Kabuki, the 400-year-old traditional Japanese performance art of song and dance, is the most famous of the three major classical theatres, alongside the less well-known Noh dance dramas and Bunraku puppet performances. Its worldwide reputation and cultural importance granted it the honour of being officially inscribed in the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008.

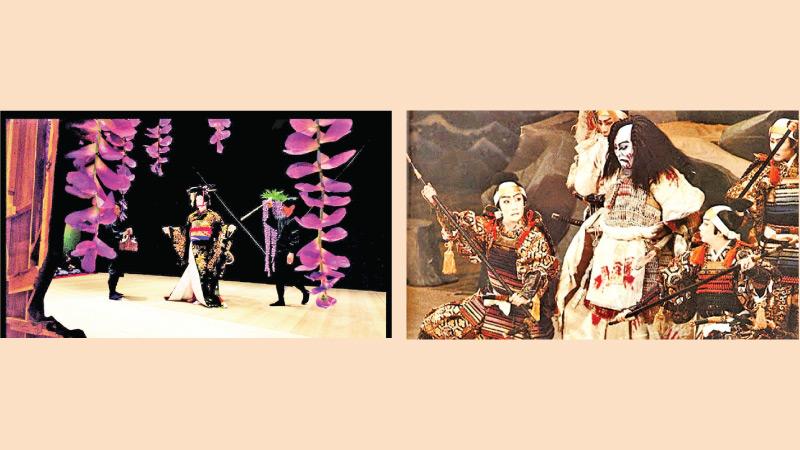

Flourishing even today, Kabuki performances emphasize outlandish visual spectacle; blending song and dance with highly stylized costumes, lighting, props and set design to deliver a grandiose and spectacular show. Kabuki shows valued looks over story, a Japanese concept that is well and truly alive in Japan with subcultures like Visual Kei prioritizing looking visually striking over anything.

As a primarily visual medium, Kabuki actors told their stories with exaggerated movements to convey meaning to the audience, so that it allowed even those who didn’t understand what was being said, to comprehend what was happening. This was important as they used an archaic form of Japanese in their performances that even the Japanese wouldn’t normally know. Hence, Kabuki plays were more suitable for actors to demonstrate their talents and skill on an ornately designed stage than they were a type of literature.

Actors were usually descended from a lineage of Kabuki actors and the stage names they took passed down from generation to generation, so taking them up also meant carrying the expectations of the spirits of the previous holders of that name. Stage names in Kabuki are representative of a certain role and acting style and it is common for actors to change their stage names at grand naming ceremonies held before audiences known as Shumei, multiple times throughout their career to signify their personal growth as an actor.

It is interesting to note that during performances, stagehands would appear on stage to hand actor’s props or otherwise assist in making things go smooth. They are called kurogo and they would dress in all black to indicate to the audience that they are an element to be ignored on stage. It is theorized that it is for this reason that the modern stereotypical convention of dressing Ninjas in all black came to be, unlike the historical reality of them actually dressing like civilians to better fit in.

Plots in Kabuki told stories that fell into either the historical play (Jidaimono) or the domestic play (Sewamono). A strange and unique feature of the Kabuki theatre is that the stories told were often only a part of a complete story, usually the best part, so that to fully enjoy it, one must have already been aware of the tale being told. Performances, though they usually involve tragic endings, finish off with lively dance finale (Ogiri Shosagoto).

Originally,Kabuki was a solely female production. Invented by Shinto priestess Izumo no Okuni in the early 1600s, she gathered local misfits and prostitutes to form all female troupes who played both, male and female roles. Early Kabuki performances were parodies and were both witty and suggestive. Popular in the red-light districts of Kyoto, the practice was closely associated with prostitution as performers would often engage in it as well. The moral backlash resulted in a ban on female performers and young boys took over. However, this was also suppressed as young boys also tended to be prostitutes and so, the current practice of adult men taking up the roles of both women and men was born.

Kabuki used to be bizarre and eccentric, an aspect that its name is thought to be derived from, Kabuku, meaning to behave oddly. Overtime, Kabuki plays grew in sophistication and became more subtle, but not much, still very much unrestrained. This is in contrast to Noh, the other great Japanese theatre that was exclusive to nobility and was appropriately elegant and subtle in its performances.

By the eighteenth century, Kabuki became the people’s theatre, providing great insight into what life in Japan was like at that time.

Historic events of the time became legendary plays, such as the popular tale of 47 Ronin, Chūsingura, a faithful retelling of the band of samurai who avenged their murdered lord followed by their punishment of ritual suicide. Chikamatsu Monzaemon, a playwright of such renown, he was often compared to the likes of Shakespeare, wrote many plays detailing lovers’ double suicide plots, most of it based on actual suicide pacts made between real life lovers.

Post World War II was a difficult time for Japanese culture. The US occupation of Japan meant that the nation underwent a great westernization, and many embraced this change, abandoning the old ways, including Kabuki.

However, a resurgence in the Kansai region led by director Tetsuji Takechi reintroduced the art back into public consciousness and became the most famous of the traditional Japanese performance arts. Revitalized, Kabuki took on a more modern form, with Kabuki cinema, overseas performances and even adapting foreign works such as Shakespeare into the Kabuki format.