As a contribution to national peace building, we feature below individual efforts of literary activists of Sri Lanka to preserve, promote and use the languages of Sinhala and Tamil as tools of understanding, empathy and compassion.

Hemachandra Pathirana

This is the story of Hemachandra Pathirana, a 59-year-old who is ethnically a Sinhalese and functions as a translator at a Sri Lankan State bank. He has spent his life mastering all three languages at senior academic level. He has used his knowledge as a teacher of language and to translate literary works published in Sinhala and Tamil.

He has translated works of different Sri Lankan writers focusing on diverse communities in the island, and in different geographical pockets not receiving much attention, such as the Muslims in the South, the Indian origin Tamils in the tea plantations and Sinhalese language poetry as well as literature that weave a gamut of life experiences of the Sinhalese people and presenting them in Tamil.

Below is his narrative in his words:

“My father had grown up in Bingiriya close to Kurunegala that had a significant composition of (Tamil speaking) Muslims. His playmates were Muslims. I had no such luck. Although I loved languages as a child, I did not learn Tamil from my father and nor did I have childhood friends to speak the language with.”

“I began to self-learn Tamil in my late teens. However, it is around the age of 30 that I started on a Master’s Degree in the Tamil language. Since then I have functioned as a language teacher of Tamil and Sinhala as well as a translator of literary works published in Sinhala and Tamil.”

“I began to self-learn Tamil in my late teens. However, it is around the age of 30 that I started on a Master’s Degree in the Tamil language. Since then I have functioned as a language teacher of Tamil and Sinhala as well as a translator of literary works published in Sinhala and Tamil.”

“When you teach those learning language as a second language, it is a challenge. This could be well understood by someone like me who self-learnt the art of learning Tamil as a second language and obtained an MA in the Tamil Language and Literature.”

“As a translator of literary works, I chose work based on Sinhala, Muslim and Tamil communities. While some of the works are about difficult times, some are about the many beautiful interactions between the two communities that often do not get into the media.

“Some are on accounts of great trauma, stress that occurred between 1983 and 2009, portrayed through short stories and novels. My ability to understand Tamil helped me understand through literature social perspectives concerning the Tamils and Muslims that I may not have understood till then.”

“I was 23 years old and the first book I read was by Dikwella Kamal. The title was Viduthalai (Freedom) and the stories revolved around the Muslim community in general and covering Muslim societal narratives from around Sri Lanka.

A collection of his short stories was the first book I translated titled ‘Kandulaka Kathawak’. Dikwella Kamal had created a niche for himself by creating stories from the Muslim culture that evolved in the South which is different from other regions of Sri Lanka.

For example, he wrote much about the Muslims of Dikwella. The other book that had a major impact on me when I read it and when I undertook to translate it was about the humanitarian service in the North carried out by the renowned bhikkhu Ven. Madihe Pangnaseeha, who 54 years ago started building four schools for low caste children in the North.

The Sinhala book authored by Sinhala language writer Denagama Siriwardena was titled Uthurata Senehasa Pe Dakune Maha Yathiwarayano (The great bhikkhu who cared for the North). The book was translated by me some time back and the Tamil title is Vadakkei Nesiththa Thetkin Thuravi.

The book by Denagama Siriwardena narrates this humanistic bhikkhu’s attitude to Tamil children in far flung areas in the Jaffna district and as the chapters unfold, one gets to the story of the Tamil Vidyalaya in Puttur that was built by him and known as the Puttur Madihe Panchaseeha Tamil Maha Vidyalaya.”

“This school and another built by him are functioning to date.

“I was greatly moved by the last book I translated by Sri Lankan Tamil author Dr. T. Gnanasekeran titled Uthura Ginigani in Sinhala and Erimalai (Volcano) in Tamil, written and based around the time of 1984.

“This story revolves around a medical doctor and his family as well as close interaction with a Sinhalese family has stayed with me very strongly. It was an emotional moment to see the book I translated launched in November.“

“I believe that if we bridge the language gap, we can heal many wounds of the past this nation has seen and link ethnic communities together as in one family. Knowledge of any language is a social asset.”

