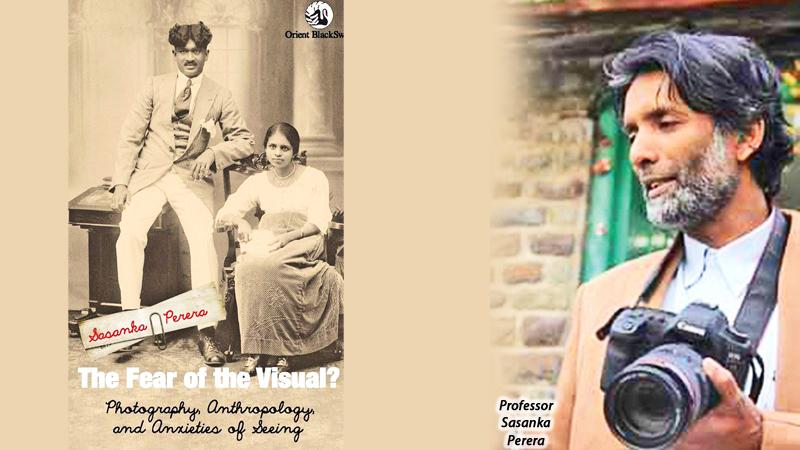

Sasanka Perera’s new book, The Fear of the Visual? Photography, Anthropology, and Anxieties of Seeing (2020) covers various topics that have been systematically explored. As the title suggests, why has there been a reluctance on the part of sociologists and social anthropologists to address visuality in their work?

Specifically in the context of this book, why have these disciplines pushed photography into the sub-disciplinary practice of visual anthropology or visual studies? The framework that the author lays out in the book is broadly in the areas of photography, anthropology and the complicated relationship between the two.

Specifically in the context of this book, why have these disciplines pushed photography into the sub-disciplinary practice of visual anthropology or visual studies? The framework that the author lays out in the book is broadly in the areas of photography, anthropology and the complicated relationship between the two.

He culls out his narrative from the sphere of personal reflections, historical insights and anthropological-sociological pluralism. The book has eight chapters that deals with diverse aspects, but are organically linked.

Academic rigour

While unravelling the uncomfortable relationship photography has with the disciplines of sociology and social anthropology, Perera’s main entry point into the discussion is his personal journey with photography.

But the discussion, despite its personal nuances, has the benefit of academic rigour. He writes, “what I have written in this book is personal and academic at the same time. It is personal because photography has been an integral part of my life for a long time and that involvement began long before my academic interest in the subject.

It is academic because what I discuss goes much beyond the personal and the private to deal with issues of representation, politics, power, ethics and the aesthetics of photography” (Perera 2020: 1).

But because Perera is a master storyteller, he does not load his readers with jargon and names of too many scholars. Since it is a work based on the significance of visuals, it is also a rare example of legitimising personal experiences in sociological writings.

Burden of representation

He provides an apt justification for his narrative style which is closely linked to his own subjective self “...if the ‘personal is political’, as once famously argued by American feminist Carol Hanisch in 1970, then the personal, in the sense in which I have used my recollections in this collection of essays, is quite clearly sociological” (Perera 2020: 28).

One of the reasons why photographs are not often taken seriously in ethnographic writings is because of the suspicions that concerns the ‘truth’ claims of representation.

One of the reasons why photographs are not often taken seriously in ethnographic writings is because of the suspicions that concerns the ‘truth’ claims of representation.

For Perera, as in the case of written text, there are multiple realities and truths in any photograph, “… when reading photographs, one has to take into account the multiple subjectivity that have come into photographs on the basis of the subjectivity of time and place, of the photographer and of the people in the photograph.

Thus, in any given context, there can be more than one reality or one truth in any photograph” (Perera 2020: 20).

Photographs are more often subjected to the undue burden of representation. While referring Berger (2013) and Susan Sontag (1977),Perera argues, “why should any text be so autonomous as to have no inter-textual relations of any kind? Why do we impose on photography such narrative preconditions when we do not impose these as rigidly on other kinds of texts, including the written or the spoken word? It seems to me that it is precisely because of its visuality that often unreasonable demands of narrativity are forced upon photography” (Perera 2020: 21).

As his story unfolds, the author throws light on the colonial elite legacy of taking and using photographs. He also focuses on the transition of this practice to the realm of the masses.

Beyond history of photography and anthropology, Perera also deals with contemporary practices, such as selfies, wedding photography and pre-wedding photo-shoots with wit and fascinating insights.

The two most captivating chapters for me are Chapter 4 – ‘Selfies’ and the Meanings of the Self and Chapter 5 – Framing and Performing Intimacy: An Incomplete Social History of Wedding Photographs. The author does manage to break some popular taken-for-granted notions regarding photographic practices. For instance, selfies which are mostly perceived as a recent innovation traces its legacy from self-portraits.

Even renowned artistes have produced their self-portraits; Van Gough, for one example. As he indicates, “As an idea, what we refer to as ‘selfies’ in the digital age of today is nothing new.

What is new is what appears to be people’s obsession with endlessly replicating images of themselves, mostly due to the availability of affordable and readily accessible technology and the availability of good cameras in mobile phones, which can be easily used by the people, including children” (Perera 2020: 119).

In the fifth chapter on wedding photography, besides the innovations in this genre over time, he sheds an important light on the ubiquitous smile and connects it with dental hygiene, technology, etiquette and historical events, such as the end of World War II in addition to the influence of American culture.

Issues and solution

The terrain of ubiquity of camera technology and ethics is a trickiest issue (Chapter 7). Perera raises a host of issues and manages to offer a workable solution when he notes, “… much is left to the common sense of researchers and to their personal dynamics within which they might interpret the visual ethics that confront them, based upon the general ethical principles of social research and personal decency, which hopefully will be an integral part of their professional training and habitus” (Perera 2020: 229).

One common feature that runs throughout this unique book is an unapologetic and provocative style of writing in which the ‘self’ has not been exiled into the pseudo-intellectual world of objectivity. As he notes, “in this effort, I have situated my undisguised subjective self as well as my anxiety-ridden academic self” (Perera 2020: 245) squarely in the centre of this book.

As he states, “that itself is perhaps too unorthodox an approach when seen from the perspective of the clinical and what I consider the boring and often-colourless domains of formal sociology and social anthropology in South Asia.

I am sure that for many of my colleagues, what I have said will not be adequately ‘sociological’” (Perera 2020: 245). Perera does not shy away from making students and scholars in the discipline of Sociology and Social Anthropology uncomfortable.

This discomfort might in turn open new vistas in research. In any case the book leaves us with much scope to agree, disagree, reflect and explore in various ways what taking a photograph seriously might mean in ethnographic endeavours.