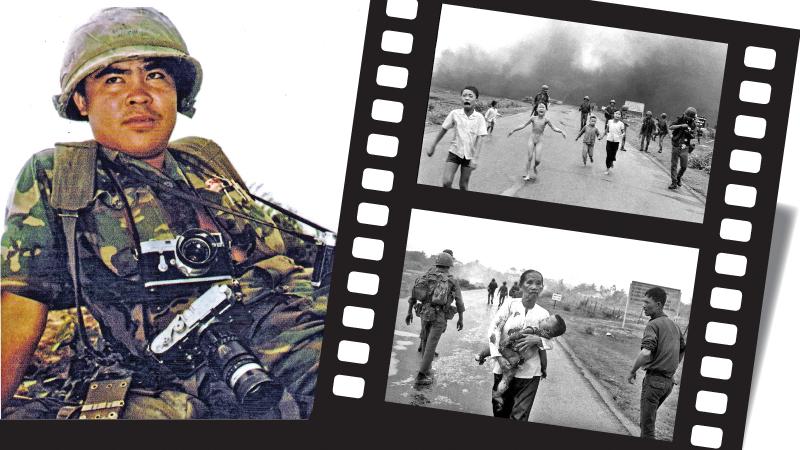

In a world where images have the power to transcend time and sear themselves into our collective memory, few photographs have achieved the level of impact as Nick Ut’s iconic “Napalm Girl” image. The lensman behind this arresting snapshot, Huynh Công Út, professionally known as Nick Ut, is more than just a photographer – he is a witness, a storyteller, and an agent of change.

Born on March 29, 1951, Ut’s journey into the world of photography was set in motion by a personal tragedy – the loss of his brother, who was also a photographer with the Associated Press (AP). Inspired by his brother’s commitment to using photography as a tool for social justice, Nick Ut set out to carry on his legacy. Guided by the mentorship of renowned photojournalist Horst Faas, Ut embarked on a path that would lead him to capture some of the most pivotal moments in history.

In 2012, Ut became the third person inducted into the Leica Hall of Fame for his contributions to photojournalism. A collection of his images captured for the past 50 years called “From Hell to Hollywood” is now a world-wide travel exhibition. This exhibition was opened at the Lotus Tower, Colombo on August 19, the World Photography Day, in the presence of foreign and local photographers.

A path forged by resilience

Ut’s entry into the realm of photojournalism was not without challenges. Denied a job due to his age and persistence, he refused to be deterred. His determination paid off when, in 1966, he was finally welcomed into the ranks of AP photographers.

Ut’s journey began humbly – in the darkroom of the AP office in Saigon. “My brother, who worked for the Associated Press before me and whose mentor was the famous Horst Faas, motivated me to become a photojournalist. My brother showed me how to use a camera. He told me before he died while covering a conflict, “I hope one day you have a picture that stops the war.”

Nick Ut meets the Napalm Girl later in America

|

Horst was furious when I chose to follow in my brother’s footsteps. He said that he did not want to have to contact my mother and inform her that a second son had died. I informed him I was aware of the risk and that it was entirely my decision. I begged the AP for a job they said I was then too young. I wasn’t even 16 at the time. I continued phoning to let them know I needed a job. Then they invited me in. They finally hired me in 1966. Then I began learning darkroom work at Saigon’s AP darkroom. I enjoyed the darkroom since there was nowhere to learn photography in Vietnam”, Nick said with sparkling eyes.

Capturing humanity amid horror

Ut’s lens was not confined to the darkroom. It roamed the streets, capturing snippets of life amid the chaos of war. The vivid recollections of his drive to Trang Bang in 1972 underscore the reality of conflict. Rows of lifeless bodies lining the road and refugees fleeing their homes formed the backdrop of a scene that would forever change Ut’s life.

Amid the devastation, he trained his camera on a young girl, Phan Thị Kim Phúc, running naked and terrified, her innocence juxtaposed against the backdrop of destruction. “What I am certain of is that it represents the utter horrors of war, as shown by a little child running nude in the midst of destruction and death. On June 7, 1972, I learnt about the combat in Trang Bang, a little town 30 miles Northwest of Saigon. I recall witnessing rows of dead at the side of the road and hundreds of people fleeing the area when I drove to Trang Bang the next morning. I ultimately arrived at a community that had been completely decimated by days of bombardment.”

“Residents were so exhausted by the continual fighting that they evacuated their town, seeking refuge on the streets, under bridges, or anywhere they might find a moment of peace. I had the photographs I thought I needed by lunchtime. I was about to depart when I noticed a South Vietnamese soldier drop a yellow smoke bomb near a clump of buildings, which acted as a target signal. I took out my camera and recorded an image of a jet dumping four Napalm bombs on the village a few seconds later.”

“We did not know if anyone had been hurt when the explosives exploded. The village had been deserted all morning. Many others, however, were sheltering in the local temple. We got closer and noticed people escaping the Napalm. When I saw a woman with her left leg badly burnt, I was appalled. I can still picture the old mother holding the baby who died in front of my camera and another woman carrying a young infant whose skin was peeling. I then heard a toddler yell, “Nong qua! Nong qua!” It’s too hot! It’s too hot! I gazed through my Leica viewfinder to see a young girl racing towards me after removing her flaming garments. I started photographing her.”

