Part 22

Continued from last week

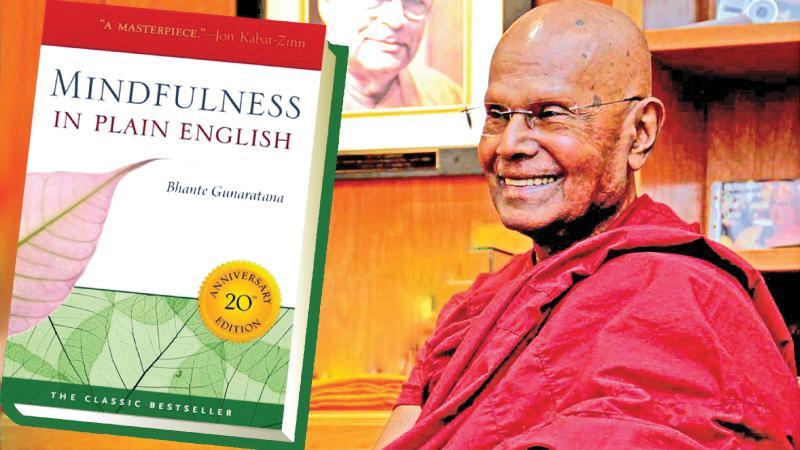

Extracted from renowned meditation guru Bhante Henepola Gunaratana’s Mindfulness in Plain English. The full text of the book will be carried in the Sunday Observer in installments.

Different objects reflect the sun’s energy differently. Similarly, people differ in their ability to express loving friendliness. Some people seem naturally warmhearted, while others are more reserved and reluctant to open their hearts. Some people struggle to cultivate metta; others cultivate it without difficulty. But there is no one who is totally devoid of loving friendliness. We are all born with the instinct for metta. We can see it even in young babies who smile readily at the sight of another human face, any human face at all. Sadly, many people have no idea how much loving friendliness they have. Their innate capacity for loving friendliness may be buried under a heap of hatred, anger, and resentment accumulated through a lifetime—perhaps many lifetimes—of unwholesome thoughts and actions. But all of us can cultivate our heart, no matter what. We can nourish the seeds of loving friendliness until the force of loving friendliness blossoms in all our endeavors.

In the Buddha’s time, there was a man named Angulimala; this man was, to use the language of today, a serial killer, a mass murderer. He was so wretched that he wore around his neck a garland of fingers taken from the people he had slaughtered, and he planned to make the Buddha his thousandth victim. In spite of Angulimala’s reputation and his gruesome appearance, the Buddha nonetheless could see his capacity for loving friendliness. Thus, out of love and compassion—his own loving friendliness—the Buddha taught the Dhamma to this villainous murderer. As a result of the Buddha’s teaching, Angulimala threw away his sword and surrendered to the Buddha, joining the followers of the Buddha and becoming ordained.

As it turned out, Angulimala started his vicious killing spree many years earlier because a man whom Angulimala regarded as his teacher had (for unwholesome reasons of his own) directed him to do so. Angulimala was not by nature a cruel person, nor was he an evil person. In fact, he had been a kind boy.

In his heart, there was loving friendliness, gentleness, and compassion. As soon as he became a bhikkhu, his true nature was revealed, and not long after his ordination, he became enlightened.

The story of Angulimala shows us that sometimes people can appear very cruel and wicked, yet we must realise they are not that way by nature.

Unwholesome acts

Circumstances in their lives make them act in unwholesome ways. In

Angulimala’s case, he became a murderer because of his devotion to his teacher. For every one of us, not just violent criminals, there are countless causes and conditions—both wholesome and unwholesome—that make us act as we do.

In addition to the meditation offered earlier in this book, I’d like to offer another way to practice loving friendliness. Again, you start out in this meditation by banishing thoughts of self-hatred and condemnation. At the beginning of a meditation session, say the following sentences to yourself. And again, really feel the intention:

May my mind be filled with the thoughts of loving friendliness, compassion,appreciative joy, and equanimity.

