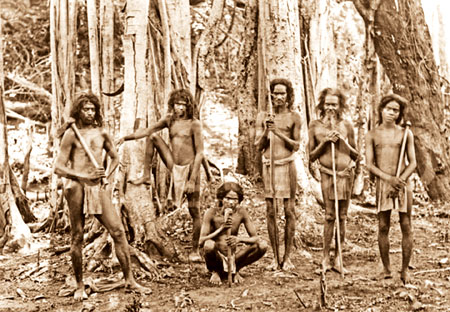

The dense forest is a wild sanctuary. Within this natural realm tribes of people have lived for centuries, from the native Indian tribes of the Cherokee in the US, the Aborigines of Australia to the Masai Mara in Tanzania. Centuries ago, there lived a clan of people in the jungles of Sri Lanka. The chroniclers of the Mahavamsa had reason to believe that these primitive citizens were members of the Yakka tribe. When the banished Indian prince Vijaya landed on our shores, it is believed that he acquainted Kuveni, the defiant leader of her clan. Some opine that their offspring grew in number. Subsequently, these wild children wandered into the hills of Samanalakanda (Adam’s Peak). The Sabaragamuwa Province is said to have been an abode of the Veddahs as the word Sabara-gamuwa denotes, village of the sabara (forest dweller). Today, this region is popular for its expensive gems. What remains of these original tribes to a certain extent are found today in the North Central and Eastern Provinces. The four main clans are Uruwarige, Thalawarige, Moranawarige and unapanawarige.Today, I wonder if there is a Veddah of ‘pure blood line’ as they have integrated into village communities. In 1953, the census showed 803 Veddah and in 1963 the number yielded only 400.

White Blood Brother

When we talk of Veddah there is one name that springs to mind, the late Dr. Richard Lionel Spittel or R.L.Spittel as he was known. During his time he was a gifted surgeon. He enjoyed hunting. One day, he had an encounter in the wilds that changed his focus. After shooting a deer, he found the innocent fawn nearby. He was upset and wrote a poem titled, ‘The wounded doe’. Since that day he stopped hunting. He took an interest in finding the elusive Veddah. Thus, he ventured by canoe along the Mahaweli Ganga towards Dimbulagala, to the rock known as Gunners Quoin. When he met the Veddah they gradually built a bond. Dr. Spittel earned the clan’s trust and became their “hudu hura”- white blood brother. He found that the tribe was affected by malaria and malnutrition. He spent much time in the forest and became a crusader for the Veddah and wrote many books. Another author, Leonard Woolf also wrote a book titled, Village in the Jungle (1913) where the main character is Silindu a Veddah.

Patient predators

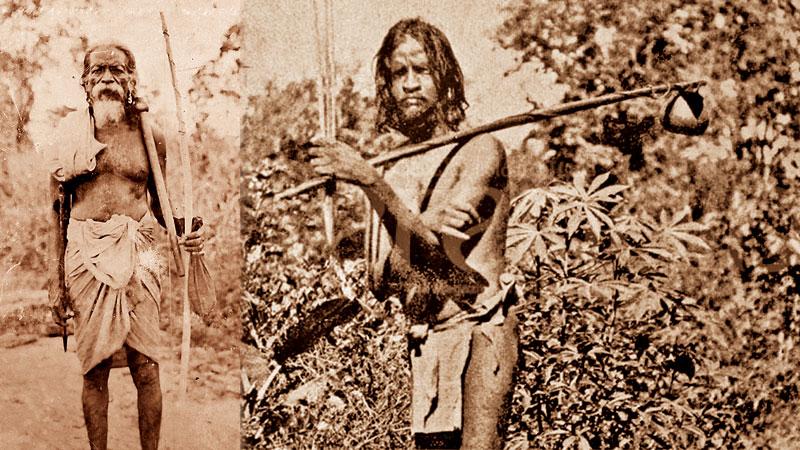

The agile Veddah showed their prowess as stealthy hunters. They followed their prey, hunting only for food. Unlike other tribes across the world they did not store their meats, maybe this is because there was an abundance of game and they didn’t encounter a winter. Their weapons of choice were the bow and arrow, hand axe and spear. They tracked down deer, monkeys, wild boar, tortoise, monitor lizards, turtles and rabbits. The flesh of the brown monkey, shared around a fire remains a tasty treat. Living in the dense forests requires energy. The Veddah men experimented with the art of stunning fish with poison taken from the cactus plants, with tiny amounts mixed into the lake. At times, the women ventured with the men to gather fruits, nuts and yams. The most desired find was a honey comb. The bold Veddah would release smoke and gently scatter the bees (this same practice is used in Brazil and Africa). They pioneered the science of food preservation, soaking venison in honey. I was bestowed this delicacy three decades ago via a friend. After adapting to rudimentary forms of cultivation, kurrakkan is also part of their diet. I have heard that the signature dishes of the original tribes are gona perume (a meat dish layered with fat) and goya thel perume (the tail of the thala goya roasted on slow burning embers). To the Veddah clansmen, hunting is a time-honoured ritual, where they dance and make incantations under moonlit skies to seek the blessings of dead ancestors. The highly superstitious community venerated the spirits Kande yakka, Bilinda and Nae Yakka.

Their minds were focused on pleasing their ancestors who they believed would guide them towards the prey. The hunting party, often weary from trekking shared their kill. Hunters often got cuts and bruises, and the Veddah used herbs and roots in the forest as simple, yet, effective remedies.

Their minds were focused on pleasing their ancestors who they believed would guide them towards the prey. The hunting party, often weary from trekking shared their kill. Hunters often got cuts and bruises, and the Veddah used herbs and roots in the forest as simple, yet, effective remedies.

Oil from the python (pimburu thel) was used to restore fractures. The communication pattern of the tribe is not fully understood. There is debate if the Veddah dialect derived from some Indian dialect or if it is loosely based on an ancient form of Sinhalese. Over the years, the hunters in the Eastern Province have incorporated words from Tamil into their dialect. Apart from language, the Veddah use a series of bird calls and hooting as signals. To date, there is no trace of the Veddah having written anything, though some cave drawings have been discovered.

Wild weddings

The folks of Mahiyangana, Bintenne and Dambana sustained their clan, often intermarrying. The Veddah wedding ceremony is very basic. The prospective groom returns from a hunt, bringing a rabbit or a monitor lizard, along with that of a honeycomb. He waits expectantly outside the hut of his young bride. The girl’s father leads her outside and places her hand in the hand of the hunter. She ties a cord (diya lanuwa) around his waist, a primitive vow of endearing love. The bride’s father then presents a bow and an arrow to the man. The couple leaves. Today, the remaining Veddah have abandoned their loin cloth for a short sarong, and the once bare-breasted women wear a blouse that really has no design. Those who moved to rural villages have adapted to a better lifestyle and engage in putting on frenzied displays for visiting tourists.

Robert Knox wrote about the Veddah as a tribe of ‘wild men’, when he was imprisoned in Kandy. The Veddah were deployed as military scouts during the reign of King Parakramabahu, Dutugemunu, Rajasinghe II and the revolutionary Keppetipola Dissawe.

When a death occurred in the clan, the body was left behind in a cave and covered with leaves. Some had a habit of sprinkling the corpse with lime juice and keeping three open coconuts. The dead hunter’s bow and arrow was kept by his side. The Waniyela Aetto venerates the sun (Maha Suriyo Deviyo). They undertake a long journey on foot to the temple of Kataragama.

In a lifestyle empowered with digital influence and cultural assimilation, Sri Lanka’s indigenous clan may soon be a memory of the past, and reduced to some photos in a travel website.