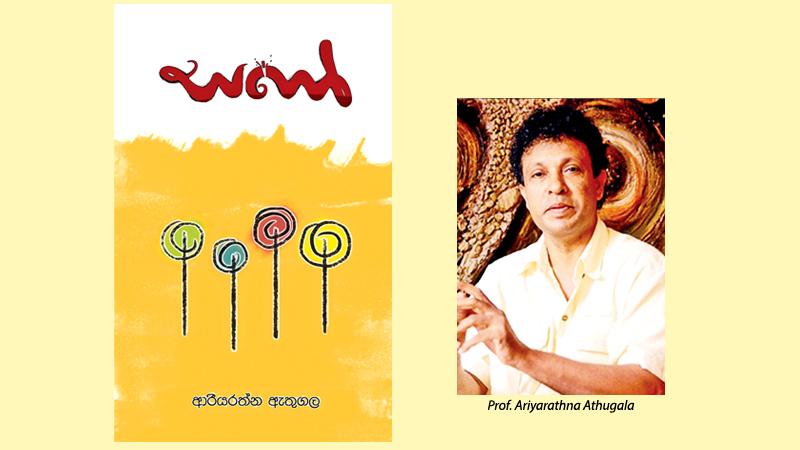

Saho (the Comrade) is a novel that deserves better attention from sophisticated readers. It is written by Ariyarathna Athugala, a Sri Lankan academic who has shown his talents and skills previously as a prolific writer and a playwright.

A group of college students living in an unspecified college campus in Sri Lanka is central to the novel.

The dramatis personae are Tharu, Sandu, Hiru, and Ratu. Sandu has freshly graduated from college and secured a dubious probationary college teaching position, which would not be likely to last over an academic year. Nearing graduation, her friends face an equally uncertain future.

The dramatis personae are Tharu, Sandu, Hiru, and Ratu. Sandu has freshly graduated from college and secured a dubious probationary college teaching position, which would not be likely to last over an academic year. Nearing graduation, her friends face an equally uncertain future.

Their unsettled prospects notwithstanding, the main characters in the novel are inclined to become entangled in the themes common to their age groups in a college campus environment, such as romance, ambition and the generally lukewarm reception to authority, control and convention.

Hence Saho is a work fitting well with the genre of novels known in the West as college novels. Sometimes known as academic or campus novels, this genre often appeals to its niche audience, consisting of high schoolers, college students and the likes. Aligning with the popular trope that college is the happiest four years of one’s life, at times, some college novels (and the movies based on such novels) have been successful in grabbing readers’ attention beyond their traditional constituency.

Prefab cultural landscape and atemporal order

Prefab cultural landscape and atemporal order

emThe story unravels in a prefab cultural landscape. The author carefully confines his chosen characters and their activities mostly into several places in the college campus, such as the playground, the cafeteria, the classrooms, the library, undergraduate dormitories and private boarding houses.

This made-beforehand landscape and those who inhabit in it exist without relation to time, as if they live in an eternal present. Atemporal order is accentuated due to another reason.

The names of most characters in the novel bear cosmic connotations. As a result, the reader feels galactic. More to the point, the main characters express this-worldly feelings, thoughts and actions while alluding to Other-Worldly or extraterrestrial vastness simultaneously.

For instance, they see some lecturers’ conduct in this college campus as akin to that of extraterrestrial beings (p. 26).

Moreover, they jokingly point out that a thinly made string hopper is worthy for nothing but to use as the protective viewing of a solar eclipse! (p. 79). Likewise, Rathu, a main character in the novel insinuates the following: Hiru’s sunrays have boosted Saho’s morality, Sandu’s moonlight has awakened his desire and Tharu’s rock-throwing (after appearing on the scene like a comet rose from the distant sky) has brought a tragic end to Saho’s life (p. 65).

Nostalgic camaraderie

Although the main characters share the commonality of being relatable to each other as young adults facing similar predicaments in a college campus environment, they also impart profound dissimilarities.

For instance, Sandu can spew lines from classical English literature in her class sessions while others in the group reacting cluelessly as if the linguistic barrier is something insurmountable. Similarly, Hiru proves in the end that she can hang out with her friends while concealing her complicit life. By the same token, Rathu can mingle with his friends while insinuating their responsibility for Saho’s death simultaneously. The strongest commonality they all share is nostalgic camaraderie.

Let me describe succinctly what nostalgia does. Nostalgia essentially crushes the surface of an atemporal order and a prefab cultural landscape. It does so by resurrecting time and place. It sets up a frame of meaning within which positing a “once was” in relation to “now” is possible.

Nostalgia is a crucial narrative function of language that orders incidents temporally while dramatising them in the mode of “things that happened,” that “could happen,” and that “are happening now.” In this sense, to narrate a story is to place oneself in an event and a setting, and to relate something to someone. In other words, nostalgia makes it possible to create a relational interpretive space in which meanings have straight social antecedents.

