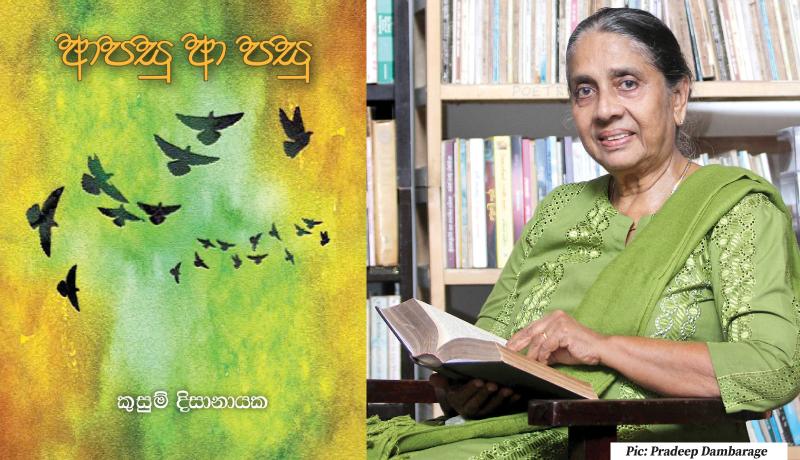

Veteran writer Kusum Disanayaka recently launched her second poetry book: ‘ආපසු ආ පසු’ (After the Return), published by Sumitha Publishers and distributed by Sarasavi Publishers. Kusum is a writer in various genres of literature, including novel, short story, poetry and translation. Wife of Prof. J.B. Disanayaka, Kusum, is a former Sinhala teacher at Visakha Vidyalaya and Thurston Vidyalaya, Colombo, and has written over 100 books. The Sunday Observer met her to seek her views on her work.

Excerpts:

Q: How did this book come about?

A: For me, poetry is not what I write, but what gets written. This book, Apasu Apasu (‘ආපසු ආ පසු’) consists of poems written at various times. Most poems are personal ones and some were written for certain publications. When there were a sufficient number of poems for a book, I publish them.

Q: Generally, you write in prose, though this is a poetry book?

A: I like poetry very much. The poet in me was inspired by the poetry that Iread in my childhood days. We heard many beautiful poems in our early days, but we cannot hear such poems now. Poetry is a part of human kind. It is a meeting with nature. When we were small, we used to look at the night sky, the sky full of stars. Today, how many of us can see the night sky full of stars? It is not a surprise that we are breaking away from poetry now.

Q: You were always interested in Sinhala classical poetry?

A: Yes, very much. Kaw Silumina is my best Sinhala poetry book followed by Gutthilaya, Selalihini Sandeshaya and Mayura Sandeshaya. When we read the woman dancers' act in Gutthilaya and Mayura Sandeshaya, we can see that the sound and meaning are merged. Poetry is produced by the combination of meaning and sound. With the association of this type of classical poetry, our creativity in poetry was naturally developed.

Q: What is poetry?

A: A poem should speak to one's heart as well as one's brain. According to ancient Sanskrit criticism, art should begin with delight and end with wisdom. Similarly, poetry also begins with delight and ends with wisdom.

Anyone who is in the company of poetry cannot reject this idea. If a poem exclusively speaks to one's heart, there is no value of it. It should influence us to think about things too.

Q: Do you accept the concept of HadaBasa by Gunadasa Amarasekara?

A: Yes, absolutely. Poetry touches our heart and thereafter, we tend to think about it. Gunadasa Amarasekara says there should be a poetic language in a poem. That is correct. We love to read Sinhala classical poetry because of its beautiful language. And I think a poem should have a rhythm. Without a rhythm, there is no poetry.

Q: How about the meter or විරිත?

A: I don't believe in the meter of Samudra Ghosha, or the meter of Gee. I believe in a rhythm that comes out from the experience of poetry. Look at those poets such as Mahagama Sekara, Chandrarathne Manawasinghe and Monika Ruwanpathirane. None of them lack rhythm in their poems. Their poetry still delights us because of that. Mahagama Sekara wrote a book on rhythm, which is his Ph.D. thesis. When we read Gunadasa Amarasekara's poems in Bhawa Geetha, his first poetry book, we can understand how much he gained from rhythm:

චිරි චිරි ිචිර ිචිරිඋදේද සිටඇදහැලෙන

පොදනොකැඩිතෙතබරිව හිරිකිතෙන් කිලිපොළන

පාරතොට, ගහකොළද වසා ගෙන හැමඅතින

වහින වැහිව හිනවැහිනොපායන මුළුදවස

(‘වැස්ස’ - Rain)

යමන්කළුවෙගෙදරයන්න, කන්දඋඩින්අඳුරඑනව

උඹටවගේමගෙඇඟටත්හරිමවිඩාවක්දැනෙනව

අඳුරතමයිඅපෙඇඟපත, නිවන්නදෙවියන්එව්වේ

හණිකයමන්ගාල්වෙන්න, පිදුරුගොඩේගෙයිමුල්ලේ

(‘අඳුරඅපේදුකනිවාවි’ – Darkness will kill our suffering)

There are rhythms in these poems, but they don’t come from outside, but from the experience of poetry itself. When we read Geethanjali by Tagore, its rhythm comes from poetry itself.

Q: How do you think about the younger generation?

A: The youth more or less speak to the brain of the reader; they do not care about poetic language or its appeal to the heart of the reader. Without aesthetic values, especially, Chamathkara Rasa, there is no poetry. Understanding is necessary, but understanding should come from delight. Poetry takes us from delight to wisdom. The younger generation must be aware of this fact.

Q: Do you follow other poets?

A: I am not writing poetry, poetry writes itself for me. So, there isn’t anyone for me to follow. But if I read others’ poetry, I am automatically building up my own poetry.

Q: You translated Tagore’s Githanjali into Sinhala?

A:Yes. I should say that poetry translation is also, in a way, a creative process. When I translated Githanjali into Sinhala, I didn’t translate it from beginning to end. My mood in the circumstances selected the poems that I translated each time. The whole book was finished by the gradual translation of various poems in various places.

The original Githanjali in the Bengali language is in fact written in verse, but when it was translated into English, Tagore wrote it in prose. He wanted the English people to understand it. Though I read the English translation of Githanjali, I translated it into Sinhala in verse.

Q: You write poems as well as short stories. How do you distinguish between material for a poem and material for a short story?

A: Short story is also in a way a poem. But for me, a poem is more sophisticated and sharp in feelings than a short story. Also, a poem is about just one thing and short story can go further. There is no division in selecting material for a work. Actually, the material or experience selects the work to be a poem or a short story.