Francina “Fanny” Elsje Blankers-Koen was a Dutch track and field athlete, best known for winning four gold medals in athletics at the London 1948 Summer Olympic Games. She competed as a 30-year mother of two, earning her the nickname “the flying housewife,” and was the first post-World War II sporting superstar.

In 1999, she was voted “Female Athlete of the Century” by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF). Her Olympic victories are credited with helping to eliminate the belief that age and motherhood were barriers to success in women’s sport.

Apart from her four Olympic titles, she won five European titles and 58 Dutch championships, and set or tied 12 world records – the last, pentathlon, in 1951 aged 33. She retired from athletics in 1955, after which she became captain of the Dutch female track and field team.

Birth and Early Life

Fanny Koen was born on April 26, 1918 in Lage Vuursche to Arnoldus and Helena Koen. Her father was a government official who competed in the shot put and discus. Standing 1.75m, she was a natural athlete. She had five brothers and as a teenager enjoyed tennis, swimming, gymnastics, ice skating, fencing and running.

It soon became clear that she was talented, but she could not decide which sport to pick. A swimming coach advised her to concentrate on running stating that she would have a better chance to qualify for the Olympics in a track event.

Her first appearance was in 1935, aged 17. In her third race, she set a national record in the 800m. Fanny Koen soon made the Dutch team as a sprinter. At that time, 800m was generally considered too physically demanding for female athletes, and had been removed from the Olympic program after 1928.

In 1936, her coach and future husband, Jan Blankers, a former Olympic triple-jumper who had participated in the 1928 Olympics, encouraged her to enter the trials for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. At 18, she was selected to compete in the high jump and the 4x100m relay.

At the Berlin Olympics, the high jump and the 4x100m relay competitions were held on the same day. In the high jump, she was fifth while the Dutch relay team as well came fifth. She obtained the autograph of American athlete Jesse Owens and it became her most treasured possession.

In 1938, she ran her first world record of 11.0 secs in the 100 yards, whilst winning her first international medals. At the European Championships in Vienna, she won the bronze in both the 100m and 200m. Many expected her to do well at the upcoming Olympicsin Helsinki in July 1940.

However, the outbreak of World War II put a stop to the preparations. The Olympics were formally cancelled on May 2, 1940, a week before the Netherlands was invaded.

World War II

Just prior to the invasion, Koen had become engaged, and on August 29, 1940, she married Jan Blankers, thereupon changing her name to Blankers-Koen. Blankers was then a sports journalist and the coach of the Dutch women’s athletics team, even though he originally thought women should not compete in sports, his attitude toward female athletes changed.

When Blankers-Koen gave birth to her first child, Jan Junior, in 1942, Dutch media automatically assumed her career would be over. Top female athletes who were married were rare at the time, and it was considered inconceivable that a mother would be an athlete. Blankers-Koen was back on the track after a few weeks of their son’s birth.

During the war, domestic competition in sports continued in German-occupied Holland, and Blankers-Koen set six new world records between 1942 and 1944. The first came in 1942, when she improved the world mark in the 80m hurdles. The following year, she did even better by improving the high jump record by an unequalled 5 cm from 1.66m to 1.71m in Amsterdam on May 30, 1943.

During the war, domestic competition in sports continued in German-occupied Holland, and Blankers-Koen set six new world records between 1942 and 1944. The first came in 1942, when she improved the world mark in the 80m hurdles. The following year, she did even better by improving the high jump record by an unequalled 5 cm from 1.66m to 1.71m in Amsterdam on May 30, 1943.

Then, she tied the 100m world record, but this was never recognized officially, as she competed against men when setting the record. She closed out the season with a new world record in the long jump, 6.25m on September 19, 1943, which stood until 1954.

Circumstances were not easy, and it became harder to get enough food, especially for an athlete in training. Despite this, she managed to break the 100 yd world record in May 1944. At the same competition, she ran with the relay team that broke the 4x110 yd world record.

Months later, she helped break the 4x200m record, which was held by Germany. The winter of 1944–45, was severe. She gave birth to a daughter, Fanneke, in 1945 and in contrast to her previous post-birth activities she took seven months off from sport.

Competitions after the World War II

The first major international event after the war was the 1946 European Championships in Oslo, Norway. In the 100m semi-finals, held during the high jump final, she fell and failed to qualify. Competing with bruises from the fall, she ended the high jump competition fourth.

The second day she won the 80m hurdles and led the Dutch relay team to victory in the 4x100m. In 1947, as the leading female athlete in the Netherlands, she won national titles in six women’s events.

After her experience in Oslo, she decided not to take part in all events, but limit herself to four: she dropped the high jump and long jump and concentrated on the 100, the 200, the 80m hurdles, and the 4x100 relay.

Although she displayed her form two months before the Games by beating her own 80m hurdles world record – one of the six world records that she held at that time – some journalists suggested 30 years was too old for a woman to be an athlete.

Many in the Netherlands were concerned for the welfare of the family, saying that she should stay at home to look after her children, not compete in athletics events.

