Part 21

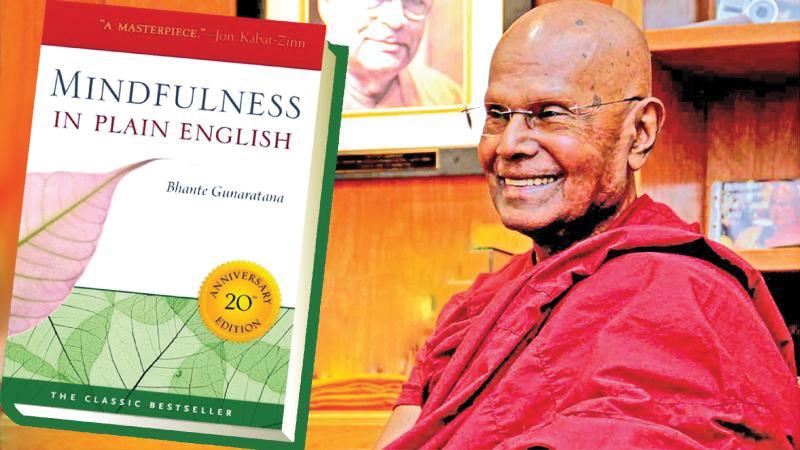

Extracted from renowned meditation guru Bhante Henepola Gunaratana’s Mindfulness in Plain English. The full text of the book will be carried in the Sunday Observer in installments.

Continued from last week

You can expect certain benefits from your meditation. The initial ones are practical things; the later stages are profoundly transcendental. They run together from the simple to the sublime. We will set forth some of them here. Your own practice can show you the truth. Your own experience is all that counts.

Those things that we called hindrances or defilements are more than just unpleasant mental habits. They are the primary manifestations of the ego process itself. The ego sense itself is essentially a feeling of separation—a perception of distance between that which we call me and that which we call other. This perception is held in place only if it is constantly exercised, and the hindrances constitute that exercise.

Greed and lust are attempts to “get some of that” for me; hatred and aversion are attempts to place greater distance between “me and that.” All the defilements depend upon the perception of a barrier between self and other, and all of them foster this perception every time they are exercised. Mindfulness perceives things deeply and with great clarity. It brings our attention to the root of the defilements and lays bare their mechanism. It sees their fruits and their effects upon us. It cannot be fooled. Once you have clearly seen what greed really is and what it really does to you and to others, you just naturally cease to engage in it.

When a child burns her hand on a hot oven, you don’t have to tell her to pull it back; she does it naturally, without conscious thought and without decision. There is a reflex action built into the nervous system for just that purpose, and it works faster than thought. By the time the child perceives the sensation of heat and begins to cry, the hand has already been jerked back from the source of pain.

Mindfulness works in very much the same way: it is wordless, spontaneous, and utterly efficient. Clear mindfulness inhibits the growth of hindrances; continuous mindfulness extinguishes them. Thus, as genuine mindfulness is built up, the walls of the ego itself are broken down, craving diminishes, defensiveness and rigidity lessen, you become more open, accepting, and flexible. You learn to share your loving friendliness.

Traditionally, Buddhists are reluctant to talk about the ultimate nature of human beings. But those who are willing to make descriptive statements at all usually say that our ultimate essence or Buddha nature is pure, holy, and inherently good. The only reason that human beings appear otherwise is that their experience of that ultimate essence has been hindered; it has been blocked like water behind a dam. The hindrances are the bricks of which that dam is built. As mindfulness dissolves the bricks, holes are punched in the dam, and compassion and sympathetic joy come flooding forward. As meditative mindfulness develops, your whole experience of life changes. Your experience of being alive, the very sensation of being conscious becomes lucid and precise, no longer just an unnoticed background for your preoccupations.

It becomes a thing consistently perceived. Each passing moment stands out as itself; the moments no longer blend together in an unnoticed blur. Nothing is glossed over or taken for granted, no experiences labeled as merely “ordinary.” Everything looks bright and special.

You refrain from categorising your experiences into mental pigeonholes. Descriptions and interpretations are chucked aside, and each moment of time is allowed to speak for itself. You actually listen to what it has to say, and you listen as if it were being heard for the very first time. When your meditation becomes really powerful, it also becomes constant. You consistently observe with bare attention both the breath and every mental phenomenon. You feel increasingly stable, increasingly moored in the stark and simple experience of moment-to-moment existence.

