Belgian surrealist artist Rene Magritte (1898-1967) writes that research done by modern painters is the result of a grave mistake. They wish to determine the style of a painting a priori. This style is the inevitable result of a well-made object, the union of the creative idea and its realisation. As for producing this work, a genius without a method of expression is sterile and a painter, therefore, must have a thorough mastery of the material resources at his disposal and use them strictly according to their laws.

Belgian surrealist artist Rene Magritte (1898-1967) writes that research done by modern painters is the result of a grave mistake. They wish to determine the style of a painting a priori. This style is the inevitable result of a well-made object, the union of the creative idea and its realisation. As for producing this work, a genius without a method of expression is sterile and a painter, therefore, must have a thorough mastery of the material resources at his disposal and use them strictly according to their laws.

The master of his craft and not the slave. The real work is in the layout, the choice of line, shape and colour which will automatically trigger aesthetic sensations, the pictures raison d’etre.

Mastered resources

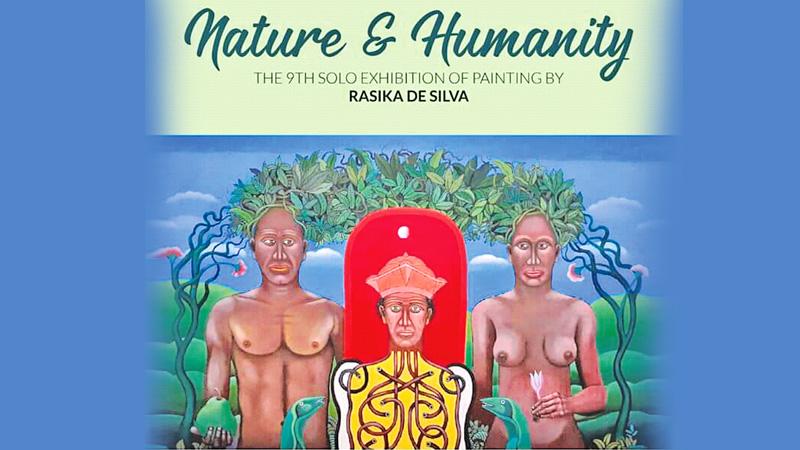

Rasika de Silva’s paintings exhibit the evolution of a painter that has over time mastered the resources at his disposal. His paintings and the subjects within them have evolved in clarity and his style and technique have grown to perfectly suit his choice of subject. It is clear in his paintings that Rasika has not fallen prey to the mistake of a priori determination of the style of a painting.

Though the existence of gravity is proved by the laws that influence all bodies, what may trigger aesthetic emotion seems not to exist except in man’s imagination and is created by him out of nothing; so, to discover what it is, you have to be a different kind of seeker than a gold miner, you have to create what you are searching for, and artists have a natural affinity for this. Rasika has in the past demonstrated this affinity within himself, creating in his works on “Nature and Humanity”, what has been described as a deeply personal vision.

Though the existence of gravity is proved by the laws that influence all bodies, what may trigger aesthetic emotion seems not to exist except in man’s imagination and is created by him out of nothing; so, to discover what it is, you have to be a different kind of seeker than a gold miner, you have to create what you are searching for, and artists have a natural affinity for this. Rasika has in the past demonstrated this affinity within himself, creating in his works on “Nature and Humanity”, what has been described as a deeply personal vision.

Painting has continued to “evolve” since Courbet’s realism.

Evolution

Impressionism, Expressionism, Fauvism and Cubism have been followed by Mondrian’s abstract art. In reality, this evolution was the succession of different manners of seeing the art of painting regarding its strictly formal aspect. In other words, the only minimal freedom allowed was in how to paint, “what was painted” had little importance.

Reality itself was not called into question, and for this reality to be questioned we needed the “poet’s freedom”. Consequently, if artists were going to go on painting, the importance attached to how to paint had to be shifted to the importance of a presence that is not incidental: the importance of the world and thought.

Rasika has always demonstrated this “poet’s freedom”, and to his credit has evolved in his vision, moving from a personal vision to a broader, global one, he seems now to be contending with the relationships between man, the weapons he builds and nature, amongst other things.