May I be generous.

May I be gentle.

May I be relaxed.

May I be happy and peaceful.

May I be healthy.

May my heart become soft.

May my words be pleasing to others.

May my actions be kind.

May all that I see, hear, smell, taste, touch, and think help me to cultivate loving friendliness, compassion, appreciative joy, and equanimity.

May all these experiences help me to cultivate thoughts of generosity and gentleness.

May they all help me to relax.

May they inspire friendly behavior.

May these experiences be a source of peace and happiness.

May they help me be free from fear, tension, anxiety, worry, and restlessness.

No matter where I go in the world, in any direction, may I greet people with happiness, peace, and friendliness.

May I be protected in all directions from greed, anger, aversion, hatred, jealousy, and fear.

When we cultivate loving friendliness in ourselves, we learn to see that others have this kind, gentle nature—however well hidden it might be. Sometimes we have to dig very deep to find it, other times it might be nearer to the surface.

Seeing through the dirt

The Buddha told the story of a bhikkhu who finds a filthy piece of cloth on the road. The rag is so nasty, at first the bhikkhu does not even want to touch it. He kicks it with his foot to knock off some of the dirt. Disgusted, he gingerly picks it up with two fingers, holding it away from himself with contempt. Yet even as the monk does this, he sees potential in that scrap of dirty cloth, and takes it home and washes it—over and over and over. Eventually, the wash water runs clean, and from underneath the filth and grime, a useful piece of material is revealed. The bhikkhu sees that if he collects enough pieces, he could, perhaps, make this rag into part of a robe.

Likewise, because of a person’s nasty words, that person may seem totally worthless; it may be impossible to see that person’s potential for loving friendliness. But this is where the practice of Skillful Effort comes in.

Underneath such a person’s rough exterior, you may find the warm, radiant jewel that is the person’s true nature.

A person may use very harsh words for others, yet sometimes still act with compassion and kindness. In spite of her words, her deeds may be good. The Buddha compared this kind of person to a pond covered by moss. In order to use that water, you must brush the moss aside. Similarly, we sometimes need to ignore a person’s superficial weaknesses to find her good heart.

Cruel words and unkind action

But what if a person’s words are cruel and her actions too are unkind? Is she rotten through and through? Even a person like this may have a pure heart. Imagine you have been walking through a desert. You have no water with you, and there is no water anywhere around. You are hot and tired. With every step, you become thirstier and thirstier. You are desperate for water. Then you come across a cow’s footprint. There is water in the footprint, but not much because the footprint is not very deep. If you try to scoop up the water with your hand, it will become very muddy. You are so thirsty, you kneel down and bend over.

Very slowly, you bring your mouth to the water and sip it, very carefully so as not to disturb the mud. Even though there is dirt all around, the little bit of water is still clear. You can quench your thirst. With similar effort, we can find a good heart even in a person who seems totally without redemption.

Very slowly, you bring your mouth to the water and sip it, very carefully so as not to disturb the mud. Even though there is dirt all around, the little bit of water is still clear. You can quench your thirst. With similar effort, we can find a good heart even in a person who seems totally without redemption.

The meditation centre where I most often teach is in the hills of the West Virginia countryside. When we first opened our centre, there was a man down the road who was very unfriendly. I take a long walk every day, and, whenever I saw this man, I would wave to him. He would just frown at me and look away.

Even so, I would always wave and think kindly of him, sending him metta. I was not phased by his attitude; I never gave up on him. Whenever I saw him, I waved. After about a year, his behaviour changed. He stopped frowning. I felt wonderful. The practice of loving friendliness was beginning to bear fruit.

After another year, when I passed him on my walk, something miraculous happened. He drove past me and lifted one finger off the steering wheel. Again, I thought, “Oh, this is wonderful! Loving friendliness is working.” And yet another year passed as, day after day, I would wave to him and wish him well.