Novel to film adaptation

It is to this interpretive space the author brings in the competing memories of camaraderie, a core concept of mutual trust, friendship and unity.

The strength of Athugala’s novel rests on his adroit depiction of Saho, the deceased protagonist of the narrative through competing nostalgic memories. At the novelist’s hand, Saho has become an interpretive space where competing memories of camaraderie are presented, negotiated, contested and fiercely fought out.

His immanent and pervasive presence is made manifest in such a way that the reader begins to feel Saho’s living presence. Let me end this brief note on Professor Athugala’s novel by adding a word on its transition to a film.

“I first wrote the screenplay,” says the author in the preface of the book, inferring that it was the film project that he had in mind at first and on his way of getting that job accomplished, the novel came into being later. If one sets aside the familiar query which came early, the chicken or the egg, one cannot help but remember that many college novels in the West have become college films later.

For example, German writer Heinrich Mann’s 1905 novel Professor Unrat or ‘Professor Filth’ was one of the earliest predecessors to the genre of college novel.

The movie, adapted from the book by the German director Josef von Sternberg, was Der Blaue Engel or ‘The Blue Angel’ (1930). The film was the first feature-length German full talkie. It presented the tragic transformation of a respectable professor (played by Emil Jennings) to a cabaret clown and his descent into madness.

While bringing Marlene Dietrich (who played the role of Lola-Lola, the cabaret dancer and singer) international fame, the film also introduced another distinguishable trait in the genre of college film and its sister categories, the film of teenage romance and melodrama and the coming-of-age film.

That hallmark was the film’s musical score and the songs which could sensationalise the audience. As mentioned by film historians, when Marlene Dietrich was singing “Falling in Love Again” in the movie, Western filmgoers at the time have embraced not only the playful, flirtatious and self-consciously seductive character of cabaret girl and the nutty professor, but also the musical score that immensely helped Dietrich to deliver it.

Although the college film genre was introduced to Sri Lankan cinema by the veteran film director Sugathapala Senerath Yapa with his Hanthane Kathawa or ‘Story at Hanthana’ in 1968, this category never became a well-established movie genre. Subsequently, Yapa’s film spawned a trove of trivial imitations and cheap parodies in many Sri Lankan films, however.

Only a few films that can be genuinely considered college films arose subsequently. Wasantha Obeyesekere’s 2002 film Salelu Warama or ‘The Web of Love’ and Asoka Handagama’s Ege Esa Aga or ‘Let Her Cry’ (2016) were two of such distinctive college films.

Several teenage romantic melodrama films also followed. One of the earliest movies in this category was Ranjith Lal’s Nim Walalla or ‘Horizontal Line’ (1970). Lester James Peris’s Golu Hadawatha or ‘Silent Heart’ (which was based upon Karunasena Jayalath’s novel bearing the same title) was screened in 1972.

The plot of Sumithra Peris’s film Gehenu Lamai or ‘Girls’ was adapted from Karunasena Jayalath’s novel. It was released for Sri Lankan film audience in 1978. In addition, Sunesh Dissanayake Bandara’s 2004 film Adaraneeya Wassanaya or ‘Romantic Rainy Season’ was elicited from Upul Shantha Sannasgala’s novel ‘Wassana Sihinaya’. Just as their Western counterparts, the musical score and some of the songs in these movies could sensationalise Sri Lankan niche audiences.

Allegory and cinematic metaphor

Let me give an example of how great filmmakers combine realism with a parable of life. Let us focus on the Japanese New Wave film Woman in the Dunes (1964). This was the film characterised by the American film critic Roger Ebert as “a modern version of the myth of Sisyphus, the man condemned by the gods to spend eternity rolling a boulder to the top of a hill, only to see it roll back down” (Chicago Sun-Times, February 2, 1998). In this black-and-white film adapted from the novel penned by Kobo Abe in 1962, the director (Hiroshi Teshigahara), the writer of the screenplay (Kobo Abe), the cinematographer (Hiroshi Segawa) and the composer of music (Toru Takemitsu) fruitfully collaborate to construct one of the most powerful cinematic metaphors that I have ever seen.

“In line with Plato’s Allegory of the Cave that it invokes in the beginning (in Chapter 2), Athugala’s novel unfolds to become a college novel with an allegoric flavour. Even though the action of the novel takes place in a realistic space, the characters inhabiting that space seem to act almost like the dramatis personae in an allegory. When one reads an allegory in the form of a novel, the narrative acts as a moral lesson or message.

In an allegoric work, concrete things such as characters, setting and objects are likely to represent deeper meanings. When adapting a novel with an allegoric tinge to a film, it generates a fertile ground for a cinematic metaphor to germinate and thrive. Saho is a promising college novel that warrants heeding of the refined reader.