Although I frequent remote places in the interior of the country, it doesn’t mean that I dislike Colombo and its environs. It was in that spirit that I visited one of the busiest marketplaces in Colombo, Pettah - the biggest urban retail and wholesale market in Sri Lanka.

Although I frequent remote places in the interior of the country, it doesn’t mean that I dislike Colombo and its environs. It was in that spirit that I visited one of the busiest marketplaces in Colombo, Pettah - the biggest urban retail and wholesale market in Sri Lanka.

I am not a stranger to Pettah - after all, five days a week for more than 20 years, I used to walk along dusty streets of Pettah, where my office - Lake House - lies close to the Beira Lake. Pettah is a mosaic of human movement, architectural memories and heavy motor traffic complete with pedestrians. Lottery and other vendors scream and laborers known as Natamis sweat and toil with 50 Kg sacks on their backs, uttering an occasional slang.

‘Pitakotuwa’ in Sinhala means ‘outside the fort’. That is obviously how the Sinhala term for Pettah was coined to distinguish the area outside the Fort, which does not exist anymore. Pettah is an Anglo-Indian word from the Tamil ‘pettai’ introduced by the British to the area, which was identified by the Dutch as the ‘oudestad’ or old town.

Undoubtedly, the ‘oudestad’ was the nucleus in Colombo of the civic population in Dutch times. It had villas built off a grid of shady streets. One such “villa” was found in Prins Straat- since Anglicized to Prince Street in Pettah.

Even though there are more significant colonial Dutch buildings which were built by Dutch engineers between 1656 and 1796, in the crowded streets of the Fort and Pettah, I recently visited the most striking Dutch era building in Pettah, the Dutch period museum (1658-1796 AD).

The Dutch Period Museum nestles in the chaotic area of Pettah, housed in a building that is one of the country’s best examples of Dutch period architecture. It covers a span of almost 400 years.

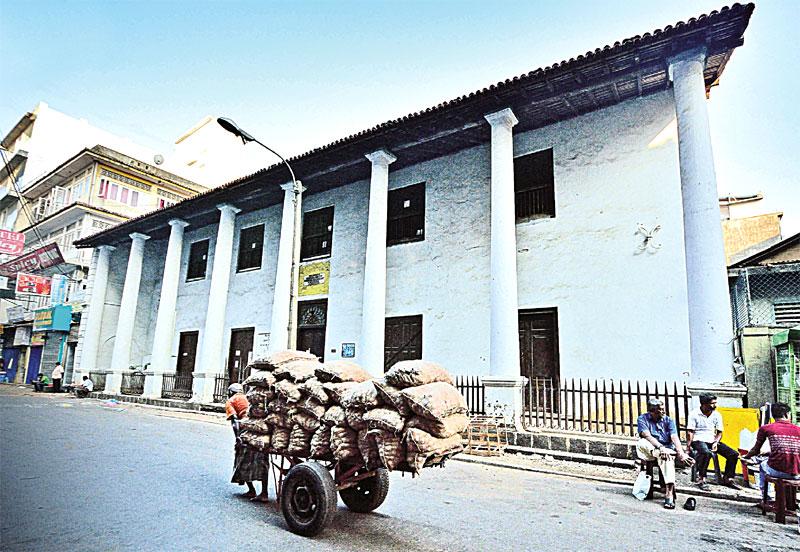

At seven o’clock in the morning, we hurried into the museum building to take photographs of the building’s exterior in a calm and quite setting before it gets chaotic with the bustle of street trading.

After a couple of hours we again walked south towards across Keyzer Street and into Prince Street. The bustle and urban din of the Pettah comes right up to the museum’s outer railings. Motorbikes, vans and carts are parked all along its street entrance. Shops selling plastic toys, cloth and hardware line the opposite side of the street.

With its tall white columns and flag-stone verandah, the building is an anachronistic but pleasant reminder of what was once a very chic and beautiful residential area for Dutch colonial officials. This building was the home of the Dutch Governor, Thomas van Rhee (1692-1697).

This fine house became the property of the Dutch East India Company before passing in 1776 to the British, who turned it into a military hospital. While all surrounding area was changing, the building survived, becoming variously an armory, a Police-training Centre, and finally the Pettah Post and Telegraph Office. It seemed doomed to decay until it was rescued in 1977 and restored to become a museum with the opening of Colombo’s Dutch Period Museum.

