Money laundering and terrorist financing pose significant challenges for governments worldwide, with Sri Lanka being identified as a hotspot for both illicit activities. Among various money laundering techniques, Trade-Based Money Laundering (TBML) emerges as a particularly hazardous form, warranting close attention from government authorities, financial institutions, academics and the public.

Due to the intricacies of methods employed by criminals, defining and understanding TBML has proven challenging. This article delves into the intricate nexus of money laundering and terrorism financing in Sri Lanka, with a specific focus on the phenomenon known as TBML. The Palermo Convention in 2000, provides a comprehensive definition of money laundering as the act of concealing or disguising the illicit origin of property acquired through criminal offences.

Terrorism financing, as defined by the International Labour Organization, pertains to the willful provision or collection of funds with the intent to support terrorist activities. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in 2006, characterises TBML as the process through which criminal proceeds are obscured by manipulating trade transactions to appear legitimate.

Sri Lanka, classified as a developing country, confronts substantial challenges concerning money laundering and terrorism financing. This vulnerability is evident from its inclusion in the blacklist by the European Union (EU) Commission and the FATF, highlighting the country’s susceptibility to illicit financial activities.

Among the various money laundering techniques, TBML stands out as a significant concern, wherein illegally obtained funds are camouflaged as legitimate earnings through trade transactions. With advancements in international financial market regulations against Money Laundering (ML), criminals have shifted focus to the trade sector, thereby elevating trade-related risks.

In recent years, both developed and developing countries have adopted liberal policies for international financial markets, inadvertently providing avenues for criminals to launder their illicit proceeds through diverse means. Among these techniques, TBML emerges as a favoured method for criminals seeking to cleanse their illegal profits. TBML’s scope encompasses trade activities involving imports and exports, exploiting variations in prices, quantity and quality of goods, alongside practices such as over and under-invoicing, multiple invoicing, false declarations, and phantom shipping.

Illegal financial flow

As per the literature, Sri Lanka faces the potential risk of TBML perpetrated by criminals. It is estimated that the country experiences an annual illegal financial flow of approximately USD 3 billion. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists in 2022 has reported numerous instances of capital flights undertaken by persons and businesses in Sri Lanka to various destinations globally. Notably, Transparency International has identified several countries, including Seychelles, Thailand, Singapore, Bangladesh, Mauritius, India, the Maldives, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and the British Virgin Islands, as attractive destinations for the outflow of illicit cash from Sri Lanka.

Analysing the Global Financial Integrity report from April 2017, which assessed overall illicit financial flows to and from developing countries from 2005 to 2014, it is revealed that the total trading volume during the specified period amounted to $232,325.00 million. Illicit financial outflows ranged between 4 and 7 percent, while inflows ranged between 6 and 11 percent. Trade misinvoicing contributed to inflows of 5-11 percent and outflows of 3-6 percent.

As per the literature, Sri Lanka experiences an average yearly illicit financial flow of USD 3 billion. Investigations by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists have uncovered instances where covert shell companies and trusts facilitated the movement of more than $18 million to tax havens. Swiss leaks also disclosed $58.3 million associated with clients linked to Sri Lanka, further corroborating the presence of illegal capital flights from Sri Lanka to tax havens.

The present analysis establishes that terrorist organisations, including the LTTE, have exploited TBML as a means to launder illicit earnings. Informal trade between India and Sri Lanka has been shown to involve substantial informal money transfers like Undiyal, with transactions often being under or over-invoiced. This creates a vulnerability to money laundering activities, alongside narcotics transshipment, fraud and other illegal practices.

Despite the potential risks associated with TBML, the prevailing literature indicates a lack of attention from stakeholders in addressing this issue. Stakeholders need to recognise that TBML can involve under-banking networks, such as Hawala or Undiyal, which obfuscate transactions and impede economic gains for nations.

The World Customs Organization (WCO) has identified customs administrations as strategically positioned to combat money laundering in global trade systems. However, information gaps in shipping, import/export, pricing, and customs hinder the efforts of compliance officers.

To effectively combat TBML and terrorism financing, cooperation among various entities is crucial. Customs administrations play a pivotal role, yet collaboration with financial institutions, the government entities and other legal authorities is essential.

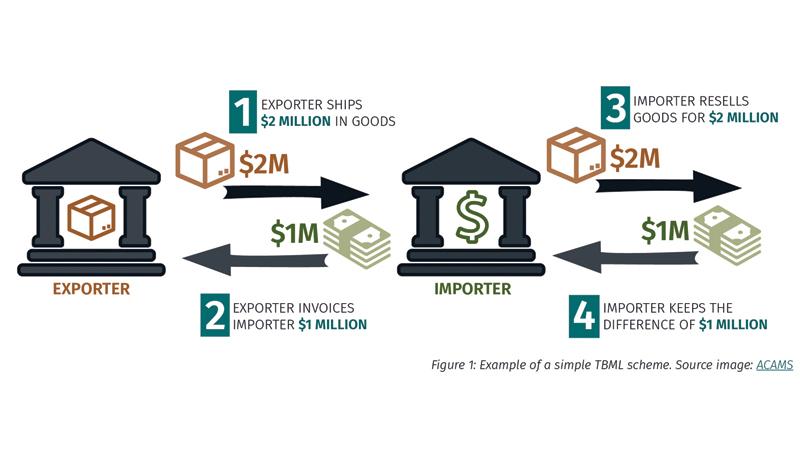

Criminals employ a variety of techniques to facilitate the process of TBML and conceal their illicit earnings. These techniques include over and under-invoicing, over and under shipment (commonly known as “Phantom shipping”), multiple invoicing, and falsely declaring goods and services.

