Joan Didion, one of America’s leading modern day writers,especially on essays, memoirs, novels and screenplays, died recently at the age of 87. The cause for her death was complications from Parkinson’s disease, according to the announcement of Didion’spublisher Penguin Random House.

“Didion was one of the country’s most trenchant writers and astuteobservers. Her best-selling works of fiction, commentary, and memoir have received numerous honors and are considered modern classics,” Penguin Random House said in a statement.

As Colleen Long puts in his obituary report to the Associated Press on December 23, 2021, “Along with Tom Wolfe, Nora Ephron and Gay Talese, Didion reigned in the pantheon of ‘New Journalists’ who emerged in the 1960s and wedded literary style to nonfiction reporting. Tiny and frail even as a young woman, with large, sad eyes often hidden behind sun glasses and a soft, deliberate style of speaking, she was a novelist, playwright and essayist who once observed that ‘I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests.’ Or, as she more famously put it: ‘Writers are always selling somebody out.’

As Colleen Long puts in his obituary report to the Associated Press on December 23, 2021, “Along with Tom Wolfe, Nora Ephron and Gay Talese, Didion reigned in the pantheon of ‘New Journalists’ who emerged in the 1960s and wedded literary style to nonfiction reporting. Tiny and frail even as a young woman, with large, sad eyes often hidden behind sun glasses and a soft, deliberate style of speaking, she was a novelist, playwright and essayist who once observed that ‘I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests.’ Or, as she more famously put it: ‘Writers are always selling somebody out.’

Californian Voice

Didion was born on December 5, 1934, in Sacramento, California, U.S, and died on December 23, 2021, in New York. According to critics, it was California, her native state that provided her with richest material. British writer Martin Amis once referred to Didion as the “poet of the Great Californian Emptiness”. And the New York Times critic Michiko Kakutani wrote

“California belongs to Joan Didion”. Moreover, Al Jazeera report on her death said, “Didion was especially incisive in writing about the state. Her 1970 novel, ‘Play It as It Lays’, showed Los Angeles, through the eyes of a troubled actor, to be glamorous and vapid while the 2003 essay collection ‘Where I Was From’, was about the culture of the state, as well as herself and her family’s long history there.”

“I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means,” Didion said in a speech at her alma mater, the University of California, Berkeley, in 1975. Because of her introverted characteristic, especially towards her own soil, she stayed close to her home in California. She always wanted to secure the Californian voice, and becoming a writer with American scent.

Becoming a writer

Didion was the daughter of Eduene (nee Jerrett) and Frank Didion, a finance officer with the US army, poker player, and, after the World War II, a real estate dealer. As Veronica Horwell puts to The Guardian (on Dec. 23), “she was an army brat on her father’s stations, and her juvenile fantasies set out in that notebook were doomy – death in the desert, suicide in the surf.”

Didion was fascinated by books from an early age. She was encouraged to write by her mother, as a way of filling time - she gave her a notebook to write in her leisure time. During early period, Didion was especially impressed by the prose of Ernest Hemingway whose terse rhythms anticipated her own. She described this inspiration in her Paris Review interview:

“I probably started reading him when I was just eleven or twelve. There was just something magnetic to me in the arrangement of those sentences. Because they were so simple—or rather they appeared to be so simple, but they weren’t.”

According to the facts about her, she was both shy and ambitious, inclined to solitude, but had determined to express herself through writing and public speaking. She graduated from the University of California at Berkeley in 1956 and moved to New York for a job at Vogue after winning a writing contest sponsored by the magazine. At Vogue, she worked first as a copywriter and then as an associate editor from 1956 to 1963. It was during this period she wrote her first novel, ‘Run River’ (1963), which examines the disintegration of a California family.

Marriage

While in New York City, she met author-journalist John Gregory Dunne, whom she married and moved to Los Angeles in 1964. In 1965, they adopted their only child, Quintana Roo. They were married nearly 40 years, split their lives between Southern California and New York and managed to be leading figures in both literary circles and Hollywood. It is said that Dunne was demonstrative and garrulous while Didion came off as introverted.

