It is not a common occurrence when one comes across a work of short fiction that presents in its very simplicity of structure a depth that leaves the reader speechless. Singaporean fiction writer Jeremy Tiang’s short story ‘1997’ creates an impact that makes the word ‘amazing’ starkly inadequate to describe the overall brilliance of the work.

I do not by any means make claims of being the most voracious reader in Sri Lanka. And therefore dear reader, please take these perspectives for what they seem to be worth in the context of your own scope as a fiction reader.

I do not by any means make claims of being the most voracious reader in Sri Lanka. And therefore dear reader, please take these perspectives for what they seem to be worth in the context of your own scope as a fiction reader.

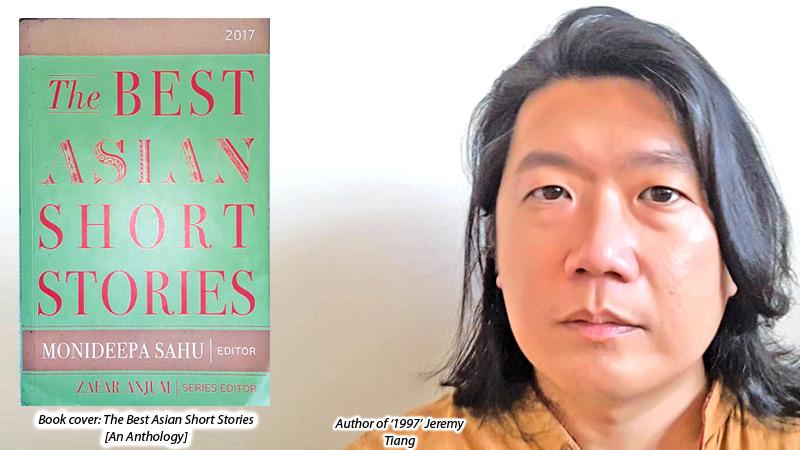

‘The Best Asian Short Stories’

I read Tiang’s ‘1997’ in the short fiction anthology titled ‘The Best Asian Short Stories’ (2017), published by Kitaab International, Singapore and edited by Monideepa Sahu.

Originally published in ‘The Brooklyn Rail and Stand’, Tiang’s ‘1997’ rings out a sharp message pertinent to the world of today in more than one way. Food security is of paramount importance to humankind, and megalomaniac authoritarians when they claim power can become blind to the needs of the poor and deprived, creating mass silent suffering.

Sri Lanka can relate to this reality all too well when looking back on the past couple of months that caused the current situation of political and economic instability in the country.

From its basis of wisdom and the connection made to the present, I say without hesitation Tiang’s ‘1997’ is a story the world at large needs to read. A story that should be translated to every language in which printed material is produced. The importance of this work of literature cannot be overstated in my opinion.

An elder’s oral narrative

When I read Tiang’s ‘1997’ I realised I had encountered a whole new level of brilliance in the art of short fiction. Simple, uncomplicated, unpretentious and almost infinitely deep and capable of an iceberg like impact.

Simple imparting of wisdom through a personal account of an unspoken past. An unhealthy past from which the present can learn to avoid a fearful future. While reading it I could not help hear echoes of the Japanese TV series ‘Oshin’ which many Sri Lankans enjoyed back in the 1980s.

Stories of hardship and triumph experienced by a generation of elders recalling and reliving those memories as oral narratives to their heirs so that the journey of a nation is preserved in the memory of their successors.

‘1997’’s setting is a dim sum restaurant in Hong Kong; a country at the threshold of being handed back to communist China by the British as the ‘days of British dominion’ are fast coming to an end.

The year 1997 is round the corner. Hong Kong will soon be under the direct control and direction, and by that, the inevitable oppression, of communist Beijing’s ‘red mandarins’.

The speaker - narrator imparts wisdom from her life experience from childhood days on mainland China when Mao’s military mandarins unquestioningly executed disastrous economic policies that led to nationwide famine and mass starvation of the rural Chinese population.

Over a sumptuous lunch for two hosted by the narrator, she relives this past and imparts her wisdom for the good of her teenage blood relative seated at the table, her cousin’s daughter. Thus the narrator of the story, and its other silent character, indicated through the narrator’s words to be part of the scene of the story, are cousins once removed when viewed through English terms of kinship.

