As Vladimir Nabokov says of Franz Kafka, “He is the greatest German writer of our time”. Yes, there is no argument about that. He is the most powerful writer in the 20th century despite the fact that he was unable to establish a name as a writer in his life time. When we look at his life story, we can understand how isolated and moving it was . Once well-known French writer François Mauriac said Kafka’s life was more interesting than his writings.

Kafka was born of Jewish parents in Prague in 1883. The family spoke both Czech and German; Franz was sent to German-language schools and to the German University, from which he received his doctorate in law in 1906. He then worked for most of his life as a respected official of a state insurance company (first under the Austro – Hungarian Empire, then under the new Republic of Czechoslovakia). Literature, of which he said that he ‘consisted’, had to be pursued on the side. His emotional life was dominated by his relationships with his father, a man of overbearing character, and with a series of women.

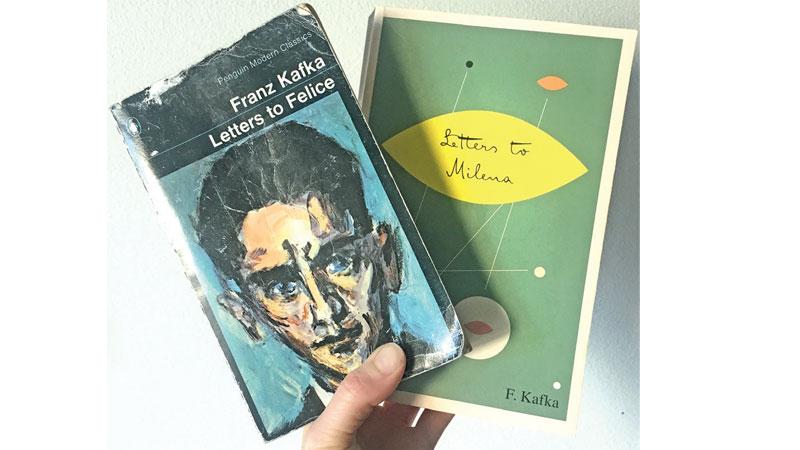

Mainly, Kafka had three women relationships, of them the first was with Felice Bauer from Berlin, to whom he was twice engaged. The Second relationship was with his Czech translator, Milena Jesenská-Pollak, to whom he became attached in 1920. And the other affair was with Dora Diamant, a young Jewish woman from Poland in whom he found a devoted companion during the last year of his life. When these relationships were active, they had exchanged many letters between them. Though we cannot find the letters these women wrote to Kafka, (apparently destroyed by them), we have a large number of Kafka’s letters to them. Letters to Milena is a book compiled by the letters he wrote to Milena Jesenská, first published in 1953 by Martin Secker & Warburg.

When the correspondence took place, Milena was twenty three years old. At that time she lived in Vienna and he lived in Prague, and during which time her marriage was slowly falling apart too. She recognised Kafka’s writing genius before others did, so she asked his permission to translate his short story The Stoker from German to Czech. Such a simple request and formal demand very soon turned into a series of passionate and profound letters that Milena and Kafka exchanged from March to December 1920. Kafka often wrote daily, often several times a day. This is what he tells her: “and write me every day anyway, it can even be very brief, briefer than today’s letters, just two lines, just one, just one word, but if I had to go without them I would suffer terribly.”

Actually, these letters reveal Kafka’s private life more than any other writing by him. He writes as, “I am constantly trying to communicate something incommunicable, to explain something inexplicable, to tell about something I only feel in my bones and which can only be experienced in those bones. Basically, it is nothing other than this fear we have so often talked about, but fear spreads to everything, fear of the greatest as of the smallest, fear, paralysing fear of pronouncing a word, although this fear may not only be fear but also a longing for something greater than all that is fearful.”

And he writes, “I’m tired, can’t think of anything and want only to lay my face in your lap, feel your hand on my head and remain like that through all eternity.”

Following are some of the quotations taken from the Letters to Milena:“In a way, you are poetry material; you are full of cloudy subtleties I am willing to spend a lifetime figuring out. Words burst in your essence and you carry their dust in the pores of your ethereal individuality.”

“Written kisses don’t reach their destination, rather they are drunk on the way by the ghosts.”

“Do you know, darling? When you became involved with others you quite possibly stepped down a level or two, but if you become involved with me, you will be throwing yourself into the abyss.”

“When one is alone, imperfection must be endured every minute of the day; a couple, however, does not have to put up with it. Aren’t our eyes made to be torn out, and our hearts for the same purpose? At the same time it’s really not that bad; that’s an exaggeration and a lie, everything is exaggeration, the only truth is longing. But even the truth of longing is not so much its own truth; it’s really an expression for everything else, which is a lie. This sounds crazy and distorted, but it’s true. Moreover, perhaps it isn’t love when I say you are what I love the most - you are the knife I turn inside myself, this is love. This, my dear, is love.”

“Sleep is the most innocent creature there is and a sleepless man the most guilty.”

“I am dirty, Milena, endlessly dirty, that is why I make such a fuss about cleanliness. None sing as purely as those in deepest hell; it is their singing we take for the singing of angels.”

“Sometimes I have the feeling that we’re in one room with two opposite doors and each of us holds the handle of one door, one of us flicks an eyelash and the other is already behind his door, and now the first one has but to utter a word ad immediately the second one has closed his door behind him and can no longer be seen. He’s sure to open the door again for it’s a room which perhaps one cannot leave. If only the first one were not precisely like the second, if he were calm, if he would only pretend not to look at the other, if he slowly set the room in order as though it were a room like any other; but instead he does exactly the same as the other at his door, sometimes even both are behind the doors and the beautiful room is empty.”

“I want in fact more of you. In my mind I am dressing you with light; I am wrapping you up in blankets of complete acceptance and then I give myself to you. I long for you; I who usually long without longing, as though I am unconscious and absorbed in neutrality and apathy, really, utterly long for every bit of you.”

“I’m thinking only of my illness and my health, though both, the first as well as the second, are you.”

“Nor is it perhaps really loves when I say that for me you are the most beloved; In this love you are like a knife, with which I explore myself.”

“I can’t think of anything to write about, I’m just walking around here between the lines, under the light of your eyes, in the breadth of your mouth as in a beautiful happy day, which remains beautiful and happy, even when the head is sick and tired.”

“Milena - what a rich heavy name, almost too full to be lifted, and in the beginning I didn’t like it much, it seemed to me a Greek or Roman gone astray in Bohemia, violated by Czech, cheated of its accent, and yet in colour and form it is marvellously a woman, a woman whom one carries in one’s arms out of the world, and out of the fire, I don’t know which, and she presses herself willingly and trustingly into your arms.”