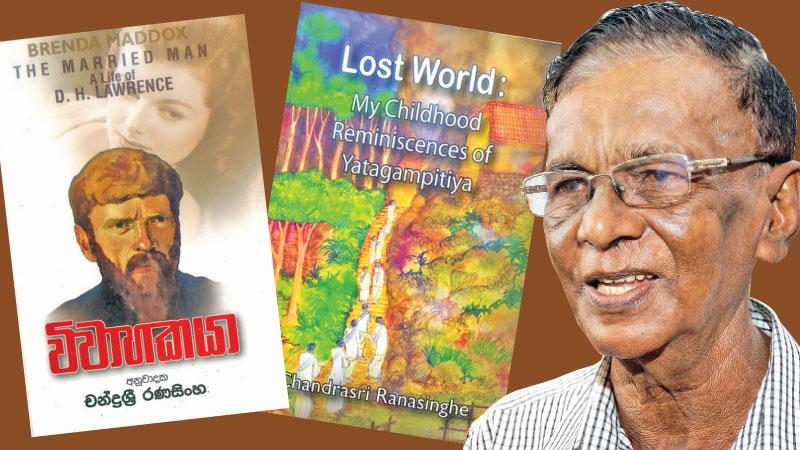

Chandrasri Ranasinghe is an award winning Sinhala writer with a focus on folklore. His Sinhala translations of Seligmann’s The Veddas which has 660 pages, and Henry Parker’s Village Folk Tales of Ceylon (third volume) which has 512 pages, won the state literary awards for the best classical translation in 2010 and 2013. His book, Ahiguntika Janakatha (Folk Tales of Gypsies) won the state literary award for the best classical translation in 1973. His new Sinhala translation was launched recently as Viwahakaya (‘The Married Man: A Life of D. H. Lawrence’ by Brenda Maddox), published by Fast Publishing. The Sunday Observer met Chandrasri Ranasinghe to discuss his book and the literary life of world renowned writer D.H. Lawrence.

Excerpts:

Q: How do you introduce this book, Viwahakaya?

A: This is a comprehensive biography on David Herbert Lawrence or D.H. Lawrence. Lawrence, the British writer is the most controversial novelist of his time, mainly because of his novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928) and later its trial. He was born on September 11, 1885 and died on March 2, 1930. The book covers all the major and minor incidents in his life from the beginning to the end.

Q: Lawrence comes from a poor family. His father was a coal miner?

A: Yes. He is the fourth child of Arthur John Lawrence, a barely literate miner, and Lydia Beardsall, a former pupil teacher who had been forced to perform manual work in a lace factory due to her family’s financial difficulties. Lawrence spent his formative years in the coal mining town of Eastwood, Nottinghamshire. His working-class background, the tensions between his parents and troublesome life provided the raw material for his early works. Lawrence roamed out from an early age in the open, hilly country and remaining fragments of Sherwood Forest in Felley woods to the north of Eastwood, beginning a lifelong appreciation of the natural world, and he often wrote about ‘the country of my heart’ as a setting for much of his fiction.

Q: Though Lawrence wrote major novels, such as Sons and Lovers, The Rainbow, Women in Love, his name took the world attention after his controversial novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1928?

A: Yes. At first, Lady Chatterley’s Lover was not published in England or America, but in Italy and France as private editions. A heavily censored abridgement of the book was published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf in 1928. When the unexpurgated edition of it was published by Penguin Books in Britain in 1960, the trial of the book under the Obscene Publications Act of 1959 became a major public event and a test of the new obscenity law. However, after the court decided the book was not an obscene novel, there emerged a huge public reaction and the 1959 Act had made it possible for publishers to escape conviction if they could show that a work was of literary merit. Nevertheless, Lady Chatterley’s Lover became a pathfinder in that respect.

Q: How about your evaluation of the book?

A: Lady Chatterley’s Lover is not just a trash, because there is an aesthetic value in the novel. I believe it’s a literary novel. However, at the time of his death, his public reputation was that of a pornographer who had wasted his talents. E. M. Forster, in his obituary notice, challenged this widely held view, describing him as “the greatest imaginative novelist of our generation.” Later, the literary critic F. R. Leavis championed both his artistic integrity and his moral seriousness.

Q: Lawrence’s themes are also dealing with serious issues?

A: Lawrence started as a poet and switched into the fiction. His collected works represent, among other things, an extended reflection upon the dehumanising effects of modernity and industrialisation. Some of the issues Lawrence explores are sexuality, emotional health, vitality, spontaneity and instinct. Nevertheless, his opinions earned him many enemies, and he endured official persecution, censorship, and misrepresentation of his creative work throughout the second half of his life, much of which he spent in a voluntary exile he called his “savage pilgrimage”. According to the author of ‘The Married Man: A Life of D. H. Lawrence’, Brenda Maddox, he gives to the sexual act a weight it will not bear.

Q: Does the writer have any personal experience behind the Lady Chatterley’s Lover?