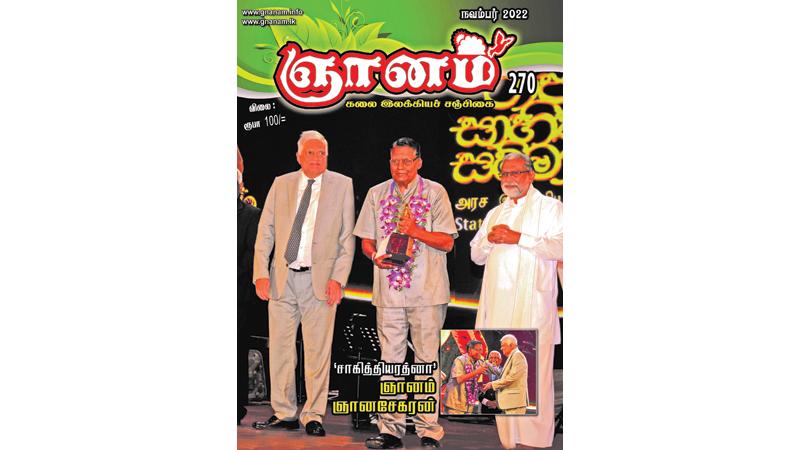

Dr. T. Gnanasekaran

Dr. T Gnanasekaran received the “Sahitya Ratna” Lifetime Award at the State Literary Awards this year. He has dedicated his life to healing persons through his medical profession and healing through the literary word.

Below is his narrative.

“In my life which spans eight decades I have dedicated myself to the literary world. To understand a very difficult chapter in recent Sri Lankan history, I started my novel Eramalai in 1984, when the citizens of Jaffna thought the battle between the newly formed LTTE and the security forces were an aberration which would pass and life restored to the peaceful Jaffna we knew.”

“By profession, I am a registered medical practitioner, a three-year qualification almost similar to that of a medical doctor and granted then from the Medical College. We were licensed medical practitioners and were referred to as doctors.”

“For a significant part of my working life, I worked in the plantation community. For much of my life, I lived among the Sinhalese. Kandy was my base. I worked a lot at Pusselawa, Nawalapitiya and many adjacent plantation areas. Living in Kandy helped me travel to those locations. Although I live in Colombo now, I still have my house in Kandy.”

“For a significant part of my working life, I worked in the plantation community. For much of my life, I lived among the Sinhalese. Kandy was my base. I worked a lot at Pusselawa, Nawalapitiya and many adjacent plantation areas. Living in Kandy helped me travel to those locations. Although I live in Colombo now, I still have my house in Kandy.”

“Writing was something I was continuing since childhood. As my life experience in Sri Lanka increased, based on my interaction with all communities of the country, I began to think deeply about the social divides that were forming. I began to write attempting to understand, from different perspectives, each situation that different people of Sri Lanka faced.”

“I attempted to look at issues we faced, especially what is referred to as the ‘ethnic issue’ objectively. This I did primarily through my novel ‘Eramalai’ which was translated to English by V. Thillainathan titled as ‘Volcano’ and into Sinhala translated by Hemachandra Pathiranatitled as Uthura Gini Gani. The Sinhala version of the book was launched recently.”

“My collection of short stories titled Alsation Punakutiyam which covers short stories from around the country has been taught for the past 22 years under the BA degree syllabus of the Sabaragamuwa University. The short stories cover different ethnic and religious communities in the country and different geographical locations such as Colombo, Jaffna and Kandy.

“My novels include one on estate life titled Kuridi Malai (Blood Mountain) on the hardships of the tea plantation community and Puhiya Suvadal (new steps) about the caste system among Tamils of Sri Lanka.”

“Twenty years ago, I started the Tamil literary magazine ‘Gnanam; published from Colombo in print and electronic forms. In this, we give space to writers from around the world who write on Tamil literature and we also give space to introduce Sinhala authors to the Tami readership.

“Over the years, we have introduced several Sinhala authors to the Tamil readership, especially Sinhala literary legends such as Martin Wickremesinghe and Gunadasa Amarasekara. We hope to introduce more Sinhala writers of the younger generation.

