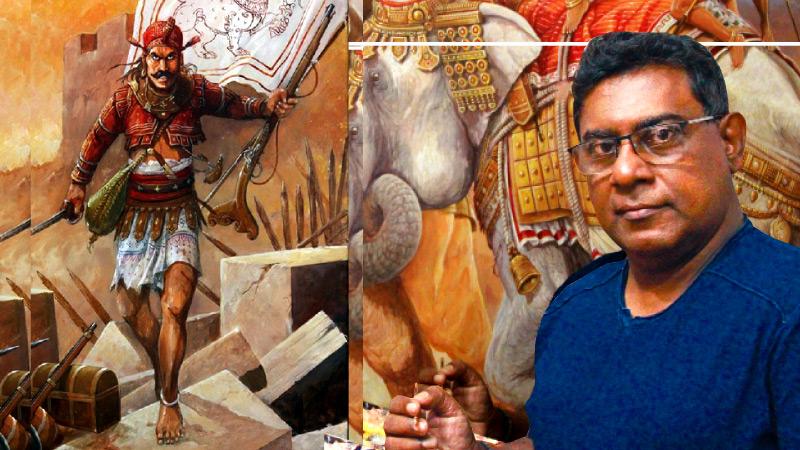

The history of Sri Lanka is rich and diverse. Ancient architecture indicates that we possessed advanced knowledge on irrigation and infrastructure. Some of our monarchs of the past have shown great leadership and some have not. However, there are only a handful of people who are truly informed of the intricate details of our glorious past. One of them happens to be artist and environmentalist Prasanna Weerakkody.

Born in Colombo to a family of artists, Prasanna Weerakkody has understood art as a form of language. He divulges generously, “Both of my parents were artists and art teachers. My father Kalasuri Ariyawansa Weerakkody was a painter and sculptor. He was also an art director. He was involved in films such as Gamperaliya, Sandeshaya and more. He has done about 17 films. My family was surrounded by art. My mother also being a teacher herself used to get us to draw on the floor (not on the walls) and then she later after we were done, she would mop the floor. It was good arrangement”.

Born in Colombo to a family of artists, Prasanna Weerakkody has understood art as a form of language. He divulges generously, “Both of my parents were artists and art teachers. My father Kalasuri Ariyawansa Weerakkody was a painter and sculptor. He was also an art director. He was involved in films such as Gamperaliya, Sandeshaya and more. He has done about 17 films. My family was surrounded by art. My mother also being a teacher herself used to get us to draw on the floor (not on the walls) and then she later after we were done, she would mop the floor. It was good arrangement”.

Art to visual storyteller like Prasanna must make the viewer feel. “I would say that art is something that would qualify or impact the viewer in some way. For example, people view history in a certain way. However once they see my work, it changes their thinking. Art should change the way people view things. It has to evoke something”, he says.

Tracing his passion for art, he thoughtfully ponders and replies. “We always had access to paint and other art material. I never went to a formal art school. My father was a hobby historian and he was a good narrator of it. He used to make us feel like we were living in that era! However I am also interested in wild life. Therefore, my initial work was a lot of wildlife paintings and I had a made a name in the field as a wildlife artist”.

Subsequently through his own interest, Prasanna started researching about Sinhalese warriors and armour. He vigilantly translated his findings in to paintings. “My exhibition in 2002 had a few of these paintings along with many of wildlife works. The reception the historical paintings received was tremendous and I was inspired. That’s when I embarked on my transition from wildlife paintings to historical ones” he clarifies.

Interestingly, Prasanna’s creative process is of two fold. One is the natural inward inspiration or inclining to draw which every artist has and the other in his particular case is external knowledge. “Basically I go through my history references. You suddenly read a sentence ‘Panduakabhaya had a white horse with red legs’ and it sticks in your head. Then you refer up more. And once I have enough of information I start painting. I work parallel on a few. Some of my murals take around four years to complete. So it is good to take a break from it and start on something else and the return to it. I am a slow painter. I prefer to take my time and complete the work”.

Interestingly, Prasanna’s creative process is of two fold. One is the natural inward inspiration or inclining to draw which every artist has and the other in his particular case is external knowledge. “Basically I go through my history references. You suddenly read a sentence ‘Panduakabhaya had a white horse with red legs’ and it sticks in your head. Then you refer up more. And once I have enough of information I start painting. I work parallel on a few. Some of my murals take around four years to complete. So it is good to take a break from it and start on something else and the return to it. I am a slow painter. I prefer to take my time and complete the work”.

