“People who were educated in British schools and who were taught European history and geography, neglecting native history and geography cannot see the true value of their country’s past which they view with the eyes of the foreigners.” – Ivan Minayev

On May 23, 2012 the Institute of Philosophy, Russian Academy of Sciences released the 1,045 page- Encyclopedia of Buddhism edited by Dr. Marietta Stepanyants. The event took place in the presence of scholars from France, India, Iran, Japan, Lithuania, Russia, Syria, Turkey, UK, and USA, who were participating in the Third International Conference on Comparative Philosophy: ‘Philosophy and Science in the Cultures of East and West’ organised by the Institute of Philosophy in Moscow.

On May 23, 2012 the Institute of Philosophy, Russian Academy of Sciences released the 1,045 page- Encyclopedia of Buddhism edited by Dr. Marietta Stepanyants. The event took place in the presence of scholars from France, India, Iran, Japan, Lithuania, Russia, Syria, Turkey, UK, and USA, who were participating in the Third International Conference on Comparative Philosophy: ‘Philosophy and Science in the Cultures of East and West’ organised by the Institute of Philosophy in Moscow.

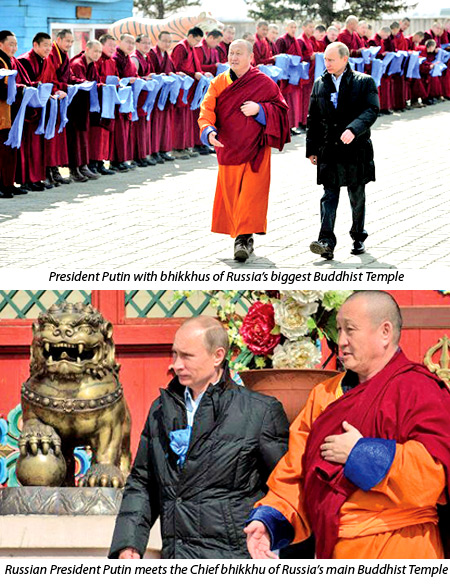

On August 24, 2009 Russian Buddhists received political acknowledgement when the then President (later Prime Minister) Dmitry Medvedev announced his support for Buddhism’s revival during a visit to Buryatia, Siberia. Addressing Russian Buddhists at the Ivolga Datsan Monastery, he said (as reported in the American Buddhist journal Tricycle):

“Russia is in a special position in the sense that it is the only European country that recognises Buddhism as one of the traditional religions. One of the world’s oldest, it has been practised for over three centuries by Buryats, Kalmyks, Tuvans and other peoples native to this country, Buddhism’s philosophy and spiritual practice have had a deep-reaching influence on the customs and traditions of all those who live here and all those who follow this religion. Of course, the unique Buddhist culture is an integral and greatly valued part of Russia’s common historical and cultural heritage.”

“Russia is in a special position in the sense that it is the only European country that recognises Buddhism as one of the traditional religions. One of the world’s oldest, it has been practised for over three centuries by Buryats, Kalmyks, Tuvans and other peoples native to this country, Buddhism’s philosophy and spiritual practice have had a deep-reaching influence on the customs and traditions of all those who live here and all those who follow this religion. Of course, the unique Buddhist culture is an integral and greatly valued part of Russia’s common historical and cultural heritage.”

Buddhism was incorporated into Russian society 17th century when the Kalmyk people travelled to and settled in Siberia which is now the Russian Far East. Russia’s main form of Buddhism is Tibetan Buddhism which spread into Mongolia and via Mongolia into Russia.

Russian scholars and academics

The introduction of this religion to the country generated an interest in the subject among Russian scholars and academics. There have been Slavic Russian converts to Buddhism since the 19th century. But, it is only after 1990 that real growth of Slavic converts to Buddhism began. They are based in the large cities such as Moscow and St. Petersburg where there is greater access to urban Buddhist centres and facilities.

Although religious practices were suppressed in former Soviet Russia under communist rule, especially under Stalin’s dictatorship, academic interest in different civilisations and cultures was renewed after Stalin’s death. This included the study of Buddhist philosophy and culture and their role in Russia’s relations with Asian countries, including Sri Lanka.

The journalistic notes by Vladimir Yakovlev, Russian diplomat and the first Soviet Ambassador in Sri Lanka give a good insight to this. He had taken the decision to write them since very few Sri Lankans remembered his compatriots who had acquainted Russia with this island.

Among the first Russians to visit Sri Lanka was Ivan Minayev, a prominent 19th Century Buddhist scholar whose name ranks with the founders of the Russian school of ‘Buddhalogy’ as they called it. Among his pupils were leading Orientalists S.F. Oldenburg and F.I Shcherbatskoy who wrote the two-volume Buddhist Logic. Sri Lankan bhikkhus showed a copy of this important work in a library to Ambassador Yakovlev, after his arrival in Sri Lanka in April 1957.

Among those who helped the Soviet Government to establish a Buddhist studies section at the Moscow University was Sri Lanka’s first Ambassador to the USSR, Professor Gunapala Malalasekera after Nikita Khrushchev became Prime Minister.