However Tiang, in keeping with the idea of using the English Language to convey terms of kinship in the Asian cultural context, ‘Asiatically’ positions them to be ‘aunt’ and ‘niece’. To the wider Asian readership after all that would be perfectly normal.

The narrator explains in simple terms and conversational tone the tides of disaster unleashed by an autocratic all knowing leftist megalomaniac – Mao Tse Tung. A reality about China that the narrator’s cousin once removed niece is not in the least aware of as she was born and raised in Hong Kong.

A country the teenager is not happy to leave for UK along with her parents simply because the British will leave and hand the country back to China as per the terms of the historical 99 year bilateral lease treaty.

The narrator thus gives the teenager a glimpse into the life that was never known to the younger generation.

A story with lessons on why political power in its absolute form when held by one man must be dreaded by the people under that rule.

To understand the weight of oppression Communists would not hesitate to impose on any and all obstructers and dissidents who may be a threat to their regime, let’s not forget that it was Mao who said “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.”

Impending global food crisis

The world is now on the brink of a global food shortage. Authoritarianism sprouts from different corners of the globe. Tiang’s story speaks on so many levels and brings out themes of security in manifold facets. Political security, food security, and emotional security, are touched on unfolding a heartbreaking story that has a chilling vein unlike any I have come across before. It is haunting.

A picture of frozen grief. A depth that is hard to define. At the heart of the story is one that speaks of how important family bonds are for individual survival and how deep the bonds between parents and children can be. A story that symbolically says that even while dead, a mother can still nourish her child.

The craft of Tiang’s literary cameo

The narrative form of the story is one that deserves comment from the point of understanding the craft adopted by Tiang to create this masterfully carved (literary) cameo. The form is of an oral / verbal monologue as opposed to an interior monologue. The narrator’s intended audience is her cousin’s teenage daughter, not the reader as is the case of an interior monologue.

Therefore, the text must be classified as an oral monologue. But while being an oral monologue it is not a soliloquy either. If it were a soliloquy, again like an interior monologue, the audience of the narrator would be the reader. Therefore, ‘a one sided conversation’ is what is narrated to the reader, in the form of an oral monologue.

As a country that has been historically and to this day predominantly Buddhist in many aspects of national life, Sri Lanka’s elected representatives cannot afford to overlook the significance of the Buddha’s words – ‘Sabbe saththa ahara thithika’, which translates to ‘All living beings subsist on edible food’.

Tiang’s ‘1997’ is a work of (short) fiction every Sri Lankan must read. A work that should be translated to Sinhala and Tamil as well.

When perusing ‘1997’ for its form and content it became quite apparent to me that this is a work that has immense potential to be adapted to both the screen and the stage.

A text that could be the basis for a work of Avant-Garde cinema or theatre. It could be adapted for performance on stage as a single speaker play, but not necessarily a solo performance, thereby not necessarily a single actor play.

A performance that shows the verbal narrator being the only ‘speaker’ in a dim sum restaurant at a table for two, while all others being physically visible and active while being verbally mute.

A work of theatre with that approach will preserve the textual vision of Tiang who has crafted the impact of the story as a narrative not of the more conventional prose form with dialogue interplay.

‘1997’ is a verbal monologue which ends with words of genuine familial love that simultaneously conjure potent symbolism conveying a chilling subtext.

Sri Lanka’s Colombo centric English theatre community has grown robustly with diversity over the past two to three decades. Several theatre companies that focus on experimental theatre have gained a notable following.

Could present day Avant-Garde theatre practitioners in Colombo consider ‘1997’ for adaptation to the stage? Perhaps Ruwanthie de Chickera of Stages Theatre Group, Ruhanie Perera and Jake Oorlof of Floating Space Theatre Co, Tasmin Anthonisz of Studiolusion or Nishantha de Silva and company of Anandadrama. I wonder?

A voice that must be heard globally

Connecting with Jeremy Tiang via Twitter I told him how much I loved his ‘1997’. When asked if performance rights to adapt his story to screen or theatre were agented, he said ‘no’.

Therefore, it is worth noting for filmmakers or dramatists, the opportunity to obtain adaptation rights for ‘1997’ directly from the author exists at present.

I have no doubt that ‘1997’ will have much success among theatergoers both in Sri Lanka and abroad should it deliver a performance that preserves the integrity of Tiang’s narrative vision of a fiction that speaks in a single voice.

A voice that has to be heard, and taken to heart, far and wide in these times of impending perils.