Once your mind is free from thought, it becomes clearly wakeful and at rest in an utterly simple awareness. This awareness cannot be described adequately.

Words are not enough. It can only be experienced. Breath ceases to be just breath; it is no longer limited to the static and familiar concept you once held. You no longer see it as a succession of just inhalations and exhalations, an insignificant monotonous experience. Breath becomes a living, changing process, something alive and fascinating. It is no longer something that takes place in time; it is perceived as the present moment itself. Time is seen as a concept, not an experienced reality.

This is a simplified, rudimentary awareness that is stripped of all extraneous detail. It is grounded in a living flow of the present, and it is marked by a pronounced sense of reality. You know absolutely that this is real, more real than anything you have ever experienced. Once you have gained this perception with absolute certainty, you have a fresh vantage point, a new criterion against which to gauge all of your experience. After this perception, you see clearly those moments when you are participating in bare phenomena alone, and those moments when you are disturbing phenomena with mental attitudes. You watch yourself twisting reality with mental comments, with stale images and personal opinions.

Increasingly sensitive

You know what you are doing, when you are doing it. You become increasingly sensitive to the ways in which you miss the true reality, and you gravitate towards the simple objective perspective that does not add to or subtract from what is. You become a very perceptive individual. From this vantage point, all is seen with clarity. The innumerable activities of mind and body stand out in glaring detail. You mindfully observe the incessant rise and fall of breath; you watch an endless stream of bodily sensations and movements; you scan the rapid succession of thoughts and feelings, and you sense the rhythm that echoes from the steady march of time. And in the midst of all this ceaseless movement, there is no watcher, there is only watching.

In this state of perception, nothing remains the same for two consecutive moments. Everything is seen to be in constant transformation. All things are born, all things grow old and die. There are no exceptions. You awaken to the unceasing changes of your own life. You look around and see everything in flux, everything, everything, everything. It is all rising and falling, intensifying and diminishing, coming into existence and passing away. All of life, every bit of it from the infinitesimal to the Pacific Ocean, is in motion constantly. You perceive the universe as a great flowing river of experience. Your most cherished possessions are slipping away, and so is your very life. Yet this impermanence is no reason for grief. You stand there transfixed, staring at this incessant activity, and your response is wondrous joy. It’s all moving, dancing, and full of life.

As you continue to observe these changes and you see how it all fits together, you become aware of the intimate connectedness of all mental, sensory, and affective phenomena. You watch one thought leading to another, you see destruction giving rise to emotional reactions and feelings giving rise to more thoughts. Actions, thoughts, feelings, desires—you see all of them intimately linked together in a delicate fabric of cause and effect. You watch pleasurable experiences arise and fall, and you see that they never last; you watch pain come uninvited and you watch yourself anxiously struggling to throw it off; you see yourself fail. It all happens over and over while you stand back quietly and just watch it all work.

Out of this living laboratory itself comes an inner and unassailable conclusion.

You see that your life is marked by disappointment and frustration, and you clearly see the source. These reactions arise out of your own inability to get what you want, your fear of losing what you have already gained, and your habit of never being satisfied with what you have. These are no longer theoretical concepts—you have seen these things for yourself, and you know that they are real. You perceive your own fear, your own basic insecurity in the face of life and death.

It is a profound tension that goes all the way down to the root of thought and makes all of life a struggle. You watch yourself anxiously groping about, fearfully grasping after solid, trustworthy ground. You see yourself endlessly grasping for something, anything, to hold onto in the midst of all these shifting sands, and you see that there is nothing to hold onto, nothing that doesn’t change.

You see the pain of loss and grief, you watch yourself being forced to adjust to painful developments day after day in your own ordinary existence. You witness the tensions and conflicts inherent in the very process of everyday living, and you see how superficial most of your concerns really are. You watch the progress of pain, sickness, old age, and death. You learn to marvel that all these horrible things are not fearful at all. They are simply reality.

Through this intensive study of the negative aspects of your existence, you become deeply acquainted with dukkha, the unsatisfactory nature of all existence. You begin to perceive dukkha at all levels of our human life, from the obvious down to the most subtle. You see the way suffering inevitably follows in the wake of clinging, as soon as you grasp anything, pain inevitably follows.

Once you become fully acquainted with the whole dynamic of desire, you become sensitised to it. You see where it rises, when it rises, and how it affects you. You watch it operate over and over, manifesting through every sense channel, taking control of the mind and making consciousness its slave.