Colleen Long wrote about their life as follows: “Didion prided herself on being an outsider, more comfortable with gas station attendants than with celebrities. But she and her husband, whose brother was the author-journalist Dominick Dunne, were well placed in high society. In California, they socialised with Warren Beatty and Steven Spielberg among others and a young Harrison Ford worked as a carpenter on their house.

They later lived in a spacious apartment on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, knew all the right people and had a successful side career as screenwriters, collaborating on ‘The Panic in Needle Park’ (1971), a remake of ‘A Star Is Born’ (1976) and adaptations of ‘Play It As It Lays’ (1972) and ‘True Confessions’ (1981) and Up Close and Personal (1996).”

Though their marriage was rocky at times, once, Dunne moved to Las Vegas for a while. In an essay in, ‘The White Album’, Didion wrote that they once took a vacation in Hawaii “in lieu of filing for divorce”.

Relentless critic

Didion was conservative in her early years, and even voted for Republican Barry Goldwater in 1964. During this time, she also started to contribute essays to William F. Buckley’s National Review, and began to harshly criticise some of the issues she saw. For instance, she attacked the role of religion in politics and the establishment’s “increasingly histrionic insistence” that President Clinton be removed from office for his affair with Monica Lewinsky. According to Colleen Long, “She was especially scathing about the quality of political reporting, mocking the ‘inside baseball’ journalism of presidential campaigns and dismissing Bob Woodward’s best-selling books as vapid and voyeuristic, “political pornography.”

Her essays on U.S. politics, including the Presidential election of 2000, were collected in ‘Political Fictions’ (2001).

Established writer

After 1960s, she became a critically acclaimed author and in August of 1977 she was interviewed for prestigious Paris Review literary magazine – she was two times interviewed for the magazine, both by Hilton Als.

Didion and her husband, John Gregory Dunne (who was himself the subject of a Paris Review interview in 1996), had written a number of screenplays together as said earlier.

In 1973, Didion began writing for The New York Review of Books, where she has remained a regular contributor. While continuing writing novels, she has increasingly explored different forms of nonfiction: critical essay, political reportage, and memoir. In 1979, she published her second collection of her magazine work as ‘The White Album’.

Critics’ view on Didion’s works was insightful, confessional and tinged with ennui and scepticism. The Los Angeles Times praised her as an “unparalleled stylist” with “piercing insights and exquisite command of language”. However, she was known for her lucid prose style and incisive depictions of social unrest and psychological fragmentation.

Subject area

Apart from Californian life, Didion’s subjects also include earthquakes, movie stars and Cuban exiles. But the common themes were: the need to impose order where order doesn’t exist, the gap between accepted wisdom and real life, the way people deceive themselves — and others — into believing the world can be explained in a straight, narrative line. Much of her nonfiction was collected in the 2006 book ‘We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live’, named after the opening sentence of her famous title essay from ‘The White Album’, a testament to one woman’s search for the truth behind the truth.

She once wrote: “We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.”

Didion was always a lifelong explorer. Once, she wrote about a trip to war torn El Salvador in the nonfiction ‘Salvador’, and completed another book as ‘A Book of Common Prayer’ after a disastrous trip to a film festival in Colombia in the early 1970s. ‘South and West: From a Notebook’ is her observations made while driving around the American South, which came out in 2017. The same year her nephew Griffin Dunne’s documentary ‘Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold’ was released. The New Yorker magazine called the film, which borrowed its title from another Yeats work, “an intimate, affectionate, and partial portrait”. In 2019, the Library of America began compiling her work in bound volumes.

Tragedy in life

In December, 2003, shortly before their fortieth anniversary, Didion’s husband died because of a heart attack – it occurred at their dinner table in Manhattan. In 2005, she published a memoir titled ‘The Year of Magical Thinking’ in which she recounted their marriage and mourned his loss. This became a best-seller, and won the National Book Award for nonfiction. She, then, adapted it for the stage as a monologue in 2007.

