Part 16

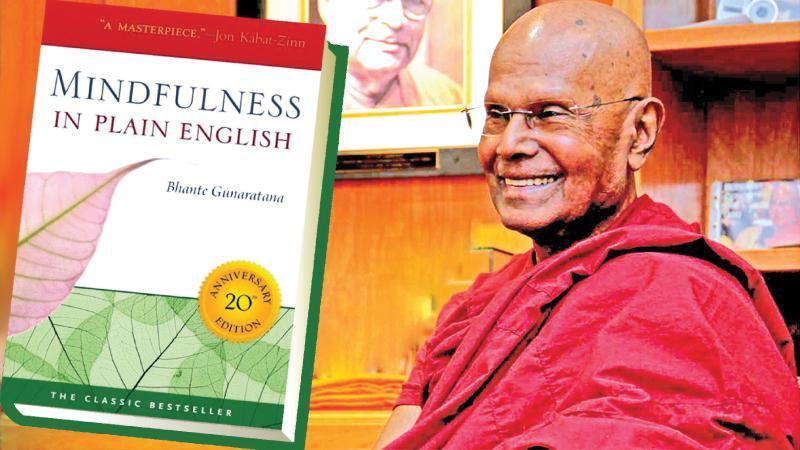

Extracted from renowned meditation guru Bhante Henepola Gunaratana’s Mindfulness in Plain English. The full text of the book will be carried in the Sunday Observer in installments.

Continued from last week

Desire

Let us suppose you have been distracted by some nice experience in meditation. It could be a pleasant fantasy or a thought of pride. It might be a feeling of selfesteem.

It might be a thought of love or even the physical sensation of bliss that comes with the meditation experience itself. Whatever it is, what follows is the state of desire—desire to obtain whatever you have been thinking about, or desire to prolong the experience you are having. No matter what its nature, you should handle desire in the following manner. Notice the thought or sensation as it arises. Notice the mental state of desire that accompanies it as a separate thing.

Notice the exact extent or degree of that desire. Then notice how long it lasts and when it finally disappears. When you have done that, return your attention to breathing.

Aversion

Suppose that you have been distracted by some negative experience. It could be something you fear or some nagging worry. It might be guilt or depression or pain. Whatever the actual substance of the thought or sensation, you find yourself rejecting or repressing—trying to avoid it, resist it, or deny it. The handling here is essentially the same. Watch the arising of the thought or sensation. Notice the state of rejection that comes with it. Gauge the extent or degree of that rejection. See how long it lasts and when it fades away. Then return your attention to your breath.

Lethargy

Lethargy comes in various grades and intensities, ranging from slight drowsiness to utter torpor. We are talking about a mental state here, not a physical one. Sleepiness or physical fatigue is something quite different and, in the Buddhist system of classification, it would be categorised as a physical feeling. Mental lethargy is closely related to aversion in that it is one of the mind’s clever little ways of avoiding those issues it finds unpleasant. Lethargy is a sort of turn-off of the mental apparatus, a dulling of sensory and cognitive acuity. It is an enforced stupidity pretending to be sleep.

Lethargy comes in various grades and intensities, ranging from slight drowsiness to utter torpor. We are talking about a mental state here, not a physical one. Sleepiness or physical fatigue is something quite different and, in the Buddhist system of classification, it would be categorised as a physical feeling. Mental lethargy is closely related to aversion in that it is one of the mind’s clever little ways of avoiding those issues it finds unpleasant. Lethargy is a sort of turn-off of the mental apparatus, a dulling of sensory and cognitive acuity. It is an enforced stupidity pretending to be sleep.

This can be a tough one to deal with, because its presence is directly contrary to the employment of mindfulness. Lethargy is nearly the reverse of mindfulness. Nevertheless, mindfulness is the cure for this hindrance, too, and the handling is the same. Note the state of drowsiness when it arises, and note its extent or degree. Note when it arises, how long it lasts, and when it passes away.

The only thing special here is the importance of catching the phenomenon early.

You have got to get it right at its conception and apply liberal doses of pure awareness right away. If you let it get a start, its growth will probably outpace your mindfulness power. When lethargy wins, the result is the sinking mind, or even sleep.

