Lester James Peries would have become one of the country’s top journalists had he remained in the profession. After all, he was quite well established as an overseas correspondent for the Times of Ceylon when his true Line of Destiny came to light. Lester certainly had a way with words, but it soon became apparent that he also had a way with pictures – of the moving kind.

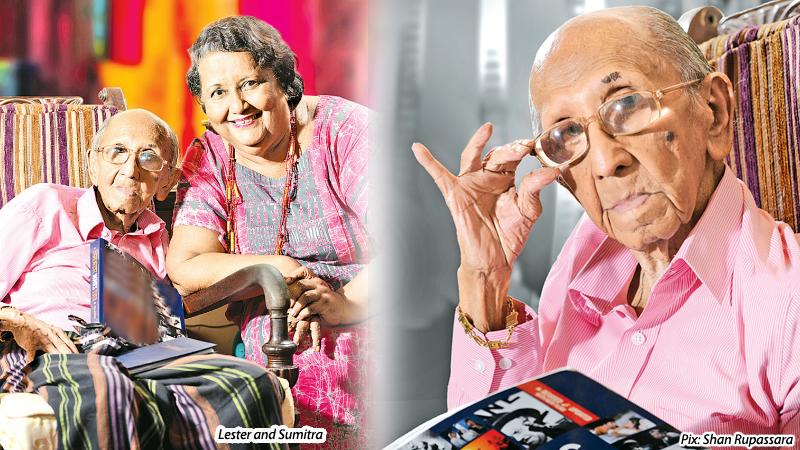

This is where he spent 50 years of his professional life. He had just celebrated his 99th birthday last month, surrounded by the people he loved and lived for. The overriding theme of all of Lester’s movies was just that - people. In fact, he once told an interviewer that while most other directors worked with symbols, he worked with human beings.

His very first feature Rekawa (Line of Destiny, 1956) became such a critically acclaimed movie (though it was a box office flop) mainly because it focused on the travails of villagers whose lives were far removed from the then formulaic films that were a cocktail of songs, fights and unnatural dialogue. Yes, Rekawa had songs, but they were completely indigenous and totally natural in the context they were shown on screen.

This was perhaps Lester’s biggest achievement – breaking the mould of the then Sinhala cinema which was a complete carbon copy of South Indian cinema. In fact, most Sinhala movies were shot in Indian studios, with very few outdoor scenes. On the other hand, Rekawa was shot entirely in location, which was a novelty in the 1950s even in Hollywood. Rekawa set off a chain reaction which saw many other directors follow Lester’s footsteps, if not quite with the same measure of aplomb.

Rekawa also had only a few “name” actors, which gave the film an added layer of authenticity, though it may have cost him at the box office with an audience accustomed to star power. However, the film was a worldwide sensation, having been nominated for a Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival that year. Lester later became a regular fixture at Cannes, the world’s most prestigious film festival which also held a retrospective of his films a few years ago.

Lester did cast almost all of Sri Lanka’s biggest stars from Gamini Fonseka to Malini Fonseka in his subsequent movies. While there are many directors who are in awe of the stars of their movies, with Lester it was the other way around. Lester was a walking encyclopaedia on film and it was a rare honour for an actor to be selected to play a leading character in a Lester James Peries movie. Veteran movie actress Iranganie Serasinghe recently told a TV interviewer that she was trembling with trepidation before facing the camera for the first time, but it was Lester who literally showed her the way and effaced any sign of fear. This is the story of many other actors who were guided by Lester who had the unique ability to extract every known emotion from his actors, including child actors.

Many of his films were eerily atmospheric and only a few other films made anywhere in the world can match that final stabling scene from the Nidhanaya (Treasure, 1972) for its sheer evocation of abject fear. (The one other scene I can think of is the shower stabbing from Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 masterpiece Psycho). Nidhanaya narrowly missed the Oscar nomination window but went to the Venice Film Festival in 1972 and became one of the ‘Silver Lion’ winners. From the start to the climax, Nidhanaya and his other movies engulfed the audience in a torrent of emotions ranging from sympathy to anger to hope.

Lester had the good fortune of having a good team who understood his every whim and every command. Editor Titus Thotawatte (who later went to become a famous director in his own right) and cameraman Willie Blake were two film craftsmen who knew what Lester wanted before even he could say it.

Some of Blake’s camerawork, framed initially in Lester’s mind’s eye, were so innovative for the day that film students are still studying them. He also pioneered innovative lighting techniques – some of his movies were shot with a single lamp.

Lester was no stranger to the movie camera from his younger days – he played around with an 8mm system gifted by his father and later made experimental short films during his stint in London with his brother Ivan, the well-known painter.

Lester was not a prolific director in the true sense of the word. But as they say, what he lacked in quantity, he made up for in substance. If one leaves out the five short films (which were excellent, of course), he made only 21 feature-length movies during a span of five decades. His first two outings Rekawa and Sandeshaya (The Message) were not very successful at the box office, but audiences warmed up to his unique brand of movies from his third feature Gamperaliya (Changes in the Village), which won him the Sarasaviya Best Director Award, his second and the Golden Peacock Award at the India International Film festival. (His first award was for Rekawa). Gamperaliya was shown at the Cannes Film festival in May 2008 under the French title Changement au village. Subsequently it went out on general release in several French cinemas. A French-subtitled DVD was also released in France.

Incidentally, Gamperaliya was the first in a trilogy and was followed by Kaliyugaya (1983) and Yuganthaya (1985). The long gap between the films helped to make them even more realistic, as many people went through the same generational and social changes. The three films are based on veteran author Martin Wickramasinghe’s trilogy of the same name, which follows the decline of an agricultural family and its transition to the new urban economy.