Cultural and historical development

Minayev also wrote, Buddhism, Research and Documents published in 1887. The total number of works he published is 130, according to Yakovlev. The latter quotes Soviet Orientalist G.M. Bongard-Levin as saying that Minayev understood and always emphasised the great role of Buddhism in the cultural and historical development of the Orient and widely used Buddhist documents in his studies of folk-lore, literature, ethnography, religion and languages.

Minayev knew many languages including Sanskrit and Pali which enabled him to analyse archive papers in European libraries. He was, however, not an armchair scholar, but was willing to experience Buddhism in practice -first of all, Theravada. Between 1874 and 1877, he made several lengthy trips to Sri Lanka, India, Nepal and Myanmar. Before coming to Sri Lanka, Minayev had made a thorough study of the ancient Sinhala chronicles, Deepavansa and Mahawansa.

Minayev knew many languages including Sanskrit and Pali which enabled him to analyse archive papers in European libraries. He was, however, not an armchair scholar, but was willing to experience Buddhism in practice -first of all, Theravada. Between 1874 and 1877, he made several lengthy trips to Sri Lanka, India, Nepal and Myanmar. Before coming to Sri Lanka, Minayev had made a thorough study of the ancient Sinhala chronicles, Deepavansa and Mahawansa.

Minayev’s critical attitude to Britain’s colonial policy in Sri Lanka runs through his entire description of the country’s political and social life. His righteous approach and protest against colonial oppression are clearly expressed in his articles and books.

Minayev did not stay long in Colombo after arriving in Sri Lanka on July 18, 1874. He was anxious to see the places where Buddhism emerged in this ancient land and the country’s national culture originated – above all the island’s former capitals of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa. He travelled all the way to by foot and by cart to examine the ruins of temples and palaces, unscrambled ancient inscriptions and made sketches of architectural monuments and wall paintings in his diaries.

He wrote: “Those historical relics were a live book of intellectual and spiritual life of the ancient people.”

Majestic structures

Minayev used Buddhist chronicles to re-create the appearance of the majestic structures the ancient architects had built. He wrote that the various images on the huge granite plates, columns and cornices were “evidence of what these people believed in whom they prayed to, how rich the ancestors of the Sinhalese of today were and the elegance and good taste with which they surrounded their life.”

It needs to be emphasised that when he wrote this, he was well acquainted with such masterpieces of ancient architecture and art as the stone sculptures of Ellora and the immortal creations of anonymous artists in the Ajanta caves of India. He stressed the originality and national uniqueness of the art of ancient Sri Lankans.

“Nowhere else in the world will you find anything like the monuments of the past in Ceylon, either in design or execution” wrote Minayev. He studied the country meticulously, starting with its ancient history. To the East of Matara, sprawled the ancient kingdom of Ruhuna. Minayev studied in detail the surviving monuments of that once flourishing land. Walking about the ruins, he determined and wrote down the dimensions of the once magnificent stupas and temples and made their exact sketches.

From Hambantota, he returned to Colombo where he put up at the Oriental Hotel (GOH) a place where only Europeans lived at the time. Minayev felt disgusted with the racism of the hotel management. He wrote “Not a single coloured person is allowed in the hotel, where Europeans live.”

He said, “In Ceylon, the British are not only rulers but also elite people of a higher race, who have nothing in common with the coloured people. The natives feel this and such attitude of the rulers to their motherland does not stir any sympathy in their hearts of course.”

He visited Kandy several times and stressed in his notes that the Kandyan state encircled by the jungle and mountain ranges was the last bulwark of the Sinhalese people’s independence.

Leading bhikkhus

According to Yakovlev, Minayev would often live in ordinary cells of the bhikkhus, many of whom became his friends. In his diaries, he wrote on such leading bhikkhus as the Ven. Hikkaduwe Sri Sumangala Thera, Ven. Migettuwatte Sri Gunananda Thera (the brilliant orator whose polemical skills in the Panadura Buddhist-Christian debate of 1873 drew the attention of Col. Henry S. Olcott) and Ven. Battaramulle Subhoothi Thera with whom Minayev exchanged letters after his return to Russia. Minayev called Ven, Subhoothi Thera, “the most learned of the Sinhalese.”

In 1873 Ven. Subhoothi Thera founded the Vidyodaya Pirivena which later became a University. He was also the only teacher of the pirivena which was attended by 45 bhikkhus and 12 laymen at the time.

Everything Minayev wrote about Sri Lanka and her Buddhist heritage was new and attracted the attention of the Russian readers. He often noted the monks’ cordial hospitality.

“They are very open-minded. Never shun Europeans and never hide their sacred relics or books from the newcomer. They are very complaisant and willingly show all the things of interest in the monasteries.”

At the same time, Minayev noted with sorrow that a section of the population worshiped everything related to the British culture.

“People who were educated in British schools and who were taught European history and geography, neglecting native History and Geography cannot see the true value of their country’s past which they view with the eyes of the foreigners.”

The Russian scholar noted that people got anglicised unconsciously and many of them thought that patriotism is identical with wearing a sarong!