The third year, he lifted two fingers in my direction. Then the next year, he lifted all four fingers off the wheel. More time passed. I was walking down the road as he turned into his driveway. He took his hand completely off the steering wheel, stuck it out the window, and waved back to me.

One day, not long after that, I saw this man parked on the side of one of the forest roads. He was sitting in the driver’s seat smoking a cigarette. I went over to him and we started talking. First we chatted just about the weather and then, little by little, his story unfolded: It turns out that, several years ago, he had been in a terrible accident—a tree had fallen on his truck. Almost every bone in his body had been broken, and he was left in a coma for some time.

When I first started seeing him on the road, he was only beginning to recover. It was not because he was a mean person that he did not wave back to me; he did not wave back because he could not move all his fingers! Had I given up on him, I would never have known how good this man is. One day, when I had been away on a trip, he actually came by our center looking for me. He was worried because he hadn’t seen me walking in a while. Now we are friends.

Practising loving friendliness

The Buddha said, “By surveying the entire world with my mind, I have not come across anyone who loves others more than himself. Therefore one who loves himself should cultivate this loving friendliness.” Cultivate loving friendliness towards yourself first, with the intention of sharing your kind thoughts with others. Develop this feeling. Be full of kindness toward yourself. Accept yourself just as you are. Make peace with your shortcomings. Embrace even your weaknesses. Be gentle and forgiving with yourself as you are at this very moment. If thoughts arise as to how you should be such and such a way, let them go. Establish fully the depth of these feelings of goodwill and kindness. Let the power of loving friendliness saturate your entire body and mind. Relax in its warmth and radiance. Expend this feeling to your loved ones, to people you don’t know or feel neutrally about—and even to your adversaries!

Let each and every one of us imagine that our minds are free from greed,anger, aversion, jealousy, and fear. Let the thought of loving friendliness embrace us and envelop us. Let every cell, every drop of blood, every atom, every molecule of our entire bodies and minds be charged with the thought of friendliness. Let us relax our bodies. Let us relax our minds. Let our minds and bodies be filled with the thought of loving friendliness. Let the peace and tranquillity of loving friendliness pervade our entire being. May all beings in all directions, all around the universe, have good hearts.

Let them be happy, let them have good fortune, let them be kind, let them have good and caring friends. May all beings everywhere be filled with the feeling of loving friendliness—abundant, exalted, and measureless. May they be free from enmity, free from affliction and anxiety. May they live happily.

Just as we walk or run or swim to strengthen our bodies, the practice of loving friendliness on a regular basis strengthens our hearts. At first it may seem as if you are only going through the motions. But by associating with thoughts of metta over and over, it becomes a habit, a good habit. In time, your heart grows stronger, and the response of loving friendliness becomes automatic. As our hearts become stronger, even towards difficult people we can think kind and loving thoughts.

May my adversaries be well, happy, and peaceful. May no harm come to them, may no difficulty come to them, may no pain come to them. May they always meet with success.

“Success?” some people ask. “How can we wish our adversaries success?

What if they’re trying to kill me?” When we wish success for our adversaries, we don’t mean worldly success or success in doing something immoral or unethical; we mean success in the spiritual realm. Our adversaries are clearly not successful spiritually; if they were successful spiritually, they would not be acting in a way that causes us harm.

Whenever we say of our adversaries, “May they be successful,” we mean:

“May my enemies be free from anger, greed, and jealousy. May they have peace, comfort, and happiness.” Why is somebody cruel or unkind? Perhaps that person was brought up under unfortunate circumstances. Perhaps there are situations in that person’s life we don’t know about that cause him or her to act cruelly. The Buddha asked us to think of such people the same way we would if someone were suffering from a terrible illness. Do we get angry or upset with people who are ill? Or do we have sympathy and compassion for them? Perhaps even more than our loved ones, our adversaries deserve our kindness, for their suffering is so much greater. For these reasons, without any reservation, we should cultivate kind thoughts about them. We include them in our hearts just as we would those dearest to us.