Agitation

States of restlessness and worry are expressions of mental agitation. Your mind keeps darting around, refusing to settle on any one thing. You may keep running over and over the same issues. But even here, an unsettled feeling is the predominant component. The mind refuses to settle anywhere. It jumps around constantly. The cure for this condition is the same basic sequence. Restlessness imparts a certain feeling to consciousness. You might call it a flavor or texture.

Whatever you call it, that unsettled feeling is there as a definable characteristic. Look for it. Once you have spotted it, note how much of it is present. Note when it arises. Watch how long it lasts, and see when it fades away. Then return your attention to the breath.

Doubt

Doubt has its own distinct feeling in consciousness. The Pali texts describe it very nicely. It’s the feeling of a man stumbling through a desert and arriving at an unmarked crossroad.

Which road should he take? There is no way to tell. So he just stands there vacillating. One of the common forms this takes in meditation is an inner dialogue something like this: “What am I doing just sitting like this? Am I really getting anything out of this at all? Oh! Sure I am. This is good for me. The book said so. No, that is crazy.

I won’t give up

This is a waste of time. No, I won’t give up. I said I was going to do this, and I am going to do it. Or am I just being stubborn? I don’t know. I just don’t know.” Don’t get stuck in this trap. It is just another hindrance. Another of the mind’s little smoke screens to keep you from actually becoming aware of what is happening. To handle doubt, simply become aware of this mental state of wavering as an object of inspection. Don’t be trapped in it. Back out of it and look at it. See how strong it is. See when it comes and how long it lasts. Then watch it fade away, and go back to the breathing.

This is the general pattern you will use on any distraction that arises. By distraction, remember we mean any mental state that arises to impede your meditation. Some of these are quite subtle. It is useful to list some of the possibilities. The negative states are pretty easy to spot: insecurity, fear, anger, depression, irritation, and frustration.

Craving and desire are a bit more difficult to spot because they can apply to things we normally regard as virtuous or noble. You can experience the desire to perfect yourself. You can feel craving for greater virtue. You can even develop an attachment to the bliss of the meditation experience itself. It is a bit hard to detach yourself from such noble feelings. In the end, though, it is just more greed. It is a desire for gratification and a clever way of ignoring the present moment reality.

Trickiest of all, however, are those really positive mental states that come creeping into your meditation. Happiness, peace, inner contentment, sympathy, and compassion for all beings everywhere. These mental states are so sweet and so benevolent that you can scarcely bear to pry yourself loose from them. It makes you feel like a traitor to humanity. There is no need to feel this way. We are not advising you to reject these states of mind or to become heartless robots.

We merely want you to see them for what they are. They are mental states. They come, and they go. They arise, and they pass away. As you continue your meditation, these states will arise more often. The trick is not to become attached to them. Just see each one as it comes up. See what it is, how strong it is, and how long it lasts. Then watch it drift away. It is all just more of the passing show of your own mental universe.

Just as breathing comes in stages, so do the mental states. Every breath has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Every mental state has a birth, a growth, and a decay. You should strive to see these stages clearly. This is no easy thing to do, however. As we have already noted, every thought and sensation begins first in the unconscious region of the mind and only later rises to consciousness. We generally become aware of such things only after they have arisen in the conscious realm and stayed there for some time. Indeed we usually become aware of distractions only when they have released their hold on us and are already on their way out. It is at this point that we are struck with that sudden realization that we have been somewhere, daydreaming, fantasizing, or whatever. Quite obviously this is far too late in the chain of events. We may call this phenomenon catching the lion by his tail, and it is an unskillful thing to do.

Like confronting a dangerous beast, we must approach mental states head on. Patiently, we will learn to recognize them as they arise from progressively deeper levels of our conscious mind.

Since mental states arise first in the unconscious, to catch the arising of the mental state, you’ve got to extend your awareness down into this unconscious area. That is difficult, because you can’t see what is going on down there, at least not in the same way you see a conscious thought. But you can learn to get a vague sense of movement and to operate by a sort of mental sense of touch. This comes with practice, and the ability is another of the effects of the deep calm of concentration.

Concentration slows down the arising of these mental states and gives you time to feel each one arising out of the unconscious even before you see it in consciousness. Concentration helps you to extend your awareness down into that boiling darkness where thought and sensation begin.