Over and under-invoicing involves misrepresenting the price of goods or services during trade transactions to transfer values, with both importers and exporters collaborating in this deception. For instance, an under-invoicing case example involves the transfer of $10 million of illicit funds from India to Sri Lanka through the purchase of 500 gold rings at $2,000 per ring, which are subsequently exported to Sri Lanka at a price of $1,000 per ring, resulting in a total export value of $500,000. In this manner, the $10 million worth of illicit money is converted into gold and invoiced accordingly, allowing the laundered money to go unnoticed. Conversely, an over-invoicing case example demonstrates how a criminal can launder $10 million from Sri Lanka to Pakistan by setting up an export company in Pakistan, purchasing 100,000 electronic devices for $0.10 per device, and exporting them back to Sri Lanka at a significantly inflated price of $100 per device, resulting in an export value of $10 million.

The technique of over and under shipment (Phantom shipping) entails the misrepresentation of goods or services, including instances where no actual product is moved between jurisdictions. Both the importer and exporter are complicit in this deceptive practice. For example, in an over and under shipment case example, a Sri Lankan company sells 1 million toys to a company in Dubai at $1 each but falsely ships 1.5 million toys. The Dubai company then settles $1 million with the Sri Lankan company through wire transfer, and the rest of the toys are sold, with the remaining payment settled according to the Sri Lankan company’s instructions.

Another technique used in TBML is multiple invoicing, whereby existing documentation is reused to justify multiple payments. Criminals may exploit this method further by reusing the same documents across various financial institutions to avoid detection. For instance, money launderers may issue multiple invoices for the same trade transaction, producing various justifications such as amendments to payment terms or corrections to previous payment instructions. This technique does not necessarily involve misrepresenting the price, quality, or quantity of goods.

Misrepresentation

Lastly, the technique of falsely declaring goods and services involves misrepresenting the quantity, quality, or type of goods or services to justify the movement of value. For example, inexpensive goods may be described as more expensive or entirely different items to justify the value being moved. These various techniques underscore the complexity and significance of TBML as a means for criminals to facilitate the flow of illicit funds across international trade transactions.

The prevention of TBML remains a critical concern worldwide, and the Financial Action Task Force, an intergovernmental organisation, plays a pivotal role in developing and promoting global anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CFT) standards. To address TBML, the FATF has issued guidelines and best practices, emphasising the importance of raising awareness among stakeholders through training and other requisite measures.

The Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) is tasked with gathering financial intelligence and analysing data, making it a central agency responsible for enforcing TBML prevention. Additionally, the customs department, with its comprehensive knowledge of international trades, goods flows, and the global supply chain, assumes a crucial role in curbing TBML. To facilitate coordinated efforts, the FATF recommends establishing interagency groups, public-private partnerships, and coordination bodies to facilitate information sharing and take national actions.

In the context of Sri Lanka, a developing country seeking foreign direct investments, it is essential to consider these indicators and ensure that potential loopholes for criminal exploitation are minimised. Trades such as gold, precious metals, minerals, auto parts, vehicles, agricultural products, foodstuffs, clothing, second-hand textiles, and portable electronics have been flagged by the FATF as having TBML potential. Particular businesses, such as those rapidly expanding into existing markets, displaying irregular cash payments to unidentified third parties, engaging in overly intricate supply chains with numerous transshipments, or venturing into unrelated industries unexpectedly, are also considered susceptible to TBML.

Given Sri Lanka’s potential vulnerability to criminal proceeds and terrorist activities, identifying countries that may facilitate money laundering poses a challenge. TBML serves as a method for transferring illegal earnings, and uncovering potential countries that could assist in such activities would aid regulatory bodies in taking action to prevent illicit proceeds through businesses and trades.

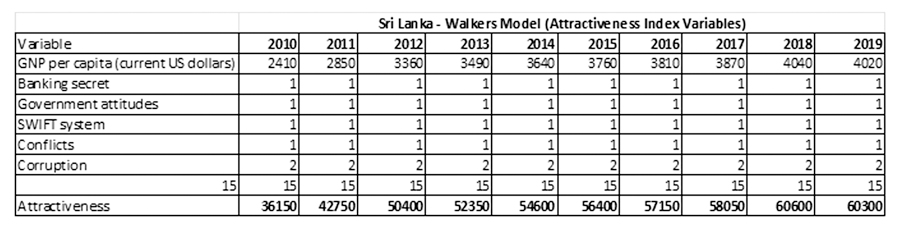

The Walker’s Gravity Model is considered a significant approach for estimating the flow of illicit money between nations, thereby facilitating measures to prevent financial abuse on a global scale. While international regulators have explored several estimation models, Walker’s Gravity Model and its development by Prof. Unger, known as Unger’s model, stand out as effective methods for estimating illegal financial flows. Based on Newton’s universal law of gravity, Walker’s model posits that the attraction between two objects relies on their mass and the squared distance between them, along with a constant factor. Prof. Unger further refined the variables in the model to calculate the outflow of illegal money from the country.

