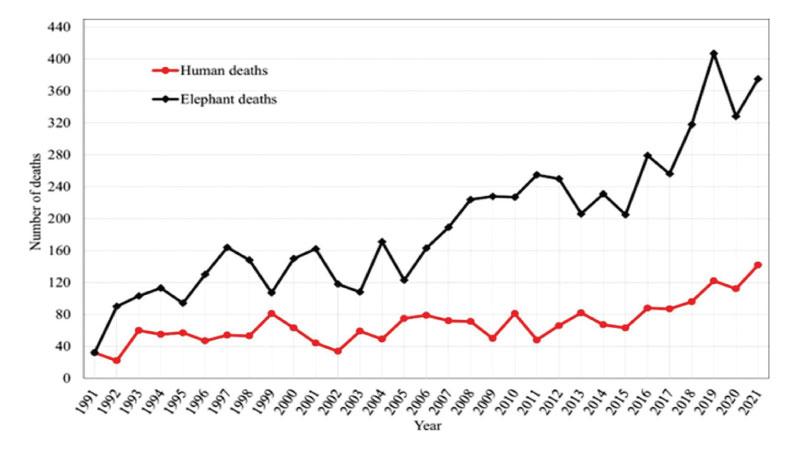

These heart-wrenching stories highlight the profound impact of the HEC on individuals and communities. Beyond the economic losses, the emotional trauma and loss of human lives are immeasurable. The alarming increase in human and elephant fatalities resulting from HEC in Sri Lanka underscores the gravity of the situation (Figure 3).

The average annual human death rate due to the HEC increased by around 42 percent from 1992 to 2021, with the 2021 figure reaching 142 deaths. Despite fluctuations, the number of HEC-caused human deaths has consistently exceeded 100 per year over the past three years, resulting in 2,111 human and 5,954 elephant casualties in the past 30 years. Crop damages also emerge as a pervasive and severe issue.

An IPS study revealed that among the crops grown in HEC-prone areas, paddy is the most vulnerable crop for elephant attacks, following coconut and banana. Farmers have also altered their cropping seasons due to this wild elephant risk.

Likewise, elephants experience notable repercussions that, on certain occasions, culminate in their demise. The DWC reports that the primary causes of elephant mortality are attributed to HEC induced factors (see Figure 4). Two major causes,: hakkapatas (chew bombs) and gunshots, account for over one-third of the HEC induced elephant fatalities, with another 12 percent attributed to electrocution.

Likewise, elephants experience notable repercussions that, on certain occasions, culminate in their demise. The DWC reports that the primary causes of elephant mortality are attributed to HEC induced factors (see Figure 4). Two major causes,: hakkapatas (chew bombs) and gunshots, account for over one-third of the HEC induced elephant fatalities, with another 12 percent attributed to electrocution.

These incidents underscore the urgency to address the HEC and safeguard both human well-being and the conservation of elephants.

Policy initiatives and innovative solutions

Recognising the urgency of addressing the HEC, Sri Lanka has undertaken various policy initiatives and conservation efforts. Some of these are institutionally arranged measures while some are voluntary adjustments by affected communities.

The DWC plays a crucial role in mitigating conflicts, implementing institutionally arranged measures such as creating elephant corridors, elephant drives, thunder flashes distribution, habitat enrichments and installing electric fences to reduce human-elephant interactions. Additionally, community-based conservation projects involving local communities in decision-making have shown promising results in promoting peaceful coexistence in some parts of the country.

As a multifaceted approach to mitigating the HEC, the DWC has been implementing the “Gaja Mituro” program since 2008. Under this, the DWC launched mitigating measures in 58 Divisional Secretariat Divisions (DSD) of 18 Districts.

Residents in affected areas practise numerous voluntary measures to deter problems from elephants. Some examples of voluntary measures include erecting watch huts, creating noise (e.g., firing thunder flashes, shouting), establishing biological fences, and using lighting methods such as fires, kerosene lamps, flares, and flashlights to frighten and chase away the elephants.

However, none of the mitigation measures has given a perfect solution due to various limitations. For instance, some elephants develop adaptive behaviour to actions such as thunder flashes, thus making those no longer effective against them.

Hence, to effectively manage the HEC, innovative solutions are imperative, and the Government, academia, and other stakeholders should pursue innovative approaches and optimal strategies to effectively tackle the issue of the HEC in Sri Lanka.

Technology-driven approaches, including using infrared cameras, drones, sensor-based systems, and satellite imagery to detect habitat monitoring and elephant movements and then using mobile communication systems to alert nearby communities in real-time (early warning system), can help prevent conflicts.

Through educational programs in schools and community outreach initiatives, a sense of responsibility can be instilled while highlighting innovative market-based solutions such as insurance. An IPS study found that insurance as a market-based solution can deliver promising results. These solutions can be complemented by agro-ecological practices such as cultivating elephant-resistant crops, bee-fencing and establishing community-managed buffer zones around protected areas.

Conclusion

As World Elephant Day serves as a powerful global platform for raising awareness on elephant conservation, Sri Lanka can capitalise on this occasion to promote understanding, empathy, and conservation values within local communities.

It is crucial to acknowledge that no single solution can entirely address the complexities of the HEC issue, given its regional variations, changes in elephant behaviour, and diverse human activities. Therefore, adopting a holistic approach that combines suitable traditional methods alongside innovative strategies, involving local communities, and considering the conflict’s ecological, economic, and social aspects becomes essential for effective and sustainable HEC mitigation.

Collaboration among Government agencies, conservation organisations, and local communities becomes paramount in achieving a harmonious coexistence where elephants roam freely, and humans thrive.

The writer is a Research Officer at the Institute of Policy Studies