Part 23

Continued from last week

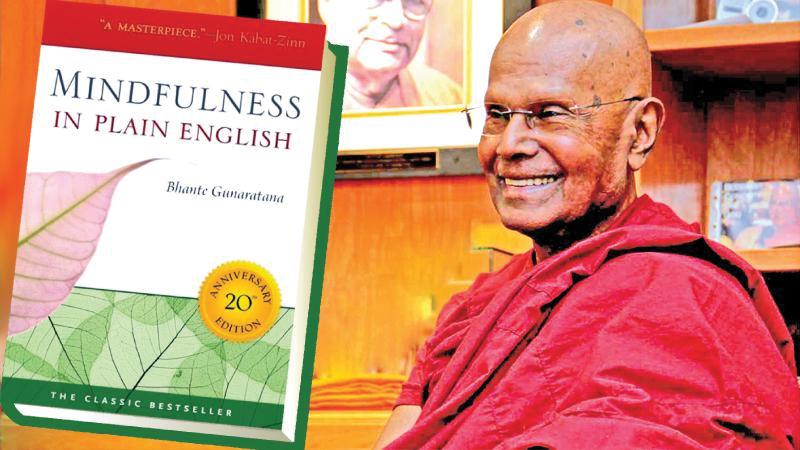

Extracted from renowned meditation guru Bhante Henepola Gunaratana’s Mindfulness in Plain English. The full text of the book was carried in the Sunday Observer in installments.

Dealing with anger

When we are angry with someone, we often latch on to one particular aspect of that person. Usually it’s only a moment or two, enough for a few harsh words, a certain look, a thoughtless action. In our minds, the rest of that person drops away. All that is left is the part that pushed our buttons. When we do this, we are isolating one miniscule fraction of the whole person as something real and solid.

We are not seeing all the factors and forces that shaped that person. We focus on only one aspect of that person—the part that made us angry.

Over the years, I have received many letters from prisoners who are seeking to learn the Dhamma. Some have done terrible things, even murder. And yet they see things differently now and want to change their lives. There was one letter that was particularly insightful and deeply touched my heart. In it, the writer described how the other inmates shouted and jeered whenever the guard appeared. The inmate tried to explain to the others that this guard was also a human being, but the others were blinded by hatred. All they could see, he said, was the uniform, not the man inside it.

When we are angry with someone, we can ask ourselves, “Am I angry at the hair on that person’s head? Am I angry at his skin? His teeth? His brain? His heart? His sense of humor? His tenderness? His generosity? His smile?” When we take the time to consider all the many elements and processes that make up a person, our anger naturally softens. Through the practice of mindfulness, we learn to see both ourselves and others more clearly. Understanding helps us to relate to others with loving friendliness. Within each of us is a core of goodness.

In some, as in the case of Angulimala, we cannot see this true nature. Understanding the concept of “no-self” softens our heart and helps us forgive the unkind actions of others. We learn to relate to ourselves and others with loving friendliness. But, what if someone hurts you? What if someone insults you? You may want to retaliate—which is a very human response. But, where does that lead?

“Hatred is never appeased by more hatred,” it says in the Dhammapada. An angry response only leads to more anger. If you respond to anger with loving friendliness, the other person’s anger will not increase. Slowly it may fade away. “By love alone is anger appeased,” continues the verse in the Dhammapada.

“Hatred is never appeased by more hatred,” it says in the Dhammapada. An angry response only leads to more anger. If you respond to anger with loving friendliness, the other person’s anger will not increase. Slowly it may fade away. “By love alone is anger appeased,” continues the verse in the Dhammapada.

An enemy of the Buddha named Devadatta concocted a scheme to kill the Buddha. Having enraged an elephant with alcohol, Devadatta let him loose at a time and a place Devadatta knew the Buddha would be. Everyone on the road ran away. Everyone who saw the Buddha warned him to run away. But the Buddha kept on walking. His devoted companion, the Venerable Ananda, thought he could stop the elephant. When Ananda stepped in front of the Buddha to try to protect him, the Buddha asked him to step aside; Ananda’s physical strength alone surely could not stop this elephant. When the elephant reached the Buddha, his head was raised, his ears were upright and his trunk was lifted in a mad fury.

The Buddha simply stood in front of him and radiated loving, compassionate thoughts toward the animal—and the elephant stopped in his tracks. The Buddha gently raised his hand up with his palm towards the beast, sending him waves of loving friendliness. The elephant knelt down before him, gentle as a lamb. With the power of loving friendliness alone, the Buddha had subdued the raging animal.