“She then shouted to her brother that she believed she was going to die and that she needed some water. I immediately put my cameras down to assist her. That was more essential to me than shooting more images. I poured water on her body to calm her off, but it just made her feel worse. I had no idea that you shouldn’t put water on who have been severely burnt. I loaded all the children into the AP van while still in shock and among the commotion of everyone yelling. The nearest hospital Trang Bang, I drove them there. “I’m dying!” the girl screamed over and over.”

“I found out her name was Phan Thi Kim Phuc at the hospital. She received third-degree burns covering 30 percent of her body. The physicians were overwhelmed by the large number of injured troops and civilians who had already arrived. They first refused to admit her and directed me to transfer her to a larger hospital in Saigon. But I knew she’d die if she didn’t seek assistance right away. I gave them my press badge and told them, “If one of them dies, I will make sure the whole world knows.” They then led Kim Phuc inside. I never looked back on my decision.”

“Kim Phuc was only permitted to come home for one day after spending a year in the burn unit. That day, I went to see her, bringing toys and books from the Red Cross and fruits and cakes from the AP office. Kim Phuc was cheerful despite the fact that her family’s home had been destroyed.”

The Napalm Girl photograph, often hailed as one of the most powerful images of the 20th century, encapsulated the horrors of war while simultaneously revealing the resilience of humanity.

Ethics in the midst of tragedy

Ut’s photograph, however, faced its own journey to the world’s eyes. Rejected initially due to concerns over nudity, it took the conviction of AP figures such as Horst Faas and Peter Arnett to ensure its publication. The photograph was not a mere spectacle; it was a truth that demanded to be seen. Its veracity challenged even the highest echelons of power, with President Nixon speculating about its authenticity. Yet, the image endured as a testament to the power of photojournalism in shaping public discourse.

Ut said, “As soon as I clicked the shutter, I knew I had something special”. It took Horst Faas to fight for it to be published, but fight he did… and the rest is history. The first AP picture editor who had seen Ut’s developed image rejected it, fearing that Kim Phúc’s nudity meant it could never be published in the US”. It then went from Saigon to Tokyo to New York by radiophoto transmitter, and soon was horrifying the world, much to the discomfort of the US military and President Nixon’s administration.

Nixon even considered passing Ut’s picture off as fake news and is heard speculating on one of the fateful White House tapes that the photo was ‘fixed’. Thankfully, the veracity of the image was proven, and even more thankfully, Kim Phúc (now known as Phan Thị Kim Phúc) survived her life-changing injuries and went on to be a UN Goodwill Ambassador.

For Ut, each photograph carries a weight – a story waiting to be told. His journey through conflict zones and dangerous environments has taught him the delicate balance between capturing truth and respecting human dignity. He navigates the fine line between exploitation and empathy, capturing the reality of suffering while ensuring that his subjects are treated with the respect they deserve. It’s a delicate dance, one that Ut executes with reverence.

Through the lens of change

As technology evolved, so did Ut’s approach to storytelling. The advent of digital photography allowed him to share moments in real-time, sending images that spoke volumes across the globe in an instant. In a world fuelled by rapid digital sharing, war photography remains a catalyst for shaping public opinion and influencing policy decisions. Every photograph becomes a clarion call for change, urging us to confront the stark realities that persist.

“I used the Nikon M and the Leica M2. The AP then gave me the M2, M3, and two Nikon Fs, so I carried four cameras whenever I went on an assignment. Then I started travelling and covered Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos. I would travel by motorcycle and go to assignments every day, war every day. It was crazy. I did this until 1975 and the fall of Saigon,” he said.

“Viewing the horrors of war in person provides a perspective that few can ever experience. At the same time, amid the death and destruction of war, the resiliency of humanity shines through — and I am reminded of that each time I see a picture of Ukrainians supporting their fellow citizens through this challenging time.

It is with this optimism in my heart that I hope that when Russian soldiers come upon an innocent Ukrainian girl in need of help, they feel the same impulse I once did, put their guns away and take care of a fellow human. I am proud of my photo and the emotions and conversations it created around the world. Truth continues to be necessary. If a single photo can make a difference, maybe even help end a war, then the work that we do is as vital now as it has ever been.”

A message to the future

To aspiring photojournalists seeking to make a positive impact, Ut’s advice is candid: embrace the challenges, for it’s in those moments that the most meaningful stories are born. Learn from the past, recognising the lessons of photographers such as Kevin Carter and the profound responsibility that comes with bearing witness. The tools of the trade have evolved, but the essence of photojournalism remains unchanged – it’s about capturing stories that need to be told.

“Forty years ago, combat photographers carried many heavy cameras, almost like a hundred rolls of film. Negative, black and white, slide film all in a big bag. Today, it’s easier. You just carry two cameras and a laptop. You can send pictures right away, so easy.”

In a world rife with conflict and complexity, Nick Ut’s journey from a young boy in Saigon to an acclaimed photojournalist serves as a reminder that every photograph carries the potential for change. From the Napalm Girl to the resilience of people in the face of adversity, his lens has captured a spectrum of emotions that define our shared human experience.

As the world looks through his eyes, it’s undeniable that the power of an image lies not just in its pixels, but in the stories, it tells and the conversations it ignites.