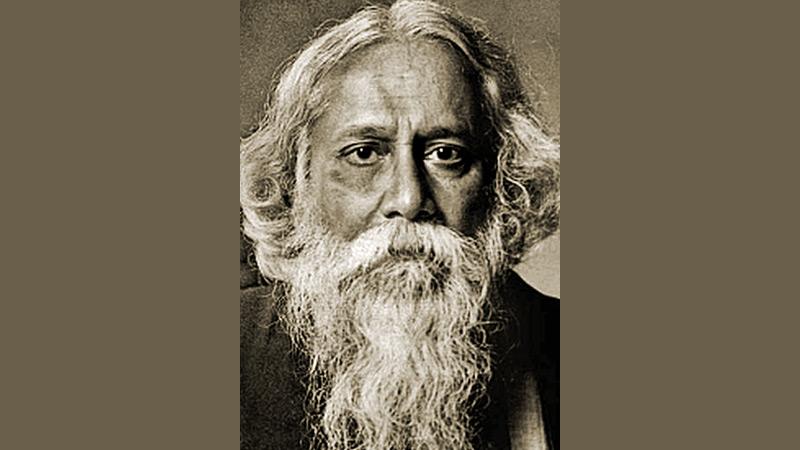

We are now experiencing a distantance education system via Zoom technology. People criticise it as a fake education, for there isn’t close relationship between children and teacher in it. But can we admire the pre-covid-19 education system in Sri Lanka? Was there a close relationship between children and teacher? Was that helpful to build a creative child with humanistic values? We can have a reasonable answer to this question if we look into the education model of Tagore. This is an ideal opportunity to go for that discussion as great thinker and poet Rabindranath Tagore’s 80th death anniversary fell on yesterday, August 7.

British education in 19th century

The greatest school for children founded by Tagore (in 1901), is Santiniketan which is an open – air school. One can call it as forest school where children learn with nature as resident students. Why was Tagore interested in such model to educate children?

The time when Tagore was born (the later part of 19th century) was not calm and serene. It was when India started to become industrialisation while an alien type British education was being established. In this backdrop it is not surprise that the school that Tagore began to attend soon became a prison. That education was manipulated by tight schedules and never was a flexible curriculum. On the other hand the education media was English.

Tagore despised this alien education media recommending it should be one’s own native language: “Learning, he said, is like eating; if the first mouthful is pleasant to the taste, the boy continues to eat with a good appetite; but if the first mouthfuls are wrapped in the indigestible cover of a foreign language, the boy’s appetite is spoiled.” (Rabindranath Tagore, Marjorie Sykes, Page 12)

His reluctance over the contemporary education also demonstrates in his short story titled ‘Once there was a king’. The protagonist in it looks forward to cut the class. Each day he prays that his tutor never come to teach him, though he never misses it. So, this is why Tagore embarked on to found an ideal school for children in Santiniketan.

Forest school

The model for the Santiniketan school for Tagore was Tapovana (hermitage) of ancient India. In this model, one would study in close proximity to nature, away from the hustle and bustle of the urban life. Secondly, he has a close relationship between Guru and the disciples – almost a family like atmosphere. Thirdly, he is in a quest to achieve higher truth – something that was hinted at in different Upanishadic texts of ancient India.

As Marjorie Sykes, a former teacher at Viswa – Bharati, describes in her book Rabindranath Tagore, Tagore wanted Santiniketan to be the first new forest school, but he didn’t want it to be just a copy of old ones. He hoped that it would have the same spirit as they did, but with a different outward form suitable to the present times.

Tagore was a poet. So, first and foremost, Santiniketan had to be a poet’s school. Once Tagore called the school itself a poem – a poem that was written on life, and not on paper: “When I brought together a few boys, one sunny day in winter, among the warm shadows of the Sal trees, strong and straight and tall, I started to write a poem ….. but not in words.” (Rabindranath Tagore, Marjorie Sykes, Pages 53)

The environment of the Santiniketan was an ideal place for a school which inspired the students. Professor Ediriweera Sarachchandra who was once a student in it, said about it as follows:

“Santiniketan in July is not Santiniketan in May. A few showers, a few cool breezes to drive away the hot air of the summer and the crescendo of the koel has made all the difference in your attitude towards life. No wonder Rabindranath wants to make all that fuss about the seasons, making songs and writing poems about every one of them.” (Through Santiniketan Eyes, Ediriweera Sarachchandra, Page 63)

Describing further life in Sanitiniketan, he says that “An ordinary day in the regular student life at Santiniketan begins at six-thirty on a summer’s days. The morning starts with upāsanā or devotions. The students all line up under the row of Sal trees, and with their palms together, repeat the Gāyatrī, the traditional invocation to the Sun. The chanting is followed by a few minutes of silence after which they all repeat the words ‘Om, sānti, Sānti’ – Peace, peace, peace.” (Page 67)

He also describes the education method at the Santiniketan as bellow:

“Most of the classes are held in the open air, under the mango groves and the Sal trees. The children carry their seats with them small square pieces of carpet which they call āsans and sit on them as they go from class to class. Under some trees there are cement seats built round in circles. It is a unique experience to round the Ashrama of a morning, watching the variety of the classes held under the groves. They range from classes in Esraj music to classes in English poetry. I can never forget hearing the little children reciting a popular English rhyme with stress on the accented syllables and an altogether Eastern intonation while the teacher kept time with his hands.