The response of anger to anger is a conditioned response; it is learned rather than innate. If we have been trained from childhood to be patient, kind, and gentle, then loving friendliness becomes part of our life. It becomes a habit.

Otherwise anger becomes our habit. But even as adults, we can change our habitual responses. We can train ourselves to react in a different way.

There is another story from the Buddha’s life that teaches us how to respond to insults and harsh words. The Buddha’s rivals had bribed a prostitute named Cinca to insult and humiliate the Buddha. Cinca tied a bunch of sticks to her belly underneath her rough clothes in order to look like she was pregnant. While the Buddha was delivering a sermon to hundreds of people, she came right out in front of him and said, “You rogue. You pretend to be a saint preaching to all these people. But look what you have done to me! I am pregnant because of you.”

Calmly, the Buddha spoke to her, without anger, without hatred. With his voice full of loving friendliness and compassion, he said to her, “Sister, you and I are the only ones who know what has happened.” Cinca was taken aback by the Buddha’s response. She was so shocked that on the way back she stumbled. The strings that were holding the bundle of sticks to her belly came loose. All the sticks fell to the ground, and everyone realised her ruse. Several people in the audience wanted to beat her, but the Buddha stopped them. “No, no. That is not the way you should treat her. We should help her understand the Dhamma. That is a much more effective punishment.” After the Buddha taught her the Dhamma, her entire personality changed. She too became gentle, kind, and compassionate.

When someone tries to make you angry or does something to hurt you, stay with your thoughts of loving friendliness towards that person. A person filled with thoughts of loving friendliness, the Buddha said, is like the earth. Someone may try to make the earth disappear by digging at it with a hoe or an ax, but that is a futile act. No amount of digging—not in one lifetime or many lifetimes—makes the earth vanish. The earth remains, unaffected, undiminished. Like the earth, a person full of loving friendliness is untouched by anger.

In another story from the Buddha’s life, there was a man named Akkosina, whose name means “not getting angry.” But in fact, this man was exactly the opposite: he was always getting angry. When he heard that the Buddha never got angry with anyone, he decided to visit him. He went up to the Buddha and scolded him for all sorts of things, insulting him and calling him awful names.

At the end of his tirade, the Buddha asked this man if he had any friends and relatives. “Yes,” he replied. “When you visit them, do you take them gifts?” “Of course,” said the man. “I always bring them gifts.” “What happens if they don’t accept your gifts,” the Buddha asked. “Well, I just take them home and enjoy them with my own family.” “And likewise,” said the Buddha, “You have brought me a gift today that I don’t accept. You may take that gift home to your family.”

With patience, wit, and loving friendliness, the Buddha invites us to change how we think about the “gift” of angry words. If we respond to insults or angry words with mindfulness and loving friendliness, we are able to look closely at the whole situation. Perhaps that person did not know what he or she was saying. Perhaps the words were not meant to harm you. It may have been totally innocent or inadvertent. Perhaps it was your frame of mind at the time the words were spoken. Perhaps you did not hear the words clearly or misunderstood the context. It is also important to consider carefully what that person is saying. If you respond with anger, you will not hear the message behind the words. Perhaps that person is pointing out something you need to hear. We all encounter people who push our buttons. Without mindfulness and loving friendliness, we respond automatically with anger or resentment. With mindfulness, we can watch how our mind responds to certain words and actions.

Just as we do on the cushion, we can watch the arising of attachment and aversion. Mindfulness is like a safety net that cushions us against unwholesome actions. Mindfulness gives us time; time gives us choices. We don’t have to be swept away by our feelings. We can respond with wisdom rather than delusion.

Universal loving friendliness

Loving friendliness is not something we do sitting on a cushion in one place, thinking and thinking and thinking. We must let the power of loving friendliness shine through every encounter with others. Loving friendliness is the underlying principle behind all wholesome thoughts, words, and deeds. With lovingfriendliness, we recognize more clearly the needs of others and help them readily. With thoughts of loving friendliness we appreciate the success of others with warm feeling. We need loving friendliness in order to live and work with others in harmony. Loving friendliness protects us from the suffering caused by anger and jealousy. When we cultivate our loving friendliness, our compassion, our appreciative joy for others, and our equanimity, we not only make life more pleasant for those around us, our own lives become peaceful and happy.

