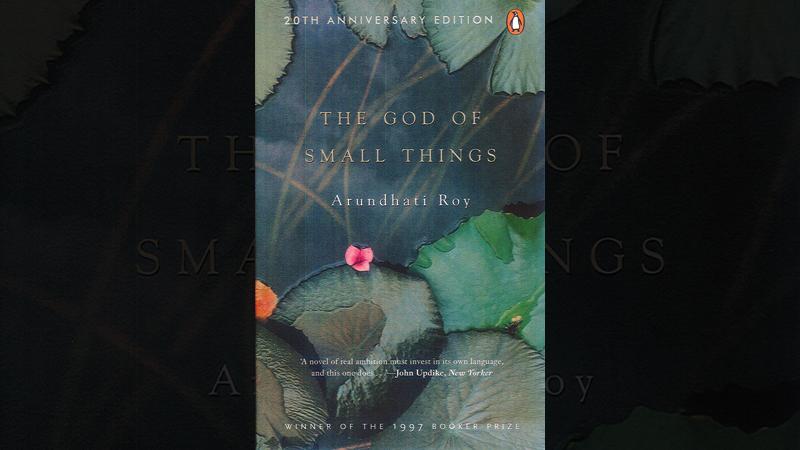

Book: God of Small Things

Author: Arundhati Roy

Publisher: Penguin Random House

In the first chapter titled ‘Paradise pickle and preserves of god of small things’, Arundhati Roy begins the story as follows: “May in Ayemenem is a hot, brooding month. The days are long and humid, the river shrinks and black crows gorge on bright mangoes in still dust green trees. Red bananas ripen and jak fruits burst. Dissolute blue bottles hum vacuously in the fruity air. Then they stun themselves against clear windowpanes and die, fatly baffled in the sun. The nights are clear but suffused with sloth and sullen expectation.” The opening passage is enough for a reader what to expect from the author.

The book keeps sailing even though some readers might need to resist the temptation of jumping overboard for a pause. At Rachel’s grandmother’s pickle factory, paradise pickles and preserves, the banana jam made illegally was neither jam not jelly. It was too thin for jelly and too thick for jam – an ambiguous unclassifiable consistency. Much like her family which had difficulty with classification, it ran much deeper than the ‘jam jelly question.’

There is no difficulty in classifying Arundhati Roy’s debut novel The God of Small Things as a modern-day classic. Her betrayal of family, class and caste led to comparison with William Faulkner. Her acute observation of society reminded readers of Charles Dickens and her magical words of Salman Rushdie and Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Not old, not young

When Rachel came back to Ayemenem in June, it was raining. “Slanting silver ropes slammed into loose earth, ploughing it up like gunfire.” She was 31 years old, “Not old, not young, but a viable, dieableage.” She returns to Ayemenem house for her twin brother, Esthappen or Estha who she hadn’t seen in 25 years – the ‘unidentical two-leg twins. Not since 1967, when their cousin Sophie Mol drowned in the river and when the police found Velutha.

“Memories of tragedies of a time when the unthinkable became thinkable and the impossible really happened” come flooding back to Rachel. She remembers her mother Ammu who died at 31; her brother Estha, the quiet boy who stopped talking one day.

“ … in those early years … Rachel thought of themselves together as me and separately, individually, as we or us. As though they were a rare breed of Siamese twins, physically separate, but with joint identities” and the extended family of Ayemenem House, especially her elegant grandmother Mammachi, her uncle Chacko, his English wife Margaret Kochamma and her grand aunt Baby Kochamma.

All in the family had broken rules, crossed into forbidden territory, tampered with the laws that lay down who should be loved and how, and would have to pay, as the narrator says, “Perhaps it’s true that things can change in a day. That a few dozen hours can affect the outcome of whole lifetimes and that when they do, those few dozen hours, like the salvaged remains of a burned house – the charred clock, the singed photograph, the scorched furniture – must be resurrected from the ruins and examined, preserved, accounted for.”

Lost in a dream

In its 340 pages we need all of them as they are ‘preserved, accounted for like Velutha, the other the God of Loss, the God of Small Things. In the eponymous chapter Ammu is lost in a dream and her children wonder whether they should wake her up. “You looked so sad,” Estha said, “I was happy,” Ammu replied. “If you are happy in a dream Ammu, does that count?” Estha asks, “The happiness – does it count?” And Ammu knew exactly what he meant. “If you eat fish in a dream, does it count? Does it mean you’ve eaten fish?”

In the end, historical and social pressures, the impossible rigidity of the caste system, for instance, tell on the love and longing of the Ayemenem householders. The author won the Booker Prize for the novel. The God of Small Things is an excellent novel. It has been hailed by the mainstream lineage in Anglophone writing – those many children of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens – though in Roy’s case, thankfully midwifed by John Berger, it spins a tale of individuals in a colourfully post-colonial setting, along well-established lines of Anglophone novel writing, sometimes brushed with magic, behind which lurked the politics of its author.

One can claim with some justice that The God of Small Things used standard fictional props to suck in the global-liberal reader, before inserting uncomfortable slivers of doubt into his world view. This would be a partial defence and it would leave some things unanswered. For instance, can caste oppression be fully narrated through the moving tragedy of a Dalit (lower caste) whose perfect body has escaped the punishing marks of centuries of deprivation, or can incest be presented as a radical resolution but then not narrated further as the socially and psychically combustive matter that it also is?

Compulsive surge

One of the reasons the novel succeeded despite everything else is Roy’s talent at literally painting with words. At her best she can make the light of language illuminate dense material reality in ways few writers can match. Another of Roy’s strength which makes her a better writer than many others is her ability to empathise across some differences. This is in full flow in the novel despite its often compulsive surge in predetermined directions and of course, empathy is essential not just for creativity but also for our fragile humanity. This is what makes the novel and its writer significant.

The God of Small Things is a sad story told very hilariously, tenderly and craftily. The Daily Telegraph said, “It is rare to find a book that so effectively cuts through the clothes of nationality, caste and religion to reveal the bare bones of humanity.” The well-known author William Dalrymple hailed the novel as a masterpiece, utterly exceptional in every way.