Sports are filled with true-life fairy tales, stories that are more incredible than fiction. But even accepting that premise, the rise of Robert Bruce Mathias almost challenges belief. Affectionately, known as “Bob,” he was an American decathlete, two-time Olympic gold medallist, a United States Marine Corps officer, actor and United States Congressman representing California.

Winning the Olympic decathlon title is one of the most demanding challenges in sport. Defending the Olympic title has remained beyond the dreams of all but a tiny handful of athletes. Doing so requires the ability to maintain incredible levels of technique, strength and stamina. Staying fit and healthy is often the hardest part of the challenge.

Bob Mathias had never competed in a decathlon before 1948. Yet, 17-year Mathias, proved a prodigiously good choice, revelling in the challenge of the multiple disciplines and the hard work that the sport demanded. Less than three months after the idea was first put to him, he qualified for the United States Olympic team for London 1948 Olympic Games.

Birth and Progression

Robert Bruce Mathias was born to Dr. Charles and Lillian Mathias on November 17, 1930

in Tulare, California, United States. He was the second of the four children and his siblings were his older brother Eugene, younger brother James, and younger sister Patricia. Dr. Charles Mathias served at the University of Oklahoma and encouraged his children to participate in sports.

When Mathias was 11, he was found to have a shortage of red blood cells, and his father treated him for anaemia. He had to take iron pills, eat a special diet, and take frequent naps to conserve his strength just to get through the day. He paid careful attention to his diet in an effort to get stronger. One way or another, it all worked.

By the time he entered Tulare High School, he had recovered from this illness. As a high school student, he took part in basketball, football and athletics, he was a star in every event he participated. As a senior, he won two California high school championships in the hurdles and was placed fourth in the shot put.

By the time he entered Tulare High School, he had recovered from this illness. As a high school student, he took part in basketball, football and athletics, he was a star in every event he participated. As a senior, he won two California high school championships in the hurdles and was placed fourth in the shot put.

While at Tulare Union in early 1948, Mathias took up the decathlon at the suggestion of his track coach, Virgil Jackson. He noted the young man’s all-around talent and pegged him as a natural for the decathlon.

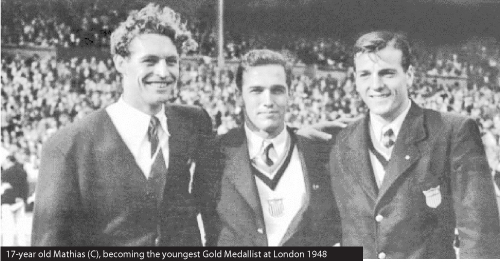

Two months after graduating high school and six weeks after participating in his first decathlon, Mathias travelled to the London 1948 Olympics Games. There, in the cold and rain and needing headlights from cars to be able to see, the 17-year Mathias won the gold medal and became the youngest men’s winner of an Olympic track and field event.

When Mathias returned home from London 1948, he was welcomed at a huge celebration in Tulare and presented with “Key to the City.”

Also, Mathias won the James E. Sullivan Award as the nation’s top amateur athlete, but as his scholastic record in high school did not match his athletic achievement, he had to spent a year at the Kiski School, a well-respected all-boys boarding school in Saltsburg, Pennsylvania. In 1949, Mathias won National Decathlon Championship at Tulare. He enrolled at Stanford University.

In 1950, at the National AAU championships, he won the National Decathlon Championship setting a world record with 8,042 points (later revised to 7,444 points, but still a world record) at Tulare, United States on June 30, 1950. He also won National Decathlon Championship in 1951. He continued playing football during his senior years at Stanford.

In 1952, he won his fourth National AAU championship, a feat never before accomplished, setting another world record with 7,829 points, far beyond his previous record of 7,444. This event was the final trial to select the U. S. Olympic team for the Helsinki 1952 Olympic Games in Finland.

On New Year’s Day of 1952, he played fullback for Stanford University in the Rose Bowl. The 6-foot-3, 204-pounder became the only athlete to ever play in the Rose Bowl and compete in the Olympics in the same year. Mathias was selected as the Associated Press ‘Male Athlete of the Year.’ He enrolled at Stanford University, where he played fullback for the Cardinal’s football team.

London 1948 Olympic Games

At the London 1948 Olympics, Mathias became the youngest member on any U. S. Olympic track and field team ever. He worked hard right up to the event. Unfortunately, training without allowing his body any recovery time caused elbow and knee injuries. These injuries, as well as the high calibre of the competition, made Mathias’s prospects for a medal look dim.

Prior to the competition, both the world record and Olympic record belonged to Glenn Morris of the United States for his achievement of 7900 points in Berlin, Germany on August 8, 1936.

On August 5, 1948, at 0700, Mathias breakfasted on steak and orange juice, then headed to London’s Wembley Stadium, where 70,000 spectators waited in a cold rain. Although he was not allowed to warm up before running his first event, the 100 meters, he managed to race the distance in 11.2 sec, a tie with his own personal record for the event.

