Religion, has and always will be, intrinsically linked to culture. Historically, this can be seen reflected in the ways that the unifying effect of religion affects and forms the cultures that it spreads to. But also, it can be understood how over time, differing cultures observing the same religions have diverging beliefs, practices and observances. It has been said that the way of life, or the culture, of a people influences the approach to religions and that in turn, religion and the people’s attitudes towards it influences their culture. This cannot be clearer than with the flexible, almost random approach to religion that Japan has relative to everywhere else.

At the centre of Japan’s religious system is Shintoism. While most who have only a peripheral knowledge of Japan might think of it as an entirely Buddhist nation, what they believe to be a more extravagant form Buddhism is actually Japan’s very own indigenous religion, Shinto. While in modern times they refer to Shintoism as a religion for simplicity’s sake, historically it is a little too complex to be so easily categorised.

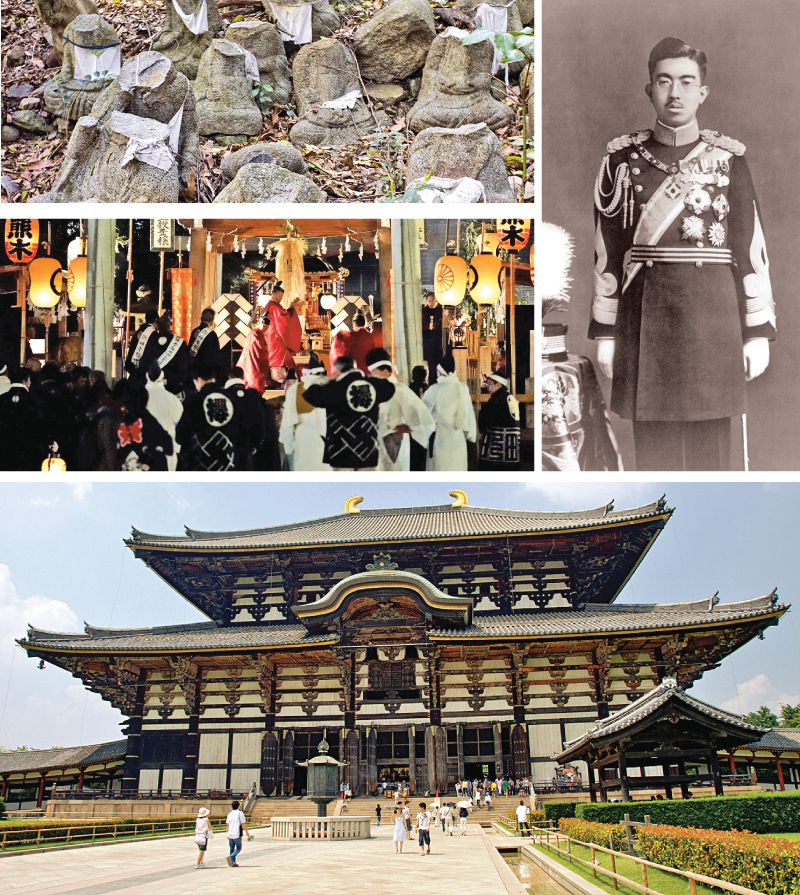

As a polytheistic nature religion, Shintoism is almost like a catch all category for the Japanese belief of gods, or Kami, which inhabit all things. With no single creator or doctrine, Shintoism varies greatly in differing parts of Japan, though it has become more homogenised in recent times. Unlike other, more traditional religions like Buddhism or Christianity, there is no moral code to follow beyond reverence for the Kami and rituals that express this reverence.

As a hazardous mountain country subject to great many natural calamities like earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and typhoons, Shintoism rationalises these disasters as the acts of vengeful Kami and rituals are performed to appease these gods. Other, more benevolent Kami were worshipped for the prospects of good fortunes. Together, it is said that Shintoism believes in the existence of at least eight million of these Kami and the practice of worshipping this massive pantheon is in fact a reflection of the inherent pragmatism of the Japanese, focusing on adapting to the sometimes harsh requirements of life.

Core tenets

On the other hand, Buddhism, the other major religion in Japan, emphasises the idea of transcending beyond life. While the core tenets of these two religions ways seem contradictory, Buddhism is actually practised quite commonly alongside Shintoism in almost perfect harmony. Japanese religion is highly pluralistic in practice and it is normal to practice multiple religions simultaneously. When Buddhism was first introduced to Japan from China in the sixth century, its popularity exploded, Bhikkus were explaining that the Kami were also trapped in Samsara needing enlightenment to escape it. This explanation would often be challenged by Shinto priests, who instead of rejecting Buddhism, said that the Kami were Buddhas who protected and propagated Buddhism, an explanation that actually fit well into the Mahayana sect of Buddhism that came to Japan.

Eventually, a compromise was reached with some Kami being integrated into Buddhism while others were explicitly separate from it. This was more a political rift than a religious one, built up over centuries of resentment, the disastrous result of which was the haibutsukishaku, the abolishment of Buddhism, during the Meiji Restoration during the late 1800s. This led to the destruction of over 40,000 Buddhist temples and the complete separation of Buddhism from Shintoism, before which, the two were so linked that most were not even aware of the difference. However, Buddhism survived and continues to be followed alongside Shintoism, though many areas of Japan do not as a result of the abolishment.

This flexibility in beliefs might not be immediately problematic and even quite beneficial but historically, politics and authority has taken advantage of this flexibility to manipulate the people and gain power. The most egregious example being that of the public being led to believe that the Emperors were descendants of the Creator God, Amaterasu, something that was taken full advantage of during World War 2.

Fanatism

Showa Era Emperor Hirohito was touted as divine and that fighting to the death in his name was the duty of the Japanese. This fanatism led to the atrocious and tragic lengths every citizen and soldier were willing to go for their God Emperor. After Japan’s defeat, the Emperor delivered the Ningen-sengen, or the Declaration of Humanity, in which he denied being a living god.

In modern times, Japan is more secular than ever with a majority of people being either non-religious or only casually religious. After the war, there was a mass abandonment of traditions of Japan in favour of modernising. While Shintoism gave reasonsfor many things in the past, it was its relationship with Buddhism that gave the Japanese much of its spiritual identity. After the abolishment of Buddhism, though it still remains today, religion did not quite recover from the consequences. As things are, religion is fractured in Japan, and is in need of immediate reform.