As your concentration deepens, you gain the ability to see thoughts and sensations arising slowly, like separate bubbles, each distinct and with spaces between them. They bubble up in slow motion out of the unconscious. They stay a while in the conscious mind, and then they drift away.

The application of awareness to mental states is a precision operation. This is particularly true of feelings or sensation. It is very easy to overreach the sensation. That is, to add something to it above and beyond what is really there.

It is equally easy to fall short of sensation, to get part of it but not all. The ideal that you are striving for is to experience each mental state fully, exactly the way it is, adding nothing to it and not missing any part of it. Let us use pain in the leg as an example. What is actually there is a pure, flowing sensation. It changes constantly, never the same from one moment to the next. It moves from one location to another, and its intensity surges up and down. Pain is not a thing. It is an event. There should be no concepts tacked on to it and none associated with it. A pure unobstructed awareness of this event will experience it simply as a flowing pattern of energy and nothing more. No thought and no rejection. Just energy.

Early on in our practice of meditation, we need to rethink our underlying assumptions regarding conceptualization. For most of us, we have earned high marks in school and in life for our ability to manipulate mental phenomena, or concepts, logically.

Our careers, much of our success in everyday life, our happy relationships, we view as largely the result of our successful manipulation of concepts. In developing mindfulness, however, we temporarily suspend the conceptualisation process and focus on the pure nature of mental phenomena. During meditation we are seeking to experience the mind at the preconceptual level.

But the human mind conceptualises such occurrences as pain. You find yourself thinking of it as “the pain.” That is a concept. It is a label, something added to the sensation itself. You find yourself building a mental image, a picture of the pain, seeing it as a shape. You may see a diagram of the leg with the pain outlined in some lovely color. This is very creative and terribly entertaining but not what we want. Those are concepts tacked on to the living reality. Most likely, you will probably find yourself thinking: “I have a pain in my leg.” “I” is a concept. It is something extra added to the pure experience.

When you introduce “I” into the process, you are building a conceptual gap between the reality and the awareness viewing that reality. Thoughts such as “me,” “my,” or “mine” have no place in direct awareness. They are extraneous addenda, and insidious ones at that. When you bring “me” into the picture, you are identifying with the pain. That simply adds emphasis to it. If you leave “I” out of the operation, pain is not painful. It is just a pure surging energy flow. It can even be beautiful. If you find “I” insinuating itself in your experience of pain or indeed any other sensation, then just observe that mindfully. Pay bare attention to the phenomenon of personal identification with pain.

The general idea, however, is almost too simple. You want to really see each sensation, whether it is pain, bliss, or boredom. You want to experience that thing fully in its natural and unadulterated form. There is only one way to do this. Your timing has to be precise. Your awareness of each sensation must coordinate exactly with the arising of that sensation. If you catch it just a bit too late, you miss the beginning. You won’t get all of it. If you hang on to any sensation past the time when it has faded away, then what you are holding onto is a memory. The thing itself is gone, and by holding onto that memory, you miss the arising of the next sensation. It is a very delicate operation. You’ve got to cruise along right here in the present, picking things up and letting things drop with no delays whatsoever. It takes a very light touch. Your relation to sensation should never be one of past or future but always of the simple and immediate now.

The human mind seeks to conceptualise phenomena, and it has developed a host of clever ways to do so. Every simple sensation will trigger a burst of conceptual thinking if you give the mind its way. Let us take hearing, for example. You are sitting in meditation and somebody in the next room drops a dish. The sounds strike your ear. Instantly you see a picture of that other room.

You probably see a person dropping a dish, too. If this is a familiar environment, say your own home, you probably will have a 3-D technicolor mind movie of who did the dropping and which dish was dropped. This whole sequence presents itself to consciousness instantly. It just jumps out of the unconscious so bright and clear and compelling that it shoves everything else out of sight. What happens to the original sensation, the pure experience of hearing? It gets lost in the shuffle, completely overwhelmed and forgotten. We miss reality. We enter a world of fantasy.