Gamperaliya, which starred Gamini Fonseka, Punya Heendeniya, Wickrama Bogoda and Henry Jayasena in the lead roles, was very well received by critics worldwide. Playwright Ediriweera Sarachchandra hailed the film saying “at last a Sinhalese film has been made which we could show to the world without having to hide our heads in shame. I want to say a great film has been made of a great novel.” British director Lindsay Anderson praised its “elegiac, near-Chekhovian grace.”

Major impression

Although Lester’s fame spread far and wide in the English-speaking world and also in France where most of his movies made a major impression, he made just one film in English, the God King (1975) which starred both local and foreign actors. Much later, his Wekande Walauwa (Wekanda Mansion, 2002), would become the first Sri Lankan submission in the Foreign Language Oscar category. The movie is adapted from Anton Chekov’s famous short story The Cherry Orchard and is set among the Sri Lankan elitist society. He also collaborated on some of his wife Sumithra’s movies, including her current release Vaishnawee, which is based on a story penned by Lester and was released on his birthday (April 5). The writer and journalist in Lester never left him, after all.

His earlier journalistic and writing career perhaps helped him to bring even complex books such as Gamperaliya to life. He knew exactly what should be left out from a book when it was adapted to the big screen and any changes that should be made. But mostly he tried to be faithful to the essence of the book. In the hands of his veteran scriptwriters, including, Dr. Tissa Abeysekara (himself a renowned director), this was very easily done.

Another one of Lester’s movies based on a book was Baddegama (Village in the Jungle, from the 1913 book of the same name by Leonard Woolf). Set during the British occupation of Sri Lanka, it told the story of villagers confronting many challenges under the yoke of colonialism. The 1980 movie also starred British science fiction writer Arthur C Clarke, who lived in Sri Lanka until his death in 2008, as Woolf. Beddegama was screened at the Cannes Film Festival in the Directors’ Fortnight section.

Among his other well-known works are: Delovak Athara (Between Two Worlds, 1966), Golu Hadawatha (Silence of the Heart, 1968, Sarasaviya Award for Best Director), Akkara Paha (Five Acres, 1969), Desa Nisa (A Certain Look, 1972), Madol Duwa (Mangrove Island, 1976, based on Martin Wickramasinghe’s bestselling novel), Ahasin Polowata (White Flowers for the Dead, 1978, Presidential Award for Best Director), Awaragira (The Sunset, 1995) and Ammawarune (Mothers, 2006). Interestingly, the screenplay of Golu Hadawatha, written by Regi Siriwardena based on the novel by Karunasena Jayalath, was translated into English and serialized in this newspaper at that time, which popularized the movie among English-speaking families as well.

Not many people know that Lester was a first-rate documentary film maker as well, which further grounded him in the realities of village and urban life that he portrayed in the feature films. None of his films were overtly political, but he did take a swipe at the class and creed structure every now and then. Lester made judicious use of music and songs in his movies, interspersed with long gaps of total silence where the pictures alone did all the talking.

Like some of the characters in his movies, Lester had a zest for life that enabled him to live almost up to 100. Despite his advancing years, Lester kept up with the latest developments in the global movie industry and had a razor sharp memory. A Lake House photographer who went to meet him about a year ago told me how Lester inquired about his DSLR, asking for specifications one by one. I too had the rare privilege of chatting to him for about half an hour on the sidelines of a movie festival around 20 years ago and that was akin to a crash course in film studies. Such was the depth of his knowledge.

Many of his contemporaries in Asian, American and World Cinema have long since passed away. The 2012 documentar y The World of Peries, directed by K Bikram Singh, reveals Peries’s long-standing friendship with Indian director Satyajit Ray and with Indian film festivals. The two men admired each other but Lester had not seen any of Ray’s movies when he made Rekawa. Critics would later rave about the similarities in their cinematic narratives. Peries has cited Ray, Akira Kurosawa, Yasujiro Ozu and Adoor Gopalakrishnan as four Asian directors he admired the most. He was also a fan of Indian director Bimal Roy.

Admired

Lester’s name is also mentioned in the same breath as Federico Fellini, Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, Orson Welles (Lester admired Welles’ Citizen Kane based on the life of a newspaper magnate and even wanted to make a movie loosely based on the life of D.R. Wijewardene, the founder of this newspaper group), John Ford, Ingmar Bergman, Francois Truffaut, Jean Renoir, Vittorio De Sica, Michelangelo Antonioni and Roberto Rossellini.

The biggest tragedy that has befallen Lester’s movies is that some of them no longer have good quality negative prints as Sri Lanka still does not have an international standard, climate controlled film archive.

Thus we have lost some of his most seminal works to the ravages of time, nature and neglect. There are rumours that pristine prints of some movies are available in several foreign film archives, but so far no efforts seem to have been taken to trace them.

I recently had the rare opportunity of watching a fully restored copy of Nidhanaya (Treasure), perhaps Lester’s best known work globally, on the big screen. While the print had some smudges and marks that could have been erased with the availability of more funds and better technology, the quality was quite acceptable. Lamentably, none of Lester’s films has undergone a proper digital restoration by the likes of Criterion Collection, Kino, BFI, Twilight Time and other such exclusive labels. Criterion has done a stellar restoration of Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy about one year back which was released on Blu-Ray worldwide and there is no reason why a similar treatment cannot be given to Lester’s top movies which are also from the same era.

The authorities should at least now consider working with an art house movie distributor to get all his top movies released on Blu-Ray and DVD with multi-language subtitles and also to keep newly restored digital and film copies for posterity at a purpose-built world class film preservation centre. That is the ultimate tribute we can pay to Lester, the director par excellence who almost single handedly changed the course of Sinhala cinema. Such a new facility should, of course, be named after immortal Lester.