On the long jump, he only made 21’ 8 ½”. This score was very low, putting him near the bottom of the field of 35 contenders. For the shot put, Mathias threw a distance of over 45 feet. However, because he unknowingly violated a technical rule in the way he stepped out of the shot-put circle after the throw he was forced to settle for a distance of 42’ 9 ¼”.

Between events the rains continued, and Mathias waited for his high jump event wrapped in a blanket. Missing his first two tries, the young man began to worry. If he missed a third time, he would be disqualified. On the third try, however, he made it, sailing over at 6’ 1 ¼”, his best height ever. His last event was the 400m run, which Mathias finished in 51.7 sec. After a long, cold, wet, and exhausting day, he found himself in third place in the Olympic decathlon.

On the second day, August 6, 1948, a stiff and sore Mathias awoke to find that it was still pouring. His first event of the day was the 110m hurdles, which he almost botched by losing his balance. Losing speed during his balance mishap, he poured on the speed to complete the run, finishing with a personal worst time ever of 15.7 sec.

He threw the discus 145 feet, but competitor Mondschein’s discus skidded across the wet grass, knocking Mathias’s marker from the place where his discus had originally landed. For half an hour Olympic officials wandered over the field arguing about where Mathias’s marker had been before positioning a new marker a foot and a half short of his actual throw. Despite this, the new distance of 144’ 4” was good enough to put Mathias in first place, with a 48-point lead.

At noon, Mathias was exhausted, cold, soaking wet, and hungry. However, officials refused to let him go to lunch, saying he might have to do his pole vault soon. They then divided the athletes into two groups, with Mathias in the second group. All the contenders had encountered difficulty with the pole vault because the pole and runway were slippery due to the rain. Mathias waited until the bar was over ten feet to take his turn.

At noon, Mathias was exhausted, cold, soaking wet, and hungry. However, officials refused to let him go to lunch, saying he might have to do his pole vault soon. They then divided the athletes into two groups, with Mathias in the second group. All the contenders had encountered difficulty with the pole vault because the pole and runway were slippery due to the rain. Mathias waited until the bar was over ten feet to take his turn.

By now, it was twilight, the only light coming from the Olympic torch, flickering through the rain and a string of 50-watt bulbs lighting the stands. Although the contest became almost dangerous in these conditions, Mathias continued vaulting on higher and higher bars until he cleared 11’ 5 ¾”. By now he was in second place, with only Ignace Heinrich of France ahead of him.

The next event was the javelin. It was night, and Mathias threw by the light of an official’s flashlight, even losing his javelin in the dark. By the end of the event, however, he was only 189 points behind Heinrich. If he could win the 1,500m, he would also win the gold. Exhausted, hungry, and suffering from pain in his foot and his stomach, a determined Mathias staggered across the finish line in 5:11, he was the Olympic champion. In just his third decathlon, the 17-year had registered 7,139 points.

Mathias sloshed to the stands and hugged his mother, as his father and two brothers cheered him. When asked how he planned on celebrating, the teenager said, “I’ll start shaving, I guess.” He then immediately went to sleep, and had to be awoken the next day so he could participate in the victory parade. He received a congratulatory telegram from President Harry S. Truman, was besieged by a crowd of 5,000 people at the airport on his return home, and was the star of a victory party in his hometown of Tulare.

The medallists: Gold - Bob Mathias of the United States with 7139 points; Silver - Ignace Heinrich of France with 6974 points; Bronze - Floyd Simmons of the United States with 6950 points.

Helsinki 1952 Olympic Games

The Men’s decathlon at the Helsinki 1952 Summer Olympic Games took place on July 25 and 26. There were 28 competitors from 16 nations.

The world record was held by Bob Mathias of the United States who scored 8,042 points (adjusted to 7,287 points) in 1950. The Olympic record was to the credit of Glenn Morris of the United States who had scored 7,254 points in Berlin, Germany on August 8, 1936.

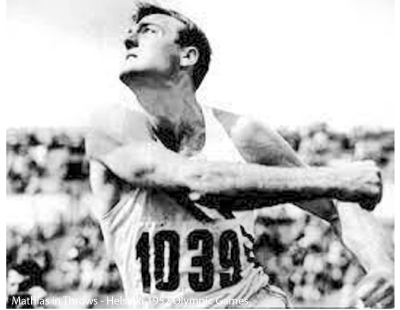

The weather in July was better in Helsinki, Finland, than it had been in London, and so was Mathias’ performance. He beat his career bests in the javelin (194-3) and the 1,500 meters (4:50.8) in romping to his second gold medal. He won the decathlon by the astounding margin of 912 points, becoming the first person to successfully defend an Olympic decathlon title.