A: Lawrence had several love affairs and finally married Frieda von Richthofen Weekley, a wife of his former modern languages professor at University College, Nottingham in 1912. She was a translator, mother of three children and six years older than him. She was a German noble lady, but dominating one. Critics say that the obscenity in his novels comes from her influence on him. They both were unfaithful to each other in their fashion but the bond lasted until the end of his life.

He once told Frieda that, “Nothing has mattered but you”. Hence, critics say that the things behind Lady Chatterley’s Lover might come from Frieda’s dominating role on him. Her influence on his work can scarcely be exaggerated. To an acquaintance asking what his message was, Lawrence wrote, “You shall love your wife completely and implicitly and in entire nakedness of body and spirit, this that I tell you is my message as far as I’ve got any.” However, according to Brenda Maddox, Lawrence’s sexuality remains ambiguous; he was accused of being both a repressed homosexual and a heterosexual sodomist.

Q: This book, Viwahakaya describes Lawrence character as well?

A: Brenda writes in his introduction to the book, “He is both sympathetic and offensively hostile to the woman. The cannon of his utterance can be mined to yield opinions for and against almost any subject close to his heart: mothers, the working class, education, England and English, the United States and Americans, Jews, Italians, Indians, war, sunshine and his pets. He was an infuriating friend: one minute, full of understanding, amusing and generous, and the next, angry, preachy, disloyal and ungrateful.”

Q: Lawrence once visited Sri Lanka?

A: He visited Sri Lanka, then Ceylon on March 13, 1922. His wife Frieda also came with him. On January 27, 1922, Frieda wrote a letter to her friend mentioning this visit:

“We were coming straight to you at Taos but now we are not. L says he can’t face America yet. He doesn’t feel strong enough! So we are first going to the East to Ceylon. We have got friends there, two Americans, ‘Mayflowerers’, and Buddhists. Strengthened with Buddha, noisy, rampageous America might be easier to tackle.”

On March 13, 1922, the Osterley, the ship Lawrences embarked on, docked at Colombo. After disembarking, Lawrence had looked around and told Mrs. Brewer, one companion of their voyage, “I shall never leave it.” Brenda Maddox describes the visit:

“Six weeks later he left. He had had enough ‐of the heat, the heavy, sweet smell of fruit, coconut and coconut oil. He never felt so sick in his life. He found the little temples vulgar, the faces of the yellow ‐ robed, shaven ‐headed monks nasty. As for the birds and beasts of which he was usually so fond, they ‘hammer and clang and rattle and cackle and explode all the livelong day, and run little machines all the livelong night.’ In sum, the East was ‘too boneless and negative…. I don’t like it one bit.’

“A racial theory followed: the East was no environment for the white man, but rather for the dark ‐skinned, whose blood ‐consciousness was turned to the sun and the heat. Lawrence did not like the races to mix.”

However, Lawrence’s visit coincided with the Prince of Wales’ visiting to Ceylon. So he had a rare chance to see an elephant procession organised to accept the Prince. He wrote a poem, called ‘Elephant’, on the incident. Brenda writes, the poem “captures the absurdity of the spectacular elephant procession put on for the ‘pale little wisp of a Prince of Wales, diffident, up in a small pagoda’ while the ‘mountainous vast ‐blooded beasts’ bow down to him. Following is two lines of the poem:

“Serve me, I am meant to be served.

Being royal to the gods.”

Q: Lawrence died of tuberculosis at 44?

A: Yes. It is so unfortunate to lose such a great writer at 44. But why did Frieda, his wife not force him to seek treatment for his illness? Why did she remain with him to the end? Brenda writes, “He was probably the least skilled of her lovers; he told her she was a fool, when she was not; he hit her and swore at her….”

Q: There is some resemblance between Lawrence and Joyce when we read their literature?

A: Yes, Brenda compares those writers closely. She said,”Lawrence and Joyce are the English and Irish sides of the same coin: twentieth century exiles who, from within the safety of marriages to strong woman, liberated the English printed word and who acquired unjustified reputations as pornographers and libertines. Both writers utterly rejected the First World War, turning their backs on it to write their masterpieces about the wider war, between men and women. Ghostly mothers haunt their works. So do anal preoccupations, which their followers were very slow to recognize.”

Q: According to some critics, Lawrence’s explicit portrayal of sexual scenes in his novels, has some philosophy?

A: Lawrence was a philosopher himself. He thought one should not suppress his feelings, but let feelings go freely. And as he was an emotional character too, he thought we should not obstruct our life. However, he didn’t publish Lady Chatterley’s Lover in England, because England had a very conservative background at that time.

Q: Viwahakaya has 639 pages. How long have you been translating this book?

•A: About eight months. The bigger book is the original book, ‘The Married Man: A Life of D. H. Lawrence’. I did some sort of adaptation from the original one. If I translated the whole book, it would have been exceeded 100 pages and boring to the reader. I selected the important and interesting points of his life, and translated, but I was faithful to the original book too. I tried to make the translation more readable.

Pix by Nishanka de Silva