The power of loving friendliness, like the radiance of the sun, is beyond measure. May all those who are imprisoned legally or illegally, all who are in police custody anywhere in the world meet with peace and happiness. May they be free from greed, anger, aversion, hatred, jealousy, and fear. Let their bodies and minds be filled with thoughts of loving friendliness. Let the peace and tranquillity of loving friendliness pervade their entire bodies and minds.

May all who are in hospitals suffering from numerous sicknesses meet with peace and happiness. May they be free from pain, afflictions, depression, disappointment, anxiety, and fear. Let these thoughts of loving friendliness embrace all of them, envelop them. Let their minds and bodies be filled with the thought of loving friendliness. May all mothers who are in pain delivering babies meet with peace and happiness. Let every drop of blood, every cell, every atom, every molecule of their entire bodies and minds be charged with these thoughts of friendliness.

May all single parents taking care of their children meet with peace and happiness. May they have the patience, courage, understanding, and determination to meet and overcome the inevitable difficulties, problems, and failures in life. May they be well, happy, and peaceful.

May all children abused by adults in numerous ways meet with peace and happiness. May they be filled with thoughts of loving friendliness, compassion, appreciative joy, and equanimity. May they be gentle. May they be relaxed. May their hearts become soft. May their words be pleasing to others. May they be free from fear, tension, anxiety, worry, and restlessness.

May all rulers be gentle, kind, generous, and compassionate. May they have understanding of the oppressed, the underprivileged, the discriminated against, and the poverty-stricken. May their hearts melt at the suffering of their unfortunate citizens. Let these thoughts of loving friendliness embrace them, envelop them. Let every cell, every drop of blood, every atom, every molecule of their entire bodies and minds be charged with thoughts of friendliness. Let the peace and tranquillity of loving friendliness pervade their entire being. May the oppressed and underprivileged, the poverty-stricken and those discriminated against, meet with peace and happiness. May they be free from pain, afflictions, depression, disappointment, anxiety, and fear. May all of them in all directions, all around the universe, be well, happy, and at peace. May they have the patience, courage, understanding, and determination to meet and overcome the inevitable difficulties, problems, and failures in life. May these thoughts of loving friendliness embrace all of them, envelop them. May their minds and bodies be filled with thoughts of loving friendliness.

May all beings everywhere of every shape and form, with two legs, four legs, many legs, or no legs, born or coming to birth, in this realm or the next, have happy minds. May no one deceive another nor despise anyone anywhere. May no one wish harm to another. Towards all living beings, may I cultivate a boundless heart, above, below, and all around, unobstructed without hatred or resentment. May all beings be released from suffering and attain perfect peace.

Loving friendliness goes beyond all boundaries of religion, culture, geography, language, and nationality. It is a universal and ancient law that binds all of us together—no matter what form we may take. Loving friendliness should be practised unconditionally. My enemy’s pain is my pain. His anger is my anger. His loving friendliness is my loving friendliness. If he is happy, I am happy.

If he is peaceful, I am peaceful. If he is healthy, I am healthy. Just as we all share suffering regardless of our differences, we should all share our loving friendliness with every person everywhere. No one nation can stand alone without the help and support of other nations, nor can any one person exist in isolation.

To survive, we need other living beings, beings who are bound to be different from us. That is simply the way things are. Because of the differences we have, the practice of loving friendliness is absolutely necessary. It is what ties all of us together. -Concluded.

****

The subject of this book

The subject of this book is Vipassana meditation practise. This is a meditation manual, a nuts-and-bolts, step-by-step guide to insight meditation. It is meant to be practical. It is meant for use.

There are many styles of meditation. Every major religious tradition has some sort of procedure that they call meditation, and the word is often very loosely used. Please understand that this volume deals exclusively with the Vipassana style of meditation, as taught and practised in South and Southeast Asian Buddhism. Vipassana is a Pali-language term often translated as “insight” meditation, since the purpose of this system is to give the meditator insight into the nature of reality and accurate understanding of how everything works.

Buddhism as a whole is quite different from the theological religions with which Westerners are most familiar. It is a direct entrance to a spiritual or divine realm, without assistance from deities or other “agents.” Its flavour is intensely clinical, much more akin to what we might call psychology than to what we would usually call religion. Buddhist practice is an ongoing investigation of reality, a microscopic examination of the very process of perception. Its intention is to pick apart the screen of lies and delusions through which we normally view the world, and thus to reveal the face of ultimate reality.