Here is another example: You are sitting in meditation and a sound strikes your ear. It is just an indistinct noise, sort of a muffled crunch; it could be anything. What happens next will probably be something like this. “What was that? Who did that? Where did that come from? How far away was that? Is it dangerous?” And on and on you go, getting no answers but your fantasy projection.

Conceptualisation is an insidiously clever process. It creeps into your experience, and it simply takes over. When you hear a sound in meditation, pay bare attention to the experience of hearing. That and that only. What is really happening is so utterly simple that we can and do miss it altogether. Sound waves are striking the ear in a certain unique pattern. Those waves are being translated into electrical impulses within the brain, and those impulses present a sound pattern to consciousness. That is all. No pictures. No mind movies. No concepts. No interior dialogues about the question. Just noise. Reality is elegantly simple and unadorned. When you hear a sound, be mindful of the process of hearing. Everything else is just added chatter. Drop it.

This same rule applies to every sensation, every emotion, every experience you may have. Look closely at your own experience. Dig down through the layers of mental bric-abrac and see what is really there. You will be amazed how simple it is, and how beautiful.

There are times when a number of sensations may arise at once. You might have a thought of fear, a squeezing in the stomach, an aching back, and an itch on your left earlobe, all at the same time. Don’t sit there in a quandary.

Don’t keep switching back and forth or wondering what to pick. One of them will be strongest. Just open yourself up, and the most insistent of these phenomena will intrude itself and demand your attention. So give it some attention just long enough to see it fade away. Then return to your breathing. If another one intrudes itself, let it in. When it is done, return to the breathing.

This process can be carried too far, however. Don’t sit there looking for things to be mindful of. Keep your mindfulness on the breath until something else steps in and pulls your attention away. When you feel that happening, don’t fight it.

Let your attention flow naturally over to the distraction, and keep it there until the distraction evaporates. Then return to breathing. Don’t seek out other physical or mental phenomena. Just return to breathing. Let them come to you.

There will be times when you drift off, of course. Even after long practice you find yourself suddenly waking up, realising you have been off the track for some while. Don’t get discouraged. Realise that you have been off the track for such and such a length of time and go back to the breath. There is no need for any negative reaction at all. The very act of realising that you have been off the track is an active awareness. It is an exercise of pure mindfulness all by itself.

Exercise of mindfulness

Mindfulness grows by the exercise of mindfulness. It is like exercising a muscle. Every time you work it, you pump it up just a little. You make it a little stronger. The very fact that you have felt that wake-up sensation means that you have just improved your mindfulness power. That means you win.

Move back to the breathing without regret. However, the regret is a conditioned reflex, and it may come along anyway—another mental habit. If you find yourself getting frustrated, feeling discouraged, or condemning yourself, just observe that with bare attention. It is just another distraction. Give it some attention and watch it fade away, and return to the breath.

The rules we have just reviewed can and should be applied thoroughly to all of your mental states. You are going to find this an utterly ruthless injunction. It is the toughest job that you will ever undertake. You will find yourself relatively willing to apply this technique to certain parts of your experience, and you will find yourself totally unwilling to use it on the other parts.

Meditation is a bit like mental acid. It eats away slowly at whatever you put it on. We humans are very odd beings. We like the taste of certain poisons, and we stubbornly continue to eat them even while they are killing us.

Thoughts to which we are attached are poison. You will find yourself quite eager to dig some thoughts out by the roots while you jealously guard and cherish certain others. That is the human condition.

Vipassana meditation is not a game. Clear awareness is more than a pleasurable pastime. It is a road up and out of the quagmire in which we are all stuck, the swamp of our own desires and aversions. It is relatively easy to apply awareness to the nastier aspects of your existence. Once you have seen fear and depression evaporate under the hot, intense beacon of awareness, you will want to repeat that process. Those are the unpleasant mental states.

They hurt. You want to get rid of those things because they bother you. It is a good deal harder to apply that same process to mental states that you cherish, like patriotism, or parental protectiveness, or true love. But it is just as necessary. Positive attachments hold you in the mud just as assuredly as negative attachments. You may rise above the mud far enough to breathe a bit more easily if you practices Vipassana meditation with diligence. Vipassana meditation is the road to Nibbana. And from the reports of those who have toiled their way to that lofty goal, it is well worth every effort involved.

To be continued