The Dutch descendant Deloraine Brohier was an active supporter of the museum and her father late R.L. Brohier revived the dream of a museum with some Burger lawyers. Brohier had plans drawn up to construct a traditional Dutch building to house such a museum. They and an active Dutch Burgher Union helped keep the idea and they deserved the credit for establishing this museum.

Actually, the Dutch Period Museum is a good place to ponder the Dutch legacy in Sri Lanka. The plan of the museum is a typical street house of the Dutch era; a two-storey, rectangular building flanked by two rows of solid white columns that support a modified tiled roof. Today, only the columns on the street façade reflect the scale of the building’s original grandeur.

Before entering the museum from the ornate doorway of the main entrance which is one of the few remaining of its kind left in Sri Lanka, we saw a Latin inscription over the lintel, set in a slab of rock that, reads (in translation) “Except the Lord build the House they labour in vain that build, 1780”. The main exhibits displays items for domestic use, intricately carved chairs, beds and tables that show off the best of what was known as Holland’s ‘Golden Age of Furniture’ , the late 16th and 17th centuries. Dutch officials brought a wide selection of furniture to make feel at home in Sri Lanka. They also brought master carpenters and craftsmen from Holland for their use. Within the short time, skillful copies of these furniture were made by Sinhala carpenters, using local woods such as calamander, nadun, satinwood and ebony.

Entering the ground floor, we came across two main exhibits which showcased the Dutch administration’s economic affairs, military affairs and religion and education. Most of the displays are copies of old manuscripts.

When we walked further inside through a narrow passage, we met a broad room containing old coins of the Dutch era. Huge wooden doorways with carved floral motifs are also displayed in this ground floor. An elaborate sword and sheath of a Muhandiram, the Sinhala noble title conferred by the Dutch to glorify the ruling elite are among the exhibits.

|

| The interior courtyard of the Dutch Period Museum. |

The walls of the narrow passage which leads to the courtyard from main entrance, display huge picture of Dutch emblems dedicated to each town in Sri Lanka. Next to this is a small bookshop that sells useful pamphlets and booklets on cultural heritage at reasonable rates.

After visiting the exhibits in ground floor, we stepped into the spacious verandah and courtyard of the Dutch Museum which is indeed, an oasis and a good place for a relaxing stroll. A lush green lawn, aged well, dotted with some trees in the courtyard is a tranquil space despite the clatter in the street outside. The little well set in the court was discovered when the grounds were excavated, lending a cloister-like serenity to the complex. The magnificent woodwork on the upper floor can be better appreciated from the back of the courtyard. Along the open verandahs flanking the quadrangle are old Dutch gravestones re-set in tile floors.

To reach the upper floor of the museum, two wooden staircases are located on both sides. We climbed one of the staircases. The upper floor is completely dedicated to Dutch furniture and several porcelain ceramics such as blue-and- white Chinese porcelain, VOC embedded ceramic plates and wooden and brass tobacco boxes, etc. Walking on the wooden floor, we came across more furniture incuding a striking carved Burgomaster chair in satinwood. These chairs with semi-circular or angular backs were in vogue among Dutch officials overseas.

Other well-preserved specimens include a satinwood settee and an elegant ebony couch. There are lovely chests made of nadun, an exquisite ebony crib and a stately almirah made of nadun. Next to the furniture display is an archival room with various maps, photo-copies of journals and pictures of Dutch period people.

The Sinhala- Dutch gallery of the museum also contains several displays of ancient artifacts belonging to the 17th century Kandyan Kingdom including the miniature MakaraThorana, some murals and Buddha statues. A detailed documents of Dutch judiciary system is also displayed prominently. The staffers of the museum are very helpful about giving details about the building and its exhibits as the museum is under the supervision of the Department of National Museums. The museum is open to public each days from 9.00 am to 4.30 pm except Sunday, Monday and public holidays. Colombo’s Dutch Period Museum is a fine example of architectural preservation, but it is more than that. The museum and the exhibits give testimony to the rich cultures of Netherlands and Sri Lanka that shaped today’s Sri Lanka.