A world apart from the buzzing city of Colombo, we pass thick forest, shrub jungle, irrigation tanks, paddy fields and small hut-like houses. We are on our way to meet Velayudan, whom we were told, lives in Kunjankulam, in Madurankulam, Vakarai. As we trek the path, I’m reminded of the renowned British doctor, Charles Gabriel Seligman and his wife Brenda Seligman the first to trek these trails in search of Velayudan’s ancestors in the beginning of the 20th Century. A century had passed. Chances are, change would have had its way with these communities.

The Seligmans were famed throughout the world for their arduous field research of the indigenous people of Sri Lanka, the Veddas. Their joint publication ‘The Veddas’ was recommended as a textbook of anthropology in many Universities. The Seligmans spent long years researching the Vedda ancestry. They were the first to reveal that the Veddas live in the coastal areas. Though much was known about the community of indigenous descent living in the dry zone forests in the central plains, the Coastal Veddas had no such recognition, except a fading trail left in folk lore of yore. Thanks to the Seligmans’ in depth research, much about coastal veddas is known to us today. This is 2018, a century after the Seligmans visit and anticipation could make you faint.

The Seligmans were famed throughout the world for their arduous field research of the indigenous people of Sri Lanka, the Veddas. Their joint publication ‘The Veddas’ was recommended as a textbook of anthropology in many Universities. The Seligmans spent long years researching the Vedda ancestry. They were the first to reveal that the Veddas live in the coastal areas. Though much was known about the community of indigenous descent living in the dry zone forests in the central plains, the Coastal Veddas had no such recognition, except a fading trail left in folk lore of yore. Thanks to the Seligmans’ in depth research, much about coastal veddas is known to us today. This is 2018, a century after the Seligmans visit and anticipation could make you faint.

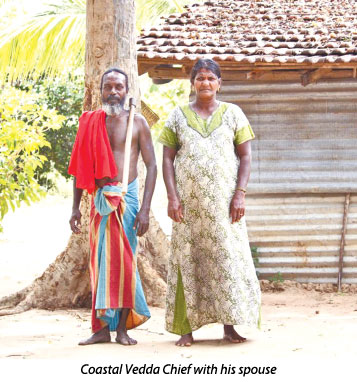

We reach Velayudan’s village. An old woman squats in front of a house deeply focused on de-husking a few betal nuts. Two toddlers play catch, running around her. Perhaps they are her grandchildren. This is the house of Velayudan. But, he was not home. He is out visiting a neigbour. The woman sends for him. Soon, we see a man on a push bicycle, an axe resting on one shoulder and a rusty piece of cloth hung on the other, his long hair tied in a knot. His physique and features bear a strong resemblance to the indigenous community of Veddas pictured by Seligman, more than those of the inland community who pretend to take their ‘look’ by the way they dress. This is Nallthambi Velayudan, the leader of the Coastal Veddhas.

“We belong to the Coastal Vedda tribe. We also have a few clans. I am of the Ambala clan. I was born in Mankerny, when our ancestors were living in the forest the British authorities had settled them in Mankerny. However, they had gone back to their homelands in the forest as they were not used to living outside in the villages. Those days our people cultivated maize and finger millet in the chenas. They used to hunt and fish. Later when the governments prohibited the clearing of forests for chena cultivation, they gave us this village as a settlement. That had been in 1966. We have been living here since. We used to erect our huts using iluk (sword grass). During the years of war, we had to leave the village from time to time. When we came back there was nothing left of the village. The elephants had run amok and had destroyed all the houses. After the war, the government built us permanent houses,” says the leader of the Coastal Veddas. There are about 22 villages in the Batticaloa district with coastal Vedda settlements. In Kirimichchai, a nearby village, there are 95 coastal Vedda families, he informs us.