London 1948 Summer Olympics

Blankers-Koen went to London as a 30-year-old mother of two and her expectations were not much higher than to relive the excitement of her previous Olympic experience in Berlin in 1936, when she was a bright-eyed teenager.“I hoped to get into a final, that would have been a highlight for me,” she told a Dutch TV documentary decades later.

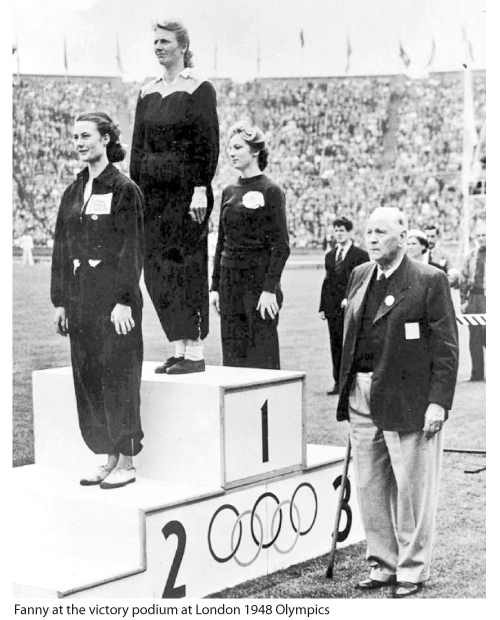

Yet in a matter of days, Blankers-Koen romped to the 100m gold, then the 80m hurdles, the 200m by a runaway margin and finally anchored the Dutch to gold in the 4x100m relay, taking the baton in fourth place and powering her long legs through the field.

In the process she offered legitimacy to women’s sport, debunked myths about motherhood and competition, and helped lift her nation out of post-war gloom.She might have won more at the Games in London but was restricted to just three individual events plus a relay, even though she had held the world record, at one time or another, in six different disciplines.

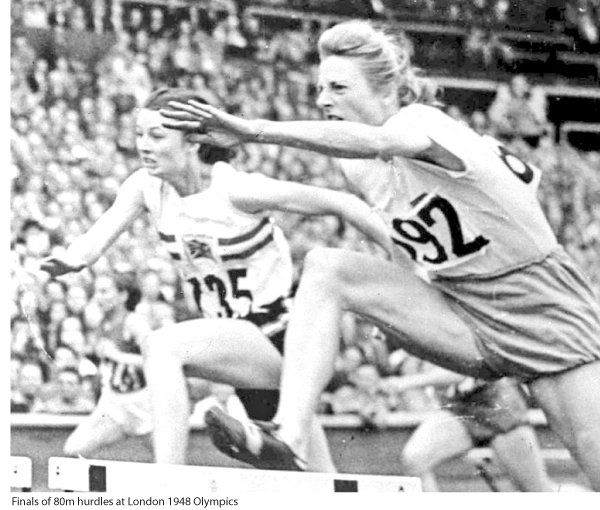

Fanny Blankers-Koen became the first Dutch athlete to win an Olympic title in athletics when she won 100m. Yet, she was more concerned with her next event, the 80 m hurdles. Her chief opponent was Maureen Gardner, also coached by Blankers-Koen’s husband and who had equalled Blankers-Koen’s world record prior to the Games. Both athletes made the final, in which Blankers-Koen got off to a bad start.

She picked up the pace quickly, but was unable to shake off Gardner, who kept close until the finish line, and the two finished almost simultaneously. When the British national anthem was played, the crowd in Wembley Stadium cheered, and she briefly thought she had been beaten. However, the anthem was played in honour of the British royal family, which entered the stadium at that time. Examination of the finish photo clearly showed that not Gardner, but Blankers-Koen had won.

In spite of her successes, Blankers-Koen nearly failed to start in the semi-finals of the 200m. Shortly before the semi-final, she broke down because of homesickness. After a long talk with her husband, she decided to run and qualified for the final. The final, was again held in the pouring rain, but she won the inaugural Olympic 200m for women in 24.4, seven-tenths of a second ahead of runner-up Audrey Williamson – still the largest margin of victory in an Olympic 200 m final.

The 4x100m final was held on the final day of the track and field competitions. The Dutch team, consisting of Xenia Stad-de Jong, NettyWitziers-Timmer, Gerda van der Kade-Koudijs and Blankers-Koen, qualified for the final, but just before the final, Blankers-Koen was missing. She had gone out to shop for a raincoat, and arrived just in time for the race. As the last runner, she took over the baton in third place, some five meters behind the Australian and Canadian runners. Yet, she caught up with the leaders, crossing the line a tenth of a second before the Australian team.

Fanny Blankers-Koen won four of the nine women’s events at the 1948 Olympics, competing in eleven heats and finals in eight days. She was the first woman to win four Olympic gold medals, and achieved the feat in a single Olympics. Dubbed “the flying housewife,” “the flying Dutchmam,” and “amazing Fanny” by the international press, she was welcomed back home in Amsterdam by an immense crowd. After a ride through the city, pulled by four white horses, she received a lot of praise and gifts. From the city of Amsterdam, she received a new bicycle: “to go through life at a slower pace” and “so she need not run so much.” Queen Juliana made her a knight of the Order of Orange Nassau.

