Sunil Sarath Perera is a veteran Sinhala lyricist, poet and writer. He has created many famous Sinhala songs sung by Maestro W.D. Amaradeva, Prof. Sanath Nandasiri and Somathilake Jayamaha. He has written several poetry books, including recently published Mal Mada Bisav and two memoirs: Maya Mawatha (Maya Avenue), Hudakala Mathakaya (Lonely Memory) and a few classical books on Sinhala songs and poetry. The Sunday Observer spoke to him to discuss Sinhala sons and its lyrics.

Excerpts

Q: You are a lyricist. How do you de fine lyric?

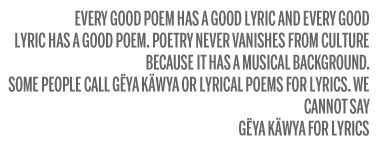

A: Every good poem has a good lyric and every good lyric has a good poem. Poetry never vanishes from culture because it has a musical background. Some people call Gëya Käwya (ගේය කාව්ය) or lyrical poems for lyrics. We cannot say Gëya Käwya for lyrics. I suppose Artha Käwya (අර්ථ කාව්ය) or meaning centred poems for lyrics. A lyric has not only a meaning, but also a lyrical language and an emotional quality (භාවිකාර්ථ). However, there is no lyric without meaning.

Q: Why can’t we call Artha Käwya for poetry?

A: Yes, we can call Artha Käwya for poetry too, because poetry has a lyrical quality that comes from the language.

Q: How about Sïgiri Gee or Sïgiri Graffiti (සීගිරි කුරුටු ගී)? Are they lyrical poems or meaning centred poems?

A: We can identify prose, poems, lyrical poems and meaning centred poems in Sïgiri Graffiti. Sïgiriya altogether is a poem. Its Lions’ den or Sïnharüpa, its landscape, its graffiti and frescos altogether is a poem. Sïgiriya has a rich architectural heritage. It has poetic characteristics. Every good architectural element has a poetic characteristic.

Q: If we say Artha Käwya for lyrics, isn’t there a philosophical meaning in it?

A: Yes, there may have a philosophical meaning, but a lyric has to have an emotional quality and poetic language. There are all these characteristics in Guttila Kawya (ගුත්තිල කාව්ය). There is no poem or song without a meaning.

A: Yes, there may have a philosophical meaning, but a lyric has to have an emotional quality and poetic language. There are all these characteristics in Guttila Kawya (ගුත්තිල කාව්ය). There is no poem or song without a meaning.

Q: You brought an idea of philosophical poeticism or Därshanika Kavitäva (දාර්ශනික කවිතාව). Is there any connection between this and meaning centred poetry?

A: Yes. In Därshanika Kavitäva, I mentioned the significance of meaning in poetry. There is a connection between the two matters. We can identify this philosophical poetry in Madawala S. Rathnayake’s and Manawasinghe’s lyrics.

Q: What is your view on Sinhala poetry?

A: A poem should have a meter or Viritha (විරිත). We can identify a rhythm with that meter or Viritha. For instance, There is a meter and a rhythm in Gunadasa Amarasekara’s poetry. There is also a meter or Viritha or Chandasa (චන්දස) in Wimal Dissanayake’s poetry. There is a rhythm in it. But in Siri Gunasinghe’s poetry, we don’t see a meter, but there is a rhythm in it. He isolates words to get a Dhwani (ධ්වනියක්). However, we don’t see meter poetry or Virith Käwya after these poets. Instead, we can identify philosophical poetry and short poetry or so called Haiku Poetry which I mean fake poetry among them. I call this poetry as Atasekili poetry (ඇටසැකිලි කවි) or skeletal poetry. I don’t see any real poetry today.

Q: What are the suggestions to improve Sinhala poetry?

A: We can make use of Sinhala classical poetry and world literature to develop Sinhala poetry. For instance, there is solitary poetry called Mukthaka (මුක්තක) in classical Sinhala poetry, especially in Sïgiri Graffiti. We can make use of it, because poetry is a concise medium. We can have inspiration from world literature. We can benefit from Haiku poetry (අයිකු කවි). Some people think that Haiku is a short poetry, but it is incorrect. Haiku has three characteristics. First, it should have three lines in which first line has five Mathras (මාත්රා) while the second line has seven Mathras and the third line has five Mathras making 17 Mathras altogether in a Haiku poem. Second, it should have a seasonal affair (සෘතු සම්බන්ධයක්). Third, there should have a certain image in a Haiku. We can feed Sinhala poetry and Sinhala lyrics from these literary qualities.

Q: How do you see the criticism of Sinhala poetry?

A: We don’t see any classical foundation in criticism. Gunadasa Amarasekara and Wimal Dissanayake are the only critics in Sri Lanka.