Vipassana meditation is an ancient and elegant technique for doing just that. Theravada (pronounced “terra vada”) Buddhism presents us with an effective system for exploring the deeper levels of the mind, down to the very root of consciousness itself. It also offers a considerable system of reverence and rituals,in which those techniques are contained. This beautiful tradition is the natural result of its 2,500-year development within the highly traditional cultures of South and Southeast Asia.

In this volume, we make every effort to separate the ornamental from the fundamental and to present only the plain truth. Those readers who are of a ritual bent may investigate the Theravada practice in other books, and will find there a vast wealth of customs and ceremony, a rich tradition full of beauty and significance. Those of a more pragmatic bent may use just the techniques themselves, applying them within whatever philosophical and emotional context they wish. The practice is the thing.

The distinction between Vipassana meditation and other styles of meditation is crucial, and needs to be fully understood. Buddhism addresses two major types of meditation; they are different mental skills or modes of functioning, different qualities of consciousness. In Pali, the original language of Theravada literature, they are called Vipassana and Samatha.

Vipassana can be translated as “insight,” a clear awareness of exactly what is happening as it happens. Samatha can be translated as “concentration” or “tranquillity,” and is a state in which the mind is focused only on one item, brought to rest, and not allowed to wander. When this is done, a deep calm pervades body and mind, a state of tranquillity that must be experienced to be understood. Most systems of meditation emphasize the Samatha component. The meditator focuses his or her mind on a certain item, such as a prayer, a chant, a candle flame, or a religious image, and excludes all other thoughts and perceptions from his or her consciousness. The result is a state of rapture, which lasts until the meditator ends the session of sitting. It is beautiful, delightful, meaningful, and alluring, but only temporary.

Vipassana meditation addresses the other component: insight. The Vipassana meditator uses concentration as a tool by which his or her awareness can chip away at the wall of illusion that blocks the living light of reality. It is a gradual process of ever-increasing awareness into the inner workings of reality itself. It takes years, but one day the meditator chisels through that wall and tumbles into the presence of light. The transformation is complete. It’s called liberation, and it’s permanent. Liberation is the goal of all Buddhist systems of practice. But the routes to the attainment of that end are quite diverse.

There are an enormous number of distinct sects within Buddhism. They divide into two broad streams of thought: Mahayana and Theravada. Mahayana Buddhism prevails throughout East Asia, shaping the cultures of China, Korea, Japan, Nepal, Tibet, and Vietnam. The most widely known of the Mahayana systems is Zen, practised mainly in Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and the United States. The Theravada system of practice prevails in South and Southeast Asia in the countries of Sri Lanka, Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia. This book deals with Theravada practice.

Traditional Theravada literature describes the techniques of both Samatha (concentration) and Vipassana (insight) meditation. There are forty different subjects of meditation described in the Pali literature. They are recommended as objects of concentration and subjects of investigation leading to insight. But this is a basic manual, and we will limit our discussion to the most fundamental of those recommended objects: breathing. This book is an introduction to the attainment of mindfulness through bare attention to, and clear comprehension of, the whole process of breathing. Using the breath as the primary focus of attention, the meditator applies participatory observation to the entirety of his or her own perceptual universe. The meditator learns to watch changes occurring in all physical experiences, feelings, and perceptions, and learns to study his or her own mental activities and the fluctuations in the character of consciousness itself. All of these changes are occurring perpetually and are present in every moment of our experiences.

Meditation is a living activity, an inherently experiential activity. It cannot be taught as a purely scholastic subject. The living heart of the process must come from the teacher’s own personal experience. Nevertheless, there is a vast fund of codified material on the subject, produced by some of the most intelligent and deeply illumined human beings ever to walk the earth. This literature is worthy of attention. Most of the points given in this book are drawn from the Tipitaka,which is the three-section compendium of the Buddha’s original teachings. The Tipitaka comprises of the Vinaya, the code of discipline for monks, nuns, and lay people; the Suttas, public discourses attributed to the Buddha; and the Abhidhamma, a set of deep psycho-philosophical teachings.

In the first century C.E., an eminent Buddhist scholar named Upatissa wrote the Vimuttimagga (The Path of Freedom), in which he summarised the Buddha’s teachings on meditation. In the fifth century C.E., another great Buddhist scholar, named Buddhaghosa, covered the same ground in a second scholastic thesis, the Visuddhimagga (The Path of Purification), which remains the standard text on meditation today.

This book offers you a foot in the door. It’s up to you to take the first few steps on the road to the discovery of who you are and what it all means. It is a journey worth taking.