“We are printing the literary magazine at a loss. Since our mission is to contribute to literature and teach human beings to create empathy and understanding, we continue even in this challenging economic context where we have a great reduction in advertisers. We send the PDF version free to 10,000 readers worldwide.”

Nakiyadeniye G. Wijesekera (Nanayakkara Wasam Hapugalage Gunadasa Wijesekera)

Ethnically a Sinhalese, he is 70-years-old and self-taught in Tamil. He uses this language skill to write poetry about the need for humanity to be more empathetic and focuses significantly on the Plantation Tamil community who he grew up amongst. He is one of the few Sinhala poets writing in Tamil. Many of the poems have parallel Sinhala versions. Overall, his poems capture the difficulties of the working class.

One of his poems speaks of the difficulties of surviving on a meagre salary and is titled Komepittuwa.

The poem describes the vanishing nature of the salary of a labourer who toils for a pittance. Surrounded by life’s glittering needs and wants the salary rises like a giant komepittuwa (sand structure) only to perish in no time. The metaphor used for the meagre salary is the sand made pyramid like structure which is a komepittuwa (Sinhala wording) that children make on the beach and the cost of living is equated to the high Himalayas.

Below is his narrative

“I grew up at Lindula, Nuwara Eliya; an area inhabited by the plantation community. My first teacher in the Tamil language was a wise, 13-year-old child, about two years younger than me, who was from Indian Tamil origin. Her family ran a small grocery store. I had left school to earn a living and worked close to their home.

“She took upon herself the task of teaching me Tamil. Where ethnicity was concerned, I was a Sinhalese and she was a Tamil who did not have citizenship in the country but we never felt this gap. We were children untainted by the adult world.”

“Word by word she taught me. I wrote them down in an old exercise book. Later, I used the knowledge of this language to write poetry, long after she was gone.”

“I have lived among people who laboured upon the land; the tea growers and the rubber tappers. I have written innumerable poems about these communities. The milk they tapped from the trees was the sustenance for their family. I saw this as the milk of mother earth.”

“Look at what you see everywhere. Human beings are used. Money is worshipped. If I could get people to think deeply, after reading some of my poems, I would be happy. We are machines today. We do not think.”

“Writing about these things is not enough. We need people to carry out actions of love transformed into national policy to prevent exploitation. Imagine if all those who were in powerful worldly positions did this?”

“After my young teacher left for India, I searched out different words in old newspapers, magazines and books to continue to learn this language. The Tamil language used in my poetry is simple and not what one would call ‘literary.’ But the reception my works have received in the Tamil press has encouraged me to write more, dedicating my poetry promoting human values. Most of the poems are published with the Sinhala translation.

“I have collated many of my early poems in my book titled Wijeya Sihinaya (the dream of Wijeya), published in 2011. The concept of Sihinaya or dream is related to my vision of creating a more compassionate world.

“I have now completed a new manuscript that has a collection of poems written in the past few years and currently struggling with the rising printing costs.

“The Tamil title of my latest book is Ninevellam Unvasam and can be loosely translated as ‘all thoughts hold the scent of love and humanity’ although the direct translation means ‘all thoughts hold the scent of you.’ The ‘you’ here is a direct reference to the reader to address the humanity within himself or herself to view the world.

“At another level, it could also be seen as a set of love poems. I work in an estate and earn a simple salary. I have dedicated my life to the task of linking human beings through poetry through the languages of Sinhala and Tamil used parallel not because any organisation or persons tell me to do so, but because my heart tells me to.”

“I think it is every human being’s task to bring about peace in the world he or she is born to. I have travelled several times to the North and each time I have written poetry on my interaction with the people there.”

“We need to uphold our own language, religion and culture and appreciate those of others. But none of us should have an Umathuwa (Madness) about it. It is this madness that makes this world mad. This is what we can refer to as racism or religious fanaticism which is the downfall of humans.”

“I am currently working in the Galle district where I live with my family.”

“I travel freely in the North and the East. If I did not know the Tamil language, I would not be able to do this. In Sri Lanka, we use three languages and although I do not know English, learning Tamil helped me communicate and understand many people in the country.