At the time of Dunne’s death, their daughter, Quintana, was at the hospital. She was suffering from pneumonia and septic shock that had put her into hospital intensive care. Didion delayed Dunne’s funeral until the daughter had recovered and coming home. But the recovery was brief and Quintana died from acute pancreatitis two months before the book’s publication. Didion and Dunne had adopted the baby on the day of her birth in 1966, and called her after a Mexican state. She became a familiar player in their pieces, often quoted, described as an insouciant user of hotel room service when accompanying her mother on book tours. Didion’s next memoir, ‘Blue Nights’ (2011) was on her grief of losing her daughter.

“Grief turns out to be a place none of us know until we reach it,” she wrote in it.

Literary oeuvre

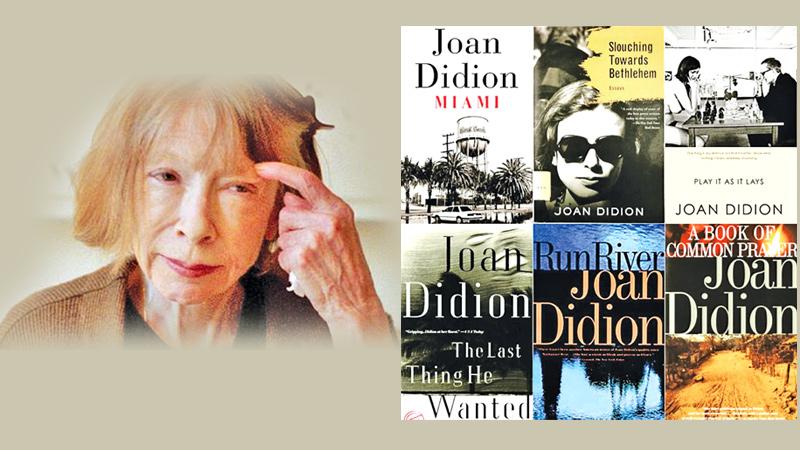

Her notable novels include: ‘A Book of Common Prayer’ (1977), ‘A Star Is Born’ (1976), ‘Democracy’ (1984), ‘Let Me Tell You What I Mean’ (2021), ‘Play It as It Lays’ (1972), ‘Run River’ (1963), ‘South and West’ (2017), ‘The Last Thing He Wanted’ (1996), ‘True Confessions’ (1981), ‘Up Close and Personal’ (1996).

Her first collection of magazine columns was published as ‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem’ (1968) and it established her reputation as an essayist and confirmed her preoccupation with the forces of disorder. In the second collection, ‘The White Album’ (1979), Didion continued her analysis of the turbulent 1960s. ‘After Henry’ (1992; also published as Sentimental Journeys) was her third collection of essays which exposed the inner decay of the establishment.

The other significant essay collections by her are comprised of ‘Salvador’ (1983), ‘Miami’ (1987), and ‘Where I Was From’ (2003).

A friend’s view

In her obituary writing, Hilton Als, a, journalist, a critic and a friend of Joan Didion, wrote to The New Yorker on December 29, 2021, as below:

“No country but America could have produced Joan Didion. And no other country would have tolerated her. Think about it. Born in 1934, and gone this month, eighty-seven years later, Didion came of age during Stalin’s reign, at a time when South Africa was instituting apartheid, when India and Pakistan were almost drowning in the aftermath of partition. Would Mao’s China have welcomed her? Or England—the country of saying the opposite of what you think so as not to cause offense? Not likely. Plus, she didn’t like England.

‘Everything that’s wrong here started there,’ she told me once, when she was thinking of cancelling a trip to London. ‘Also, so obsequious,’ she added.

‘Yes, Miss Didion. No, Miss Didion.’ Beat. ‘And they don’t mean it.’

It is appropriate to end this note with Didion’s own words about troubles in life, which were quoted by Colleen Long in his obituary writing on Didion:

“Whatever troubles we had were not derived from being writers. What was good for one was good for the other.”