The Seligmans’ had noted that the Coastal Veddah population is higher than that of the inland – (Gam Vedda and Gal Vedda) populations. Seligman reasons that the higher numbers could be due to the Coastal Vedda population being mixed with the Tamils in the area. However, Velayudan is of a different opinion. Intermarriage of the present generation is a problem that the indigenous people face, says Velayudan. “Mixed marriages happen in the new generation. Mostly those who marry outside the tribe settle away from the villages. Only a few live among the clan, within our villages,” say Velayudan. At present in his village, Kunjankulam, there are 64 families who have not intermarried with other communities

However, etched deeply and entwined with the Coastal Veddah culture is the influence of the communities they were living among. The language they speak is a good example. “Tamil is the language we speak now. Veddah language is very similar to Sinhalese. There are only a few differences.” The Seligmans’ and other researchers after them, recorded that the language of the coastal veddhas resembles Sinhalese. But it is something which is hardly used among the present Coastal Veddah generations. Though he could speak fluently in all three languages, the Vedda language, Tamil and Sinhalese, Velayudan is concerned that the vedda language will die with the passing away of his generation.

So are the vedda religious practices. Though the community had sustained an attack of ‘British religious practices’ thrust upon them decades ago, now it worships both the Hindu gods and their ancestral gods, according to Velayudan. “When our ancestors stopped worshiping the ancestral gods, they inflicted sickness upon them. Even medication could not heal people and they had been dying in great numbers. Then some elders had made a vow to our ancestral gods. That had brought in healing and the British authorities had left us to worship our own gods. Many worship Hindu gods at present, but we celebrate our ancestral gods as well. In the seventh month of each year, with many dances and chanting we pray to our ancestral gods, as we have done for centuries before,” says Velayudan. The village has a small Kovil for the worship of ancestral gods.

Education is another change in their lifestyle. Though Velayudan had never gone to school, today it is a must for his grandchildren. Velayudan welcomes this change and is concerned about the dearth of teachers in the Madurankulam Government School, where most of the village children attend.

Education, had changed employment prospects as well. Most of the coastal veddhas of Kunjankulam still follow their ancestral paths when it comes to employment. They engage in collecting bees’ honey; freshwater fishing and cultivation. The younger generations have changed from these to providing labour and working in garment factories. “Sometimes people from Colombo factories also come here in search of factory workers,” says Velayudan.

Health facilities are not much for those living in their village. Once a month, a doctor from Batticaloa attends the Medical Clinic in the village. On any other day, they have to go to the hospitals in Vakarai or Valachchinai to get medical attention. However, there is only one bus operating in and out of the village, leaving in the morning and returning from Valachchinai in the afternoon.

As socio-economic development reaches the borders of these villages, “Some of the modern coastal veddas, don’t want to say that they are from our tribe. They identify themselves as Tamil,” Velayudan is passionate about their identity.

“Even the authorities now register us as Tamil, in our birth certificates. Those days we were registered as Sri Lankan Veder. We have had discussions with authorities in Colombo, about this problem,” says Velayudan.

It had been in 2011 that Velayudan became the Leader of the Coastal Veddas, taking the mantle from his uncle, Kannamuththu Sellathamby. Aged and ailing, we found him fast asleep, on the bare ground in front of his house.

Never having registered his birth, he is not aware of his age. “When we were in Mankerny I went fishing, even in the sea with fishing nets and cultivated chenas. Now, I can’t walk. So, I transferred my leadership to my nephew. Our generation is dwindling now. We used to hunt samber, deer and porcupine for food those days. I remember visiting the Presiden’t house in Colombo once to meet him,” says the former Veddah leader. Kannamuththu is well versed in vedda folk lore and song. Together with Paththan Chellaiah, he treated us to a few folk songs.

‘The Veddas’ mention many village names of the coastal veddas, Kandalady being one of them. It was not difficult to find the village, situated right opposite the Vakarai bus depot. However, the community therein did not seem to have integrated with the buzz of life emanating from a developing city. The contrast from Kunjankulam was visible in their behaviour as well as lifestyle.

Little children played tag. Women squatted here and there, on the sandy soil. Their physical features bearing a stronger resemblance to the veddas of yore.