May all those who have harmed us be free from greed, anger, aversion, hatred, jealousy, and fear. Let these thoughts of loving friendliness embrace them, envelop them. Let every cell, every drop of blood, every atom, every molecule of their entire bodies and minds be charged with thoughts of friendliness. Let them relax their bodies. Let them relax their minds. Let the peace and tranquillity pervade their entire being.

Practising loving friendliness can change our habitual negative thought patterns and reinforce positive ones. When we practise metta meditation, our minds will become filled with peace and happiness. We will be relaxed. We gain concentration. When our mind becomes calm and peaceful, our hatred, anger, and resentment fade away. But loving friendliness is not limited to our thoughts.We must manifest it in our words and our actions. We cannot cultivate loving friendliness in isolation from the world.

You can start by thinking kind thoughts about everyone you have contact with every day. If you have mindfulness, you can do this every waking minute with everyone you deal with. Whenever you see someone, consider that, like yourself, that person wants happiness and wants to avoid suffering. We all feel that way.

All beings feel that way. Even the tiniest insect recoils from harm. When we recognise that common ground, we see how closely we are all connected. The woman behind the checkout counter, the man who passes you on the expressway, the young couple walking across the street, the old man in the park feeding the birds. Whenever you see another being, any being, keep this in mind. Wish for them happiness, peace, and well-being. It is a practice that can change your life and the lives of those around you.

At first, you may experience resistance to this practice. Perhaps the practice seems forced. Perhaps you feel unable to bring yourself to feel these kinds of thoughts. Because of experiences in your own life, it may be easier to feel loving friendliness for some people and more difficult for others. Children, for example, often bring out our feelings of loving friendliness quite naturally; while with others, it may be more difficult. Watch the habits in your mind. Learn to recognise your negative emotions and start to break them down. With mindfulness, little by little you can change your responses. Does sending someone thoughts of loving friendliness actually change the other person? Can practising loving friendliness change the world? When you are sending loving friendliness to people who are far away or people you may not even know, of course, it is not possible to know the effect. But you can notice the effect that practicing loving friendliness has on your own peace of mind. What is important is the sincerity of your own wish for the happiness of others. Truly, the effect is immediate. The only way to find this out for yourself is to try it.

Practising metta does not mean that we ignore the unwholesome actions of others. It simply means that we respond to such actions in an appropriate way.

There was a prince named Abharaja Kumara. One day he went to the Buddha and asked whether the Buddha was ever harsh to others. At this time the prince had his little child on his lap. “Suppose, Prince, this little child of yours were to put a piece of wood in his mouth, what would you do?” asked the Buddha. “If he put a piece of wood in his mouth, I would hold the child very tightly between my legs and put my crooked index finger in his mouth. Though he might be crying and struggling in discomfort, I would pull the piece of wood out even if he bleeds,” said the prince. “Why would you do that?”

“Because I love my child. I want to save his life,” was his reply.

“Similarly, Prince, sometimes I have to be harsh on my disciples not out of cruelty, but out of love for them,” said the Buddha. Loving friendliness, not anger, motivated his actions.

The Buddha provided us with five very basic tools for dealing with others in a kindhearted way. These tools are the five precepts. Some people think of morality as restrictions on freedom, but in fact, these precepts liberate us. They free us from the suffering we cause ourselves and others when we act unkindly. These guidelines train us to protect others from harm; and, by protecting others, we protect ourselves. The precepts caution us to abstain from taking life, from stealing, from sexual misconduct, from speaking falsely or harshly, and from using intoxicants that cause us to act in an unmindful way.

Developing mindfulness through the practice of meditation also helps us relate to others with loving friendliness. On the cushion, we watch our minds as liking and disliking arise. We teach ourselves to relax our mind when such thoughts arise. We learn to see attachment and aversion as momentary states, and we learn to let them go. Meditation helps us look at the world in a new light and gives us a way out. The deeper we go in our practice, the more skills we develop.

To be continued