Notably, Walker’s Gravity Model has been employed in various studies to assess illicit migration flows and global illegal financial movements. For instance, M. Anein 2014, utilised the model to estimate illegal migration flows from Turkey to Romania. The International Monetary Funds (IMF) has also acknowledged the significance of the Walkers Gravity Model, confirming its continued relevance in measuring illegal financial flows globally.

Several countries have been carefully chosen for the implementation of Walker’s Gravity model, aimed at comprehending the magnitude of illegal flows entering Sri Lanka. The provided data on these volumes is as follows:

Walkers Gravity Model

Fij/Mi = (GNP/capita)j * (3BSj+GAj+SWIFTj – 3CFj – CRj +15)/ Distanceij2

Fij / Mi – the share of offenders’ incomes transferred from country i to country j

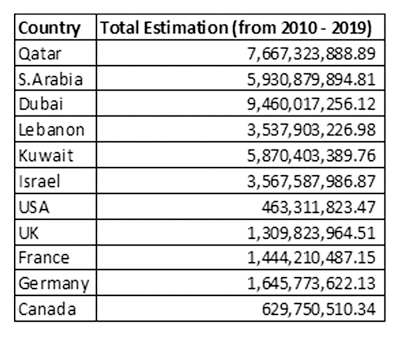

To assess the potential amount of illicit funds that might have been transferred to Sri Lanka, a selection of countries was made through a random sampling process for this study. The chosen countries include Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Dubai, Lebanon, Kuwait, Israel, United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Canada. The data collection for this estimation encompasses the period from 2010 to 2019, with a focus on identifying and analysing illegal earnings that may have been laundered into Sri Lanka during this time frame.

Table 1: The Attractiveness Index

Based on the attractiveness, the approximate laundered amount in Rs. has been calculated during the period from 2010 to 2019.

Table 2: Total Estimation in LKR

According to the findings presented in Table 2, Dubai appears to be a potential country through which proceeds could be laundered into Sri Lanka. In light of this discovery, it is imperative for the authorities to implement additional due diligence measures for transactions originating from Dubai. By doing so, they can effectively combat Trade-Based Money Laundering (TBML) and other illicit laundering processes within the financial institutions.

Having estimation values for each country is instrumental in this endeavour, as it equips compliance experts with the tools to conduct Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD). Through EDD, the true nature of transactions can be thoroughly scrutinised, aiding in the identification of any suspicious activities.

Having estimation values for each country is instrumental in this endeavour, as it equips compliance experts with the tools to conduct Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD). Through EDD, the true nature of transactions can be thoroughly scrutinised, aiding in the identification of any suspicious activities.

This, in turn, empowers the authorities to gain further insights into the trades or business dealings between Sri Lanka and other countries. With such insights, the authorities can take proactive measures to prevent TBML and other potential illicit activities, safeguarding the integrity of the financial system and protecting the country from illicit financial flows.

Conclusion

The gravity model, which is connected to the input-output model, proposes that the volume of trade between two locations is influenced by factors such as population density in location A, the attractiveness of location B to people based in location A, and the distance between the two locations.

To address this critical issue, it is imperative for responsible authorities to proactively tackle TBML. Stakeholders across sectors should receive comprehensive education and awareness about TBML, accompanied by the implementation of preventive measures.

The study also identifies the Undiyal banking system as a potential threat to the economy due to its lack of records or physical cash movement, making it susceptible to TBML exploitation.

While the Central Bank of Sri Lanka plans to introduce LCs-based trading operations to mitigate illegal trade methods, regularisation rather than outright banning of Undiyal transactions may prove to be a more prudent approach, given the system’s long-standing historical significance.

Walker’s Gravity model is recommended as an estimation tool to gauge illegal flows between countries, empowering responsible authorities to exercise heightened due diligence.

The FATF also endorses such models to increase the awareness of potential countries and activities among financial institutions and the regulatory authorities.

However, it is essential to navigate this issue cautiously, especially considering Sri Lanka’s ongoing economic crisis and the potential misuse of relaxed foreign investment rules by criminals seeking to profit illegally. Strategic Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) with top trading partner countries can prove instrumental in preventing TBML operations, demanding close collaboration and vigilance from both ends.

As technology advances, TBML may diversify from traditional fiat currencies to virtual forms, such as virtual currency and virtual assets. Urgent attention is required to address TBML in its evolving complexity to prevent a potential financial collapse in Sri Lanka. The government must exercise utmost care while addressing this sensitive matter, considering the potential ramifications for the country’s economic stability and reputation.

Note: In the Sri Lankan context, the area of publication holds paramount importance as a critical and time-sensitive requirement. The authors are committed to conducting ongoing research in the domains of money laundering and terrorist financing, with the findings being publicly disseminated on a monthly basis.