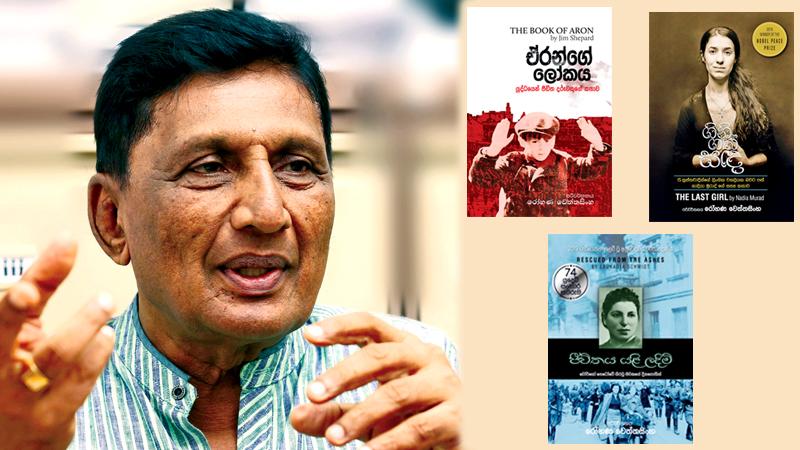

Veteran journalist Rohana Wettasinghe’s new book Jeevithaya Yali Ladimi which is a Sinhala translation of Rescued from the Ashes by Leokadia Schmidt, was launched recently as a Sarasavi Publication. This is Rohana’s third translation work and fifth book. The Sunday Observer spoke to Rohana Wettasinghe to discuss his book and his journalistic experience.

Excerpts

Q. Your translation is based on a holocaust book Rescued from the Ashes. Could you describe the original book?

A: Rescued from the Ashes was first published in 2018. The author, Leokadia Schmidt, is a Polish woman and a survivor of the Warsaw ghetto in Poland.

She started to record the horrific experience she underwent at the Warsaw ghetto and war time Poland in Polish in 1949. This is a document on Nazi crimes during the Second Word War.

Rescued from the Ashes was translated from the Leokadia’s Polish manuscript by Prof Oscar E. Swan who is an American and expert in Slavic languages.

Though the Polish manuscript had been completed in 1972 by Leokadia Schmidt, the English translation wasn’t published until 2018 because of the translator’s busy academic life. However, when the book was launched in 2018, Leokadia was no more.

Q.: There are hundreds of thousands of Holocaust books in the world. What’s the uniqueness of this book?

A: Every Holocaust book has its own uniqueness that shocks the reader. Leokadia Schmidt, her husband and her five-month-old son had to live in the Warsaw ghetto until July 22, 1942 when the Nazis started demolishing the ghettos in Warsaw.

By chance, they were able to move to an Aryan people residential area in Warsaw where pro-Hitler people lived. Though they narrowly escaped from the concentration camps or death at gas chambers in Auscwitz, they had to endure many hardships as they were Jews. Leokadia had to do various jobs that are not suitable for a woman, with her five-month-old son. This is the uniqueness of the book. Leokadia never abandoned her baby although she was forced to work without children.

Finally, she rescued not only herself, but also her baby along with her husband. Rescued from the Ashes is an example of women’s fighting spirit.

Wladyslaw Bartoszewski, Auschwitz survivor, resistance fighter and historian of the Nazi occupation of Poland said, “Observational skill and judgmental honesty are among the fundamental values of Leokadia Schmidt’s memoir of life both inside the Warsaw ghetto and hiding beyond its borders.

It broadens our knowledge of social history during the period of the World War Two occupation and deepens our appreciation for the power of human hope and the enormous possibilities that can arise when the strength of familial bonds are combined with the will to live.”

The other significant fact of the story is that the two sons, whom Leokadia saved, later became in fluential Mathematics lecturersat California University in America. One became a veteran photographer and a cinematographer in Poland too.

Q. According to Leokadia’s introduction to the book, a part of it was written duringthe war while the other part was written after the war in 1966?