The challenges he faces as an artist is of a great relevance to us natives. “As an artist of history, I need portals to travel back in time. One of them is of course text references. Then the most significant ones are artefacts and paintings - that is mainly temple art. Some of these paintings have been destroyed. The Thivanka Pilimage for instance is as important artistic wise as the Sistine chapel. Some of the best work of the Polonnaruwa Period was stored there. The archaeological department let it get wet and the work has been destroyed. This is not only a personal challenge but a national crisis!” It is indeed sad that such precious masterpieces have been treated with callousness from those who are entrusted to protect it. Enhancing the sentiment further, he adds “Also I have noticed that the restorative artists have eroded the drawing techniques that the ancient artists have used”

Viewing his work, any person from any walk of life can easily be mesmerised by its vivid description. It takes a special kind of skill to execute such work. Rather than utilising his gift to reveal a private journey, he chooses the past as his motif. He excitedly responds, “I saw history in a way that most people didn’t. The way I see it through many references - my visualization of it was different. For instance – the Sinhala warrior most often has been portrayed with only a few items on him and a sword. But when you research you find out that he wore more, there are detailed descriptions of armour, jewellery, and costume. It is like a Hollywood imagery. I had to bring that to the table!”

Presenting a broader view on his thoughts, Prasanna imparts an important case in point. He states knowingly, “At the same time, the Portuguese arrived in Sri Lanka they also had arrived in South America. They completely destroyed the culture there and the people there were also not strong enough to face them as they were unexposed to new technologies. Sri Lanka however had been an international hub from ancient times and therefore they had evolved with time. So we were successfully able to face the Portuguese, when they arrived”.

If you thought that we had state of the art machinery, Prasanna eloquently confirms it. “Globally guns were started to have been used around 1550 and we too had that armed weapon technology which was given to us from the Mogul Empire. This is a fair analysis because our guns were called ‘bondi kula’ and the Arab guns were referred to as bandos”.

Prasanna actively plays two roles. “I am involved in two lines of work. I am an artist and I am also a marine environmentalist and a conservationist”, he admits proudly. Most of the time, he finds himself unable to separate the artist and the environmentalist in him. He points out that the Human Elephant Conflict from the perspective of both. Employing history as evidence, he firmly reports that the Asian elephant is animal that can be tamed and that this is something our ancestors knew and did.

“From the Anuradhapura era to the Kandyan era, elephants have been portrayed perfectly in monuments and paintings. They were part of our everyday life. It is fair to say that they were as domesticated as dogs are nowadays. But today the close association, we had with elephants has evaporated. The elephant culture we have today isn’t what we had then.

“From the Anuradhapura era to the Kandyan era, elephants have been portrayed perfectly in monuments and paintings. They were part of our everyday life. It is fair to say that they were as domesticated as dogs are nowadays. But today the close association, we had with elephants has evaporated. The elephant culture we have today isn’t what we had then.

Never was the elephant chained. If you look at temple murals the elephant never had a chain. Look at how we treat them now? Also the old mahout tradition has gone. We have lost the human elephant tradition”.

Disappointed with the position of art in the country, Prasanna speaks and questions coherently. “I think in Sri Lanka art has not been given its due value. I mean other areas of the arts, such as films, music and drama have been given a place, as opposed to art that has been dismissed. There was an incident that took place along with the recent elections. Most of my work had been copied and painted up on walls publicly at least 75 times (it was apparently a part of some nationalistic movement). How does the new generation use creativity? Do they not have original thinking? People have started to acknowledge copying as a new art form. I’ve even been asked to copy my own work. But I don’t do that. How can creativity grow if we keep copying?”

Besides this, he suggests both the government and the education system to support and nurture talent. “Art materials are expensive.

Maybe the government can reduce the tax on that. School education should focus more on developing creativity. They should utilize more mediums other than pastels. The students should be given adequate time to finish a work. It shouldn’t be rushed”, Prasanna advises.

Leaving the past momentarily, Prasanna contemplates on the future. He will obviously continue to do what he does and a little more. He confides, “I am hoping to launch a coffee table book with a detailed description of each of my paintings. I have been involved in a few movie productions. I would love to do more and be more involved in historical movies that are being made here”. Undoubtedly one has to agree that the epic chronicles that are made for the local silver screen could use more visual accuracy.

Prasanna concludes with a sincere affirmation. “History was always very interesting for me. But my history books weren’t. History education in school was made boring. Kids weren’t or aren’t interested in our local history. There’s no drive to engage their interest and these kids are knowledgeable. They would know Robin Hood as opposed to Dutgamunu.

This is because Hollywood has painted a visually stimulating picture of Robin Hood. But the thing is our history is as visually effective. That’s why I do what I do. I want to do my bit and show this. I want to make history more accessible to kids!”