The Gëya Käwya idea is the classic example which shows our downfall of poetry criticism. Gunadasa Amarasekara once called these words Gäya Pada (ගාය පද). The Gëya Käwya idea was first introduced by Prof Sunil Ariyarathne who thought Gëya Käwya is depicting the singing quality of lyrics (ගායනාකල හැකි බව). If we say Gëya Pada for those singing words, we have to use it for the words of a Sinhala song, Prutugeesi karaya ratawal allanna suraya (‘පෘතුගී්රසි කාරයා - රටවල් අල්ලන්න සූරයා’) by Arisen Ahubudu. Can we say Gëya Pada for words, such as Gahanna wenawa Wedunoth Loketamukku (‘ගහන්න වෙනවා වැදුනොත් ලෝකෙට මුක්කුු’)?

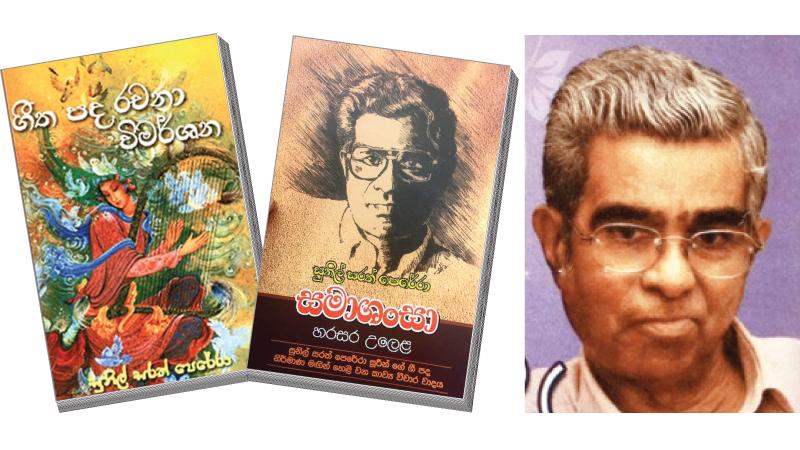

Even Prof. Sarachchandra did not use these words for songs, instead he introduced his operatic drama, Lömahansa as Geetänga Nätakaya. MahagamaSekara called Geethapadarachanaya (‘ගීත පද රචනය’) and Manawasinghe called Geetha Prabandha(‘ගීත ප්රබන්ධ’) for lyrics. Arisen Ahubudu said it Gee Pabanda (‘ගී පබඳ’), Tagore also introduced his lyrical poetry book as Geethänjali, not as Gëyaanjali.

Q: What is the source of Gëya Käwya?

A: There is a word, Wäggëyakäraya (වාග්ග්යකාරයා) used in teaching the Hindustani music. It is called for a person who does three tasks in music: writing lyrics, producing music and singing songs.

Q: You consider Cumarathunga Munidasa as a significant poet in Sinhala. What is his influence on Sinhala lyrics?

A: Mahagamasekara, a major Sinhala lyricist and poet stated in his collected volume of Sinhala lyrics that he had started to write lyrics by reading Cumarathunga’s Hela Meeyesiya. There are many lyrical forms and nationalistic lyrics (ජාත්යානුරාගී ගී) in the book. He wrote many beautiful poems which became famous songs, such as Sanda Paane Weli Thala (‘සඳපානේ වැලිතලා....’). His influence is immense.

Q: We see wrong names for lyricists of some of the famous songs broadcast by some electronic media?

A: It is a mistake we experience in electronic media. The song Chando Ma bilinde nubanaadan (‘චන්දෝමා බිළිදේ නුඹ නාඬන්....’) sung by Amaradewa and his daughter has been written not by Rathnasri Wijesinghe, but by Ambanwala Räla or Ambanwela Nilame who lived in the Mahanuwara era. Ambanwela Nilame was a poet in poetic court (කවිකාර මඩුව) of Räjasinghe 11. The king had a Vedi wife from Mahiyanganaya where the King’s palace was, and Ambanwela Nilame wrote it through his experiences. However, in Youtube, it is mentioned as a song of Rathnasri Wijesinghe. This song was first sung by Dewär Süriyasena and Suchithra Mithra, a singer from Wanga Deshaya. Some critics say it is a Vedi song, but it is not. It has characteristics of Prashasthi Käwya or praising poetry.

There are other problems in misusing these real names. One such problem is about paying royalties for songs.

Q: Do you receive royalties?

A: I didn’t receive royalties until recently. It started because of the foundation of Jayantha Darmadasa’a Geetha Nibandakayange Sansadaya (Sinhala Lyricists’ Association), but after the Corona pandemic, it has stopped.

Q: Don’t you receive royalties from electronic channels?

A: It is a fraud. They pretend to pay, but it is not a constant process. When I was the chairman of the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation, I opposed to pay royalties for artistes.