A: Yes, she began to write theseshocking experiences in 1943 at the request of her husband. He asked her to write down the horrendous experiences they faced from July 22, 1942 when the ghettos were demolished in Warsaw. He thought they wouldn’t survive the war.

Their friend Sigmunt Dobos also helped in this task by making a temporary table and installing a chair in their residence at 27, Belwedeska Street, Warsaw which was a tin-sheet workshop belonged to another friend’s father Antony Mihalsky. In this way, the first half of the book was written during the war.

When the war reached its climax, they had to flee from their residence in Warsaw. But before they left, they hid the manuscript and other valuable documents beneath soil keeping them inside a tin box. When the war was ended, they came up to the place and found the manuscript.

They moved to Paris where they spent one year, and then, moved to Venezuela to America. In 1966, when they resided in Arizona, US, her husband asked her to complete the manuscript which she started to write in 1943. This is how the book was written. It was published in English though it was originally written in Polish.

Q. How did you find this book to translate?

A: As a reader of Holocaust literature, I generally search the Internet and there I found this book. Then, theSarasavi Publishers where I work as a publishing consultant brought it here. The reason why I chose it to translate is its newness and the ratings it took among other books at the international arena.

Q. Though we had a 30-year battle against terrorism, we don’t see war literature in Sri Lanka?

A: If there are books on war in Sri Lanka, they have been written by pro LTTEers. We cannot see here war literature written from the people’s point of view.

Q. You began writing books recently?

A: My first book Appochchige Cinemawa (Our father’s Cinema) was published in 1972, but it was a critical writing booklet. I argued in the book that we don’t want subjective cinematic creations, such as Nidhanaya by Lester James Peris, instead we want creations which highlight social issues.

Lester invited me to discuss with him on cinema after reading that booklet. In 1981, I published my second book titled Satara Diganthaya (All over the place) which was the first published cinema script in Sri Lanka.

After that, there is a long gap, close to 40 years between my book publishing. My third book, Aronge Lokaya, a translation work was published in 2018.

The fourth book, another translation, Ginigath Sanda was published in 2019. You are correct. I venture into literature recently because of my profession of journalism as a sub editor.

Q. Is it difficult to write books when you are working as a subeditor rather than a news writer or a feature writer at anewspaper?

A: It is difficult to write books when you are working as a sub editor in a newspaper. I joined the Sri Lankadeepa at the Times of Ceylon Newspaper Company in 1978 as a sub editor. I was selected through a written examination.

Our translation skill was also judged. At the time, a sub editor had to provide foreign news too if necessary.

There were no Internet facilities. The only source was a ’ticker machine’ which gave us prints (roller papers) of Reuter and AFP news by ticking every second. We had to translate foreign news and take them for recast within a short time. I joined the Sunday Diviana newspaper in 1981.

Q. Haven’t you got a chance to write during your journalistic career?

A: While I was working at Sri Lanka deepa as a sub editor, I joined the Surathura, a cinema tabloid published by the Times group. When the then editor Athur U. Amarasena moved to another cinema paper, I became the editor of the Surathura.

There,I began to write. I wrote an investigative article on Rukmani Devi when she died in a car accident in 1978. I went to Negombo to find information for the article along with Camilus Perera and Deegala Mudiyanse. When I joined the Silumina newspaper at Lake House I once again started to write.

Q. When you were working at the Divaina newspaper, there were many writers around you?

A: Yes, Dayasena Gunasinghe, Sunil Madawa Premathilake, Chandrasiri Dodangoda, Karunadasa Suriyaarachchi were there, but that time was not conducive to write.

Many youths, artistes, journalists, politicians and people were killed in cold blood. I remember the day Vijaya Kumaratunga was murdered. I was in charge of the Colombo edition of the Divaina.

It was a heart rending experience to me to edit the paper as Vijaya was also a friend of mine. When the Fort bus-stand bomb went off, I gave the heading as Pitakotuwa Ekama Amu Sohonak (A total cemetery at Colombo Fort).

The article was written by Dharman Wickramarathne. When you are working as a sub editor, the responsibility is much higher than that ofa feature writer or news writer, because you are always bound to a running belt. You are not free to write novels or short stories.