His 7,887 points achievement (later adjusted to 7,592 as per 1998 tables) on July 26, 1952 was a new world record. In breaking his own world record, he triumphed over teammate Milt Campbell by a whopping 912 points, the largest margin in Olympic history.

At Helsinki in 1952, Mathias established himself as one of the world’s greatest all-around athletes. It was the second time the United States Olympic team earned all three medals in the event, the first one being in the 1936 Olympic Games.

The medallists: Gold - Bob Mathias of the United States with 7,887 points (new world and Olympic record); Silver – Milt Campbell of the United States with 6975 points; Bronze - Floyd Simmons of the United States with 6,788 points.

Post Retirement Career

After the 1952 Olympics, Mathias retired from competition undefeated in 11 decathlons. His career after graduating from Stanford in 1953 with a Bachelor of Arts in Education, was as versatile as the ability he showed competing in the decathlon.

He was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the U. S. Marine Corps, spent two and a half years, visited more than forty countries as America’s ‘Goodwill Ambassador’ from 1954 to 1956. He was promoted to the rank of Captain and was honourably discharged from the U. S. Marine Corps. He had earlier spent the summer of 1951 at the U. S. Marine Corps boot camp in San Diego, California.

He married Melba in 1954 and they starred in the movie “The Bob Mathias Story.” Also, they can be seen on the edition of April 29, 1954 of “You Bet Your Life.” He also starred in a number of mostly cameo-type roles in a variety of movies and TV shows throughout the 1950s. He continued work for the state department as a ‘Goodwill Ambassador’ to the world from 1956 to 1960.

In 1958, Mathias starred in the movie “China Doll,” the role of Captain Phil Gates. In the 1959–1960 television season, Mathias played Frank Dugan, with co-stars Keenan Wynn as Kodiak and Chet Allen as Slats. In 1960, he appeared playing an athletic Theseus in an Italian “peplum,” or sword-and-sandal film, “Minotaur, the Wild Beast of Crete” as Theseus” and the TV series “The Trouble-shooters” which focused 26 episodes on events at construction sites. In 1962, he appeared in the movie “It Happened in Athens” as Coach Graham. He also served as the President of the American Kids Sports Association.

In 1958, Mathias starred in the movie “China Doll,” the role of Captain Phil Gates. In the 1959–1960 television season, Mathias played Frank Dugan, with co-stars Keenan Wynn as Kodiak and Chet Allen as Slats. In 1960, he appeared playing an athletic Theseus in an Italian “peplum,” or sword-and-sandal film, “Minotaur, the Wild Beast of Crete” as Theseus” and the TV series “The Trouble-shooters” which focused 26 episodes on events at construction sites. In 1962, he appeared in the movie “It Happened in Athens” as Coach Graham. He also served as the President of the American Kids Sports Association.

In 1966, he was elected to the U. S. House of Representatives as a Republican. Between 1967 and 1975, Mathias served four two-year terms, representing the northern San Joaquin Valley of California. These were the same eight years in which Ronald Reagan served two terms as governor of California. Mathias defeated Harlan Hagen, the 14-year Democratic Party incumbent, by about 11% in the 1966 election. This was not too surprising because this area started to move away from its New Deal Democratic roots.

Mathias was re-elected three times without serious difficulty, but in 1974, his district was significantly redrawn in a mid-decade redistricting. His district was renumbered as the 17th District, and picked up a large chunk of Fresno while losing several rural areas. Mathias was narrowly defeated for re-election by John Hans Krebs, a member of the Fresno County Board of Supervisors.

He was inducted in the National Track and Field ‘Hall of Fame’ in 1974. From June to August 1975, Mathias served as the Deputy Director of the Selective Service. Mathias and Melba divorced in 1976 and he married Gwen Haven Alexander in 1977.

He later became the first Director of the United States Olympic Training Centre at Colorado Springs a post he held from 1977 to 1983. Tulare high school stadium was renamed in his honour in 1977. He was appointed Executive Director of the National Fitness Foundation in 1983. He was inducted the U. S. Olympic ‘Hall of Fame’ in 1983.

He returned to the Central Valley, in rural Fresno County in 1988. A tribute dinner honouring Mathias on the 50th anniversary of his first Olympic medal was held in Tulare on June 6, 1998. More than 300 people from throughout the state attended, including Olympic medal-winners Sammy Lee, Bill Toomey, Dave Johnson and Pat McCormick, and Sim Iness’ widow, Dolores.

Bob Mathias died in Fresno, California on September 2, 2006, aged 75. He was survived by wife Gwen, daughters Romel, Megan, Marissa, step daughter Alyse Alexander, son Reiner. He is interred at Tulare Cemetery in Tulare, California.

(The author is an Associate Professor, International Scholar, winner of Presidential Awards and multiple National Accolades for Academic pursuits. He possesses a PhD, MPhil and double MSc. His email is [email protected])