In the midst of every pleasant experience, you watch your own craving and clinging take place. In the midst of unpleasant experiences, you watch a very powerful resistance take hold. You do not block these phenomena, you just watch them; you see them as the very stuff of human thought. You search for that thing you call “me,” but what you find is a physical body and how you have identified your sense of yourself with that bag of skin and bones. You search further, and you find all manner of mental phenomena, such as emotions, thought patterns, and opinions, and see how you identify the sense of yourself with each of them. You watch yourself becoming possessive, protective, and defensive over these pitiful things, and you see how crazy that is.

You rummage furiously among these various items, constantly searching for yourself—physical matter, bodily sensations, feelings, and emotions—it all keeps whirling round and round as you root through it, peering into every nook and cranny, endlessly hunting for “me.”

You find nothing. In all that collection of mental hardware in this endless stream of ever-shifting experience, all you can find is innumerable impersonal processes that have been caused and conditioned by previous processes. There is no static self to be found; it is all process. You find thoughts but no thinker, you find emotions and desires, but nobody doing them. The house itself is empty.

There is nobody home.

Your whole view of self changes at this point. You begin to look upon yourself as if you were a newspaper photograph. When viewed with the naked eyes, the photograph you see is a definite image. When viewed through a magnifying glass, it all breaks down into an intricate configuration of dots. Similarly, under the penetrating gaze of mindfulness, the feeling of a self, an “I” or “being” anything, loses its solidity and dissolves.

There comes a point in insight meditation where the three characteristics of existence—impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and selflessness—come rushing home with concept-searing force. You vividly experience the impermanence of life, the suffering nature of human existence, and the truth of no-self. You experience these things so graphically that you suddenly awake to the utter futility of craving, grasping, and resistance.

In the clarity and purity of this profound moment, our consciousness is transformed. The entity of self evaporates. All that is left is an infinity of interrelated nonpersonal phenomena, which are conditioned and ever-changing. Craving is extinguished and a great burden is lifted. There remains only an effortless flow, without a trace of resistance or tension. There remains only peace, and blessed nibbana, the uncreated, is realized.

Afterword: The Power of Loving Friendliness THE TOOLS of mindfulness discussed in this book, if you choose to take advantage of them, can surely transform your every experience. In the afterword to the this new edition, I’d like to take some time to emphasize the importance of another aspect of the Buddha’s path that goes hand in hand with mindfulness: metta, or loving friendliness. Without loving friendliness, our practice of mindfulness will never successfully break through our craving and rigid sense of self. Mindfulness, in turn, is a necessary basis for developing loving friendliness.

The two are always developed together. In the decade since this volume first appeared, much has happened in the world to increase people’s feelings of insecurity and fear. In this troubled climate, the importance of cultivating a deep sense of loving friendliness is especially crucial for our well-being, and it is the best hope for the future of the world. The concern for others embodied in loving friendliness is at the heart of the promise of the Buddha—you can see it everywhere in his teachings and in the way he lived his life.

Each of us is born with the capacity for loving friendliness. Yet only in a calm mind, a mind free from anger, greed, and jealousy, can the seeds of loving friendliness develop; only from the fertile ground of a peaceful mind can loving friendliness flower. We must nurture the seeds of loving friendliness in ourselves and in others, help them take root and mature.

I travel all over the world teaching the Dhamma, and consequently I spend a lot of time in airports. One day I was in Gatwick airport near London waiting for a flight. I had quite a bit of time, but for me having time on my hands is not a problem. In fact, it is a pleasure, since it means more opportunity for meditation! So there I was, sitting cross-legged on one of the airport benches with my eyes closed, while all around me people were coming and going, rushing to and from their flights. When meditating in situations like this, I fill my mind with thoughts of loving friendliness and compassion for everyone everywhere. With every breath, with every pulse, with every heartbeat, I try to allow my entire being to become permeated with the glow of loving friendliness.

In that busy airport, absorbed in feelings of metta, I was paying no attention to the hustle and bustle around me, but soon I had the sensation that someone was sitting quite close to me on the bench. I didn’t open my eyes but merely kept on with my meditation, radiating loving friendliness. Then I felt two tiny, tender hands reaching around my neck, and I slowly opened my eyes and discovered a very beautiful child, a little girl perhaps two years old.

This little one, with bright blue eyes and a head covered in downy blond curls, had put her arms around me and was hugging me. I had seen this sweet child as I was people watching; she had had her hand grasped around her mother’s little finger. Apparently, the little girl had loosened herself from her mother’s hand and run over to me.