“One of the ideals of the Ashrama life and the ancient Indian ideals of education, is this close contact with nature in all the activities of the student. Rabindranath Tagore intended to apply this, as well as other ideals of Indian education, in his experiment at Santiniketan….” (Page 67)

Santiniketan is one of the very few places where education is represented in all its stages, from primary to post-graduate and research. There are many sections in the school. One is the Siksā Bhavana (primary and post-primary school). Then Pātha Bhavana (secondary school). Next the College which is affiliated to Calcutta University. Then Vidyā Bhavana (Department of Research in Indology). The extraneous departments are the Sangīta Bhavana (Music Department), the Kalā Bhavana (School of Art) and the Cheena Bhavana (Department of Sino-Indian studies).

Tagore used the word ‘home’ to describe the Santiniketan school: “a home and a temple in one place.” At another place he spoke about it as, “I prepared for them a real home-coming into this world.” In her book, Marjorie Sykes says, “Rabindranath did his best to make his school a friendly place – a place where there should be real home-like affection between the older and younger members. The teachers and the boys lived and played together like elder and younger brothers and Rabindranath played with them, and was often the liveliest of all” (Page 55)

Tagore’s thinking, on any matter, was that the best output comes from the self expression. So in the school he tried to get his students self expressed. For this he exposed students to aesthetic enjoyment as aesthetic joy refines one’s senses.

And he believed that wisdom emanates from aesthetic enjoyment, and that knowledge without the wisdom has no value. Therefore, Santiniketan education invariably included the aesthetic education. Supriyo Tagore, Principle of Pātha – Bhavana (Secondary School) in Santiniketan describes about it like this:

“Along with the usual academic subjects of a school, children were exposed to music and dance, various crafts and play-acting in the school. They played games in the afternoon. Tagore thought that man is born in the world with only one advice from God – that is ‘Express yourself’ Therefore, children of the ‘Poet’s school’ were allowed to express themselves through tune and rhyme, lines and colour and through dance and acting. (India Perspectives, Special Issue for Tagore’s 150th death anniversary)

As stated earlier Tagore relied on free education with nature. He pointed out a three-fold relationship between student and environment. One was Karma or action. It means if one trains in various physical activities, he can develop his physical work. Second was Jnana or knowledge which means one should gather knowledge about his environment - with that knowledge, he can learn the natural rules and correlations of nature, and then be aware of unity in the world diversity.

Third was Prema or love. That binds an individual to nature and to the world of man. Through love an individual losses his identity and becomes one with the world which is why Tagore removed the religion, caste, nationality and all of divisions in society from his education system - he did not believe in trying to teach religion to children by set lessons in school.

“True religion, he said, is not to know any set of historical facts, but to feel the reality of God. Children will learn of God naturally if they live with people who love and worship Him, and with the beautiful things which God, the ‘World-Poet’, pours into His world,” said Marjorie Sykes.”

The finer things in life can never be taught in a class. Children imbibe them from the environment or from the personalities around them. So Tagore believed that it was essential to create a proper environment in school to bring out the dormant qualities in a child.

The poet felt that a person was not fit to be a teacher if the child in his mind was not alive still. So they had to share their experiences with children. And he thought one should always be aware of his audience too if he is going to cater them. Therefore, he allowed his students to visit the villagers’ houses nearby, because they had to be aware of the problems of them. Any education distant from the ordinary people’s affairs was meaningless to him.

Inspiration from religions

Udaya Narayana Singh, an eminent poet, playwright and former Director of Rabindra Bhavana at Visva – Bharati, reveals another aspect of Tagore’s thinking. Recounting to India Perspectives, Special Issue, he spoke about the building up a proper value system inspiring from world religions:

Tagore said “we need to develop a system that draws from civilisational histories of ‘Vaidika’ (Vedic), ‘Pauranika’, ‘Bauddha’ (Buddhist), ‘Jaina’, ‘Muslim’ (Islamic) traditions of education and discover our own pathways to prepare the new generations and help emerge men and women with appropriate leadership qualities.

He says – if you do not know yourself in detail and in an involved manner, you cannot build an ‘India’ by aping and copying others. You can do so only by learning to converge various traditions, or else – we could at best build a second rate system that depends on ‘transfer’ of knowledge and technology.”

In this way, we can see how Tagore’s method of education is formed and how to develop our education system. When the time passes, we tend to forget the past. But some events in the past we cannot ignore, because they are not stale, they are still with us. The great poet Tagore’s views are like that. We can inspire from them not just to build up a proper education system, but also to answer the current socio-political issues we are burdened with.

A quote from Marjorie Sykes’ observation on Tagore’s religious practices at Santiniketan:

“Rabindranath taught the children to sit in silence for a quarter an hour, at sunrise and sunset every day. He did not tell them what they should think about in the silence, or ask them afterwards how they had spent their time. He believed that the time of quiet was in itself good for body, mind and spirit and that the beauty of their surroundings would of itself, and without any effort, help their minds to grow.

After the silence the whole school gathered together and chanted a prayer. The words were chosen by Rabindranath; they are in Sanskrit, but he took care that all his boys should understand their meaning. Here is a translation of part of the prayer:

‘Thou art our Father; help us to know that Thou art our Father….

‘O God our Father, remove from us the world of sin and give us what is good.

‘From Thee come the enjoyments of life, from Thee comes the welfare of man.

‘I bow to Thee. Thou art the Good, the highest Good.’”