In a devastating new book, the son of one of Anne’s confidantes reveals why he thinks he’s found the shocking answer.

When SS officer Karl Silberbauer and his two Dutch Nazi henchmen marched into the warehouse of Opekta Ltd in Amsterdam on August 4, 1944, and shouted, ‘Where are the Jews’?, 25-year-old Bep Voskuijl knew the game was up.

As she watched those men pulling out the movable bookcase and walking up the staircase hidden behind it, to round up Anne Frank and the seven other terrified Jews in the secret annexe, Bep fell to her knees and prayed.

Every day for 760 days, working as a secretary in Otto Frank’s warehouse, Bep, along with her colleague Miep Gies and a tiny number of trusted helpers, had kept the annexe a total secret.

The only other person in Bep’s family who knew about it was her father, who’d also worked at Opteka until he had to leave due to cancer. It was he who’d built that bookcase to hide what would become known as ‘the helpers’ staircase’.

With great bravery, aware of reprisals meted out to anyone discovered aiding or hiding Jews, Bep had helped the Frank family and their co-hiders for more than two years, sourcing and bringing them food, and keeping them cheerful.

With great bravery, aware of reprisals meted out to anyone discovered aiding or hiding Jews, Bep had helped the Frank family and their co-hiders for more than two years, sourcing and bringing them food, and keeping them cheerful.

Bep and the teenage Anne had become particularly fond of each other. Once, Anne had begged Bep to stay for a sleepover in the annexe, which Bep did, squeezing onto the strip of floor next to Anne’s bed.

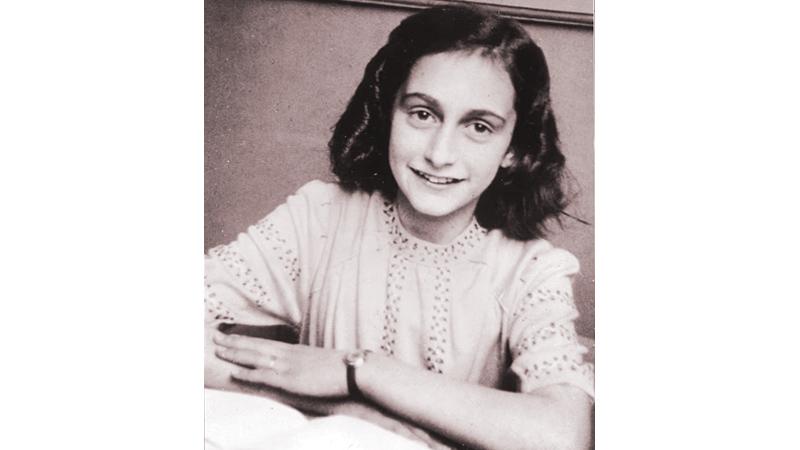

The shock of that August morning was terrible. Of the eight hiding in the annexe, only one, Otto, would survive the ensuing horrors of forced slave labour, Auschwitz and — for Anne and her sister Margot — starvation and typhus at Bergen-Belsen.

Bep and Miep entered the deserted Annex a few days after the family had gone. It still smelled of the boiled kidney beans they’d had for breakfast on their final morning and the table was laid for mid-morning coffee.

That glimpse brings home the suddenness of the catastrophe which befell them just before elevenses on the 761st day.

Ransacked annexe

The story of Anne’s diary, and other loose sheets of paper covered in her handwriting, being discovered on the floor of the ransacked annexe by Miep and Bep, and Miep keeping it all safe until Otto returned in 1945, is well-known.

In this compelling new book, Bep’s son, Joop van Wijk-Voskuijl, with the help of fellow-sleuth Jeroen De Bruyn, tells the much less-well-known story of Joop’s deeply troubled and haunted mother.

The secret annexe was a taboo subject in his family while he was growing up after the war— and he wonders why.

Shouldn’t Bep, his heroic mother, have welcomed the halo and semi-celebrity of having been someone who had helped the Frank family during those dark years of Nazi occupation, even though the end was tragic for those people?

Instead, he writes: ‘If my mother started even thinking about the secret annexe, she would get a migraine, slip into a depression and spend much of the next day in bed.’

Was this due to a guilty conscience? Was she nursing a secret she couldn’t bring herself to divulge?

‘Who betrayed Anne Frank?’ is an abiding mystery of the Holocaust. Last year, Canadian journalist Rosemary Sullivan concluded, at the end of a long ‘cold case’ investigation, that the betrayer was a Jewish notary, Arnold van den Bergh, who’d told on the Franks to save his own family.

Scholars were quick to tear apart her theory. Joop is careful here not to come to any certain conclusion, or to claim to be ‘cracking’ a ‘cold case’. We may never know the truth, he writes.

His mother Bep was the eldest of seven siblings in an impoverished and unhappy family. One of her younger sisters, Nelly (born in 1923), was a keen Nazi.

Early in the war years, Joop’s Aunt Nelly took a job as a servant for a wealthy family who entertained German officers, and she fell in love with a Nazi called Siegfried.

She followed him back to Austria, found out he was secretly engaged to another woman and returned heartbroken to Amsterdam — but, importantly, her return was after the raid on the secret annexe. At least, that was what Joop had always been led to believe.

Then, writes Joop, in March 2010, ‘everything changed’ and ‘the scales fell from my eyes’.

Jeroen had come across a typescript of some lengthy, never-before-published passages from Anne’s diary, in which she mentioned Nelly as Bep’s sister, who ‘probably kept a photo of the Fuhrer in her wallet’.

It turned out that Nelly had, in fact, returned to Amsterdam in May 1944, three months before the betrayal.

Bep’s fiance

Joop and Jeroen then visited an old man called Bertus, who’d been Bep’s fiance during the war years. Bertus recalled a row at the Voskuijl dinner table, when Nelly had stormed out of the room after yelling at Bep: ‘Just go to your Jews!’

So Nelly suspected the truth. She was jealous of the bond between Bep and their father, Johan, who liked to chat quietly together in a separate room most evenings.

Nelly guessed they were keeping a secret from her. So, was it she who informed on the hidden Jews as a form of revenge? Silberbauer did mention, when he was eventually tracked down by Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal and questioned in 1963, that he’d been told that the informant on the telephone ‘had had the voice of a young woman’.

And why was Bep spared the ordeal of interrogation by the Nazis after the raid? Gies was subjected to harsh interrogation, and the other two helpers, Victor Kugler and Jo Kleiman, were arrested and imprisoned for helping the Franks. Could it be that Nelly had betrayed the Jews to the police on the condition they did not arrest or interrogate her sister Bep?

Another sister, Diny, recalled that, on the evening after the raid, their father kicked and hit Nelly, violently beating her over the head.

Three times, over the decades, Joop dared to ask his Aunt Nelly what exactly had happened to her during the war. Her eyes fluttered, he writes. She nearly fainted; once, she actually had a seizure. ‘I’ve never been the same since Father kicked me over the head,’ she said.

She went on to live a normal life, working as a cinema usher and a church sexton. She died in 2001 after falling down the stairs.

Bep was a deeply unhappy woman for the rest of her life, and it was not easy to be her son. She married a drunken, unkind man.

Once, Joop came home to find Bep in the bathroom having taken an overdose, and saved her life. She swore him to secrecy. She and her husband went on to have one last child, named Anne, after Anne Frank.

One day in 1960, when pregnant with Anne, Bep quietly told her younger sister: ‘Rumour has it that Nelly is the betrayer. As a matter of fact, we think it is true, but things should be proven first.’

Until that proof comes, we can only use conjecture. But that cinema usher may well have been guilty of one of the Holocaust’s darkest secrets.