I looked over and saw that her mother had chased after her. Seeing her little girl with her arms around my neck, the mother asked me, “Please bless my little girl and let her go.” I did not know what language the child spoke, but I said to her in English, “Please go. Your mother has lots of kisses for you, lots of hugs, lots of toys, and lots of sweets. I have none of those things. Please go.” The child hung on to my neck and would not let go. Again, the mother folded her palms together and pleaded with me in a very kindly tone, “Please, Sir, give her your blessing and let her go.”

By this time, other people in the airport were beginning to notice. They must have thought that I knew this child, that perhaps she was related to me somehow.

Surely they thought there was some strong bond between us. But I had never before that day seen this lovely little child. I did not even know what language she spoke. Again, I urged her, “Please go. You and your mother have a plane to catch. You are late. Your mother has all your toys and candy. I have nothing. Please go.” But the little girl would not budge. She clung to me harder and harder. The mother then very gently took the little girl’s hands off my neck and asked me to bless her. “You are a very good little girl,” I said. “Your mother loves you very much. Hurry. You might miss your plane. Please go.” But still the little girl would not go. She was crying and crying. Finally the mother carefully snatched her up. The toddler was kicking and screaming. She was trying to get loose and come back to me. But this time the mother managed to carry her off to the plane. The last I saw of her she was still struggling to get loose and run back to me.

Maybe because of my robes, this little girl thought I was a Santa Claus or some kind of fairytale figure. But there is another possibility: At the time I was sitting on that bench, I was practising metta, sending out thoughts of loving friendliness with every breath. Perhaps this little child felt this; children are extremely sensitive in these ways, their psyches absorb whatever feelings are around them. When you are angry, they feel those vibrations; and when you are full of love and compassion, they feel that too. This little girl may have been drawn to me by the feelings of loving friendliness she felt. There was a bond between us—the bond of loving friendliness.

The four sublime states

Loving friendliness works miracles. We have the capacity to act with loving friendliness. We may not even know we have this quality in ourselves, but the power of loving friendliness is inside us all. Loving friendliness is one of the four sublime states defined by the Buddha, along with compassion, appreciative joy, and equanimity. All four states are interrelated; we cannot develop one without the other.

One way to understand them is to think of different stages of parenthood.

When a young woman finds out she is going to have a child, she feels a tremendous outpouring of love for the baby she will bear. She will do everything she can to protect the infant growing inside her. She will make every effort to make sure the baby is well and healthy. She is full of loving, hopeful thoughts for the child. Like metta, the feeling a new mother has for her infant is limitless and all-embracing; and, like metta, it does not depend on actions or behaviour of the one receiving our thoughts of loving friendliness.

As the infant grows older and starts to explore his world, the parents develop compassion. Every time the child scrapes his knee, falls down, or bumps his head, the parent feels the child’s pain. Some parents even say that when their child feels pain, it is as if they themselves were being hurt. There is no pity in this feeling; pity puts distance between others and ourselves. Compassion leads us to appropriate action; and the appropriate, compassionate action is just the pure, heartfelt hope that the pain stop and the child not suffer.

As time passes, the child heads off to school. Parents watch as the youngster makes friends, does well in school, sports, and other activities. Maybe the child does well on a spelling test, makes the baseball team, or gets elected class president. The parents are not jealous or resentful of their child’s success but are full of happiness for the child. This is appreciative joy. Thinking of how we would feel for our own child, we can feel this for others. Even when we think of others whose success exceeds our own, we can appreciate their achievement and rejoice in their happiness.

To continue in our example: Eventually, after many years, the child grows up.

He finishes school and goes out on his own; perhaps he marries and starts a family. Now it is time for the parents to practise equanimity. Clearly, what the parents feel for the child is not indifference. It is an appreciation that they have done all that they could do for the child. They recognise their limitations. Of course the parents continue caring for and respecting their child, but they do so with awareness that they no longer steer the outcome of their child’s life. This is the practice of equanimity.

The ultimate goal of our practice of meditation is the cultivation of these four sublime states of loving friendliness, compassion, appreciative joy, and equanimity.

The word metta comes from another Pali word, mitra, which means “friend.” That is why I prefer to use the phrase “loving friendliness” as a translation of metta, rather than “loving kindness.” The Sanskrit word mitra also refers to the sun at the centre of our solar system that makes all life possible. Just as the sun’s rays provide energy for all living things, the warmth and radiance of metta flows in the heart of all living beings.

To be continued