Visitors are eyed with suspicion. Some women attempted to hide young girls and children from our sight. We approached an old man, surrounded by a few children. Kandaiyah Thambimuttu told us they were settlers of Thambarakulam, for generations and settled in Kandalady after the tsunami. “I had seven children and lost three of them to the tsunami,” says Kandaiyah remembering there were over 200 families with them in Thambarakulam.

School may not be an option for the children though adults claim they attend school. Kandaiya’s granddaughter had left school after grade 5, to take care of her grandfather. From behind a tree, with only half her face visible she greets us with a shy smile saying she doesn’t like school. Leftovers in an almost empty pot of rice lying right at the door of a very small house, was evidence that they had had a meal of rice the previous night. Need was all around us.

Giving her house to her daughter’s family Chinnathangatchi had moved in to a hut built in the same compound. They earn a pittance from collecting yams of hathawariya (an asparagus species) and selling to the traders at Rs. 150 a kilo, thatching coconut fronds, fishing and collecting prawns, she says. The income is never reliable. We engage in different jobs during different seasons, as labourers.

There are times that we don’t get any work. We do survive, having just one meal a day,” Chinnathangatchi laments. Though many a politician had promised much, any of it is yet to materialise, she comments.

It was Pattiyachenai, in the coastal belt of Kalkudah, we trekked into next, in search of Coastal Veddas. The first inhabitant we met, Thiyagarajah was of the colour of ebony, his bone structure and physical features giving away his identity.

“From the time of our ancestors we have been living in Pattiyachenai,” says Thiyagarajah. These seafarers have been involved in ‘ma del’ fishing. A mixed village about 40 families of the Coastal Vedda tribe live there. They want to preserve their ‘indigenous’ identity. “Some think that Veddahs are only those who live inland, but we belong to the same community,” says Thiyagarajah.

His neighbour Nahan Velupillai joins in the conversation, remembering the times before the civil war when they went fishing together with both the Sinhalese and Tamil communities during the season.

“The war changed everything. They went back to their villages and we went back in to the forest. Now, after the war, we are renewing our contacts,” says Nahan. His daughter is married to a Sinhalese but what does not change is the Vedda identity, though younger generations opt for intermarriage with other communities. Until the time of the tsunami, they had not changed their way of life much, they say. The only change was the huts they had been living in been replaced with 17 houses, by the government, decades back. “Except one house all the others were destroyed by the tsunami. We had been compensated with Rs. 2 lakhs each by the government afterwards. Later, we built some houses adding our savings to that amount. Our children started schooling. Now our grandchildren have gone a step further, however, no one had had a government job,” says Nahan.

As Neminathan, Thiyagarajah’s son joins us, it is evident how much they want to hold onto their identity as indigenous people. “We cannot let our tribal identity die off. We are the ones who can contribute to its future existence.

Though we didn’t understand the importance of our identity when we were young, I often think of it now. We like the Veder identity. I cannot vouch for the future generations. We don’t know whether they would go for mixed marriages and lose our identity. But my message to them would be to do everything possible to protect our identity as indigenous people of this country,” comments Neminathan. His wife is from Kunjankulam, a relative of the Vedda Chief.

The young generations suffering from unemployment is a major problem they face, according to Neminathan. “If one is to get some form of employment he or she has to go behind politicians. We don’t want to do that, so we engage in the traditional forms of income earning passed from generation to generation.” However, with development fast encroaching on their tribal traditions, options are limited.

Coastal Veddas do not have any opportunity to get together and celebrate their indigenous identity. “We do not get together even at the occasion of appointing a leader for our tribe,” they complain. The leadership is announced through messengers after appointment.

The Coastal Veddah population of today, suffer from limited access to facilities and services. Their needs and wants are different from that of the communities they are transplanted into.

They hold on dearly to their tribal identity. It is an important identity as the indigenous Veddah community in the country is already regarded as ‘endangered’. Unless relevant authorities take necessary steps to uphold their identity and the traditional ways which they hang on to, their trail would vanish soon, never to return.