Fanny Blankers-Koen won four of the nine women’s events at the 1948 Olympics, competing in eleven heats and finals in eight days. She was the first woman to win four Olympic gold medals, and achieved the feat in a single Olympics. Dubbed “the flying housewife,” “the flying Dutchmam,” and “amazing Fanny” by the international press, she was welcomed back home in Amsterdam by an immense crowd. After a ride through the city, pulled by four white horses, she received a lot of praise and gifts. From the city of Amsterdam, she received a new bicycle: “to go through life at a slower pace” and “so she need not run so much.” Queen Juliana made her a knight of the Order of Orange Nassau.

She was overwhelmed by the reception she received on her return to the Netherlands. “It was very strange because before there wasn’t interest in track and field. And then there was so many people and you feel like a queen. My world changed at that time, after the Games,” she recalled.

She told biographers she never got rid of her anxiety despite her superstar status. “I was always nervous and unsure but in one way it was a positive, because I was never sure of winning. The angst in my shoes was probably my advantage.”

After London 1948 Olympics

Now known all over the world, Blankers-Koen received many offers for endorsements, advertisements, publicity stunts, and the like. Because of the strict amateurism rules in force at the time, she had to turn most offers down. However, in 1949, she travelled abroad to promote women’s athletics, flying to Australia and the United States.

Blankers-Koen had been chosen the 1948 Helms Athletic Foundation World Trophy Winner for Europe. The same year, she almost repeated her Olympic performance at the European Championships in Brussels. She won the titles in the 100m, 200m and 80m hurdles, but narrowly missed out on a fourth win in the relay.

At age 34, she took part in her third Olympics, which were held in Helsinki. Although she was in good physical condition, she was severely hampered by a skin boil. She qualified for the 100m semi-finals, but forfeited a start to save herself for the hurdles race. She reached the final in that event, but after knocking over the second hurdle, she abandoned the race. It was her last major competition. On August 7, 1955, she was victorious for the last time, winning the national title in the shot put, her 58th Dutch title.

Later Life and Death

After her athletic career, Blankers-Koen served as the team leader of the Dutch athletics team, from the 1958 European Championships to the 1968 Summer Olympics.

In 1977, Blankers-Koen’s husband Jan died. Some years after his death, she moved back to her old hometown of Hoofddorp. In 1981, the Fanny Blankers-Koen Games, an international athletics event, were established. They are still held annually in Hengelo.

At a gala in Monaco, organized by the IAAF, she was declared the “Female Athlete of the Century.” She was very surprised to have won. She was a sprightly 81-year-old in 1999 and she delighted a news conference with her astonished reaction when congratulated on her achievement. “You mean it is me who has won. I had no idea!”

In the years prior to her death, Blankers-Koen suffered from Alzheimer’s disease and lived in a psychiatric nursing home. She passed away on January 25, 2004, aged 85.

A year before her death, the first biography of Blankers-Koen was published, “A Queen with Men’s Legs” by journalist Kees Kooman. Through many interviews with relatives, friends and contemporary athletes, it paints a previously unknown picture of her.

During her successful years, Dutch and international media portrayed her as the perfect mother, who was modest about her own achievements. Kooman’s book portrays Blankers-Koen in a different light, as a woman who found it difficult to show affection and who was driven by a desire to win. Blankers-Koen had previously written an autobiography in 1949 with help from her husband.

Her personal record on the 100m of 11.5 remained the Amsterdam club record of Phanos for 62 years. It was finally broken in May 2010 by Jamile Samuel.

Awards and Tributes

Dutch Athlete of the Year - 1937, 1940, 1943; Associated Press Female Athlete of the Year - 1948; Knight of the Order of Orange-Nassau - 1949; Medal of the NOC*NSP - 1949; Royal Dutch Athletics Federation honorary member - 1949; IAAF Female Athlete of the 20th Century - 1999; IAAF Hall of Fame - 2012.

She was among the women included in the 1001 Vrouwenuit de Nederlandsegeschiedenis, a dictionary of biography covering 1001 important Dutch women. In a 2004 national poll, Blankers-Koen ranked 29th for De Grootste Nederlander (The Greatest Netherlander); she was the third highest sportsperson and the seventh highest woman in the poll.

Two public statues of her have been erected in the Netherlands: the first by Han Rehm in Rotterdam in 1954 and the second by Antoinette Ruiter, in Hengeloin 2007. Also a plaque was placed in the sports park at Olympiaplein in Amsterdam in 2007 declaring “Hiertrainde Fanny Blankers-Koen.”

Several locations have been named in her honour, including Blankers-Koen Park in Newington, New South Wales, the location of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Village, a fire station in Amsterdam, a park in Almere, and a sports hall in Hoofddorp where she lived.She was honored with a Google Doodle on April 26, 2018, on what would have been her 100th birthday.

(The author is the winner of Presidential Awards for Sports and recipient of multiple National Accolades for Academic pursuits. He possesses a PhD, MPhil and double MSc. He can be reached at [email protected])