In a more local sense yet in keeping with the expansive vision he has created, he contends with the island mentality in Sri Lanka, taking on such issues as conflicts within social strata. His technique or style further reflects this by not being easily definable, drawing from numerous manners of painting, stretching from surrealist to the abstract as it works for the discovery of Rasika’s subject.

Realities

Of Magritte, journalists wrote that “from the most accurate figurations he arouses the strange.” If Magritte had only given us the “strange”, some say the “fantastic, his paintings would have joined the lineage of Hieronymus Bosch and James Ensor, who attempted to entertain, perhaps to enchant, without giving us knowledge of the world. “Strange” and the “fantastic” often merely allow evasion or an “escape from reality”. Whilst Magritte’s surrealist work, were instead born of questioning reality, Rasika, in his place has borne these new pieces out of a confrontation with the truth of the realities of our modern world.

His painting ‘Living with the Death’ depicts a figure with an adornment of medusa-esque vines tightly grasping close a fish with stabilising fins, juxtaposes directly, nature and technology, commenting on the exploitation of nature in the creation of weapons.

The clarity of the subject in the foreground from the conflicting colors of green and the vibrant almost artificial orange in the background, the calm in the eyes of the figure coupled with the chimp-like bared teeth, the staring dead fish-eye and the writhing curls of vines create a sense of foreboding in the viewer. A raw yet refined picture of the truth Rasika has seen in his wrestling with the world.

Man’s view of himself

In 1917, neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) listed the three mortal wounds inflicted by man’s view of himself. Copernicus had shown that he was a mere dot in the vast universe; Darwin, that he was an ape, and Freud himself exposed man as a slave to the unconscious mind.

In his words: “Humanity has in the course of time had to endure from the hands of science two great outrages upon its naive self-love.

The first was when it realised that our earth was not the center of the universe, but only a speck in a world-system of a magnitude hardly conceivable; The second was when biological research robbed man of his peculiar privilege of having been specially created, and relegated him to a descent from the animal world, implying an ineradicable animal nature in him.

Suffering the third and most bitter blow from present-day psychological research which is endeavoring to prove to the ‘ego’ of each one of us that he is not even master in his house, but that he must remain content with the veriest scraps of information about what is going on unconsciously in his mind.” Rasika’s painting ‘Disconnected Man’ is reminiscent of this idea.

The vacant eyes and the docile expression on the subject in the painting almost lull the observer into a state of complacent viewing, were it not for the mass of tangled empty vessels, curling around the obvious emptiness which draws the eye.

The contrast of what is and what should be is used to hold the attention of the observer and create the image of man divorced irreparably from himself, in the starkest fashion.

Rebellion

The French Absurdist Albert Camus (1913-1960) wrote that: “Rebellion in man is the refusal to be treated as an object and to be reduced to simple historical terms. It is the affirmation of a nature common to all men which eludes the world of power.” Rasika’s painting ‘Natives’ evokes this spirit of rebellion. A dark island of green claustrophobically encloses the figures in the foreground.

Two figures dressed in traditional Sri Lankan attire flank a man in a western suit and a traditional hat, whose mismatched attire and defensive posture create an uncomfortable dissonance in the mind of the observer. The hats seem like fetters to rotting systems built by dead men.

All the while two dark owls stare unblinkingly, unsettlingly examining the observer. Camus wrote on rebellion against abusive power and outdated systems and Rasika seems to invoke the same metaphysical spirit of revolt, perhaps at the suffering caused by the remnants of class and caste, hierarchies of power and aged systems which protect themselves.

Representation

Painters often hear the question “what does it represent?” and one can get lost in a maze of literary interpretations which have nothing to say. This question asked of one of Rasika’s paintings merely means “How should I understand this?” because it is obvious if we look, for example, at natives that we are seeing three men who do not leave us indifferent.

If it were known that understanding the image was a case of seeing it and not sterile intellectualising through course symbols that the artist and observer can do almost nothing with, this question would not be asked.

Therefore, there is only one way to answer the question “what does it represent?’ at the risk of not satisfying; people must know that a painting by Rasika means exactly what faithful description can be made of it. At most, we can define Rasika’s thought, and speech can describe in words that the eyes are looking at, even if silence would be better suited.