The Bystander Effect is a social psychological theory which claims that a person is less likely to help someone in distress in the presence of other people. Psychologist John Darley conducted experiments with groups of people and noted that the percentage of people who reported the problem in the experiment was much higher when they were alone. When with other people, the percentage was nearly halved.

Map depicting the locations of concentration camps from 1933-1934 |

This experiment was carried out in different scenarios with different groups of people and the results were always similar. Darley’s interest in the Bystander effect was stirred up by the Kitty Genovese murder, more on that in a bit.

Origins

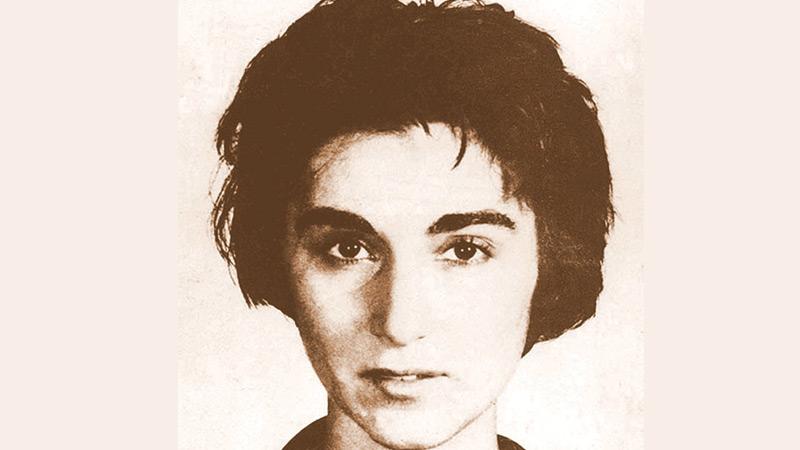

In 1964, a woman by the name of Kitty Genovese was murdered in a brutal stabbing. A short time later, the New York Times published an article headlined with “37 Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police.”

Abe Rosenthal, who was the head editor at the time, falsely claimed in the article that 37 people witnessed the murder and refused to help or call the authorities. Inconsistencies in the article were immediately identified but Abe wasn’t challenged as he was too powerful at the time.

Abe’s article went on to bring the Bystander Effect to light, which was a very real issue with society that definitely needed the mainstream attention. He was praised for his work and it even started to be taught in school psychology lessons.

However, decades later, it was revealed that only around 11 people had actually been present at the site of the murder and none of them had seen the whole ordeal.

In 2016, The New York Times admitted that no witnesses actually realized it was a murder and that two of them had notified the police with one person holding Kitty in their arms when she passed. For the most part, Kitty Genovese’s murder brought forth a very real problem in the form of a mostly fabricated newspaper article.

In 2016, The New York Times admitted that no witnesses actually realized it was a murder and that two of them had notified the police with one person holding Kitty in their arms when she passed. For the most part, Kitty Genovese’s murder brought forth a very real problem in the form of a mostly fabricated newspaper article.

In-group cohesiveness

Darley’s experiments and further studies conducted later on by other professionals also proved that walking together in a group of friends directly influences the way you act during a scenario as you tend to act differently when you are with people that you have established relationships with.

Darley managed to prove that when there’s a form of cohesiveness between people in a group, they become more likely to help the victim. The members of the group who had no bonds with each other took more time to help the victim and was noted as “less likely”.

Feelings of doubt

When ambiguity is high during a scenario, a person takes nearly 5 times as long to do something to help the victim. This is because people consider their own safety before stepping in. A high-stakes situation makes people less likely to step in due to fearing their own demise.

It was deduced by psychologists in 1969 that people tend to look at each other when something occurs so as to figure out what to do next. In most cases, a person will interpret another person not reacting as a sign that action from their end is not required.

I’ve witnessed this myself and it’s so jarring to see. During my pre-teens, I saw a man having a seizure on the sidewalk. My parents glanced at each other and after a subtle nod, they dragged me away. I didn’t think too much of it as a kid but looking back at it helped me understand how wrong they had been.

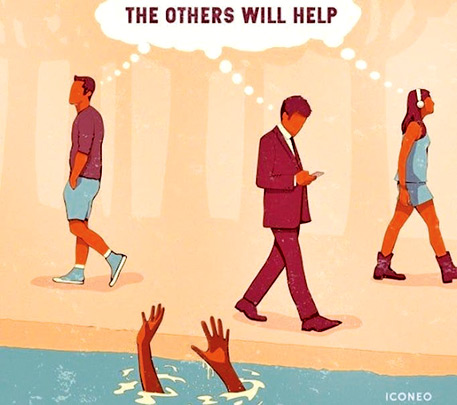

Diffusion of responsibility

The responsibility an individual feels varies depending on the number of people nearby. This can be clearly understood if you consider a group project. Let’s say five people are tasked with doing research on Global Warming.

The responsibility for the project is divided between the five members and the sense of urgency felt by each person is low. Moreover, the input from each individual in the group is also low compared to their input had they done the project alone. They depend and rely on the other four people to carry out most of the work.

This same theory applies to people in public scenarios. If a person is in distress and there is a large number of people nearby, a witness might not call for help or offer assistance because they will assume another person will do it.

This same theory applies to people in public scenarios. If a person is in distress and there is a large number of people nearby, a witness might not call for help or offer assistance because they will assume another person will do it.

Darley also conducted experiments regarding this and he clearly noticed that when a person is witnessing a situation alone, they have a higher sense of responsibility and they become more willing to step in and offer help.

However, there were experiments with anomalous results. This was because the test subjects witnessing the incident had personal relationships with the victim. John Dovidio, a psychologist at Yale proposed “we-ness”, which is the feeling that a person or multiple people are part of your group.

This “we-ness” exponentially reduces the chance of the Bystander Effect between friends and related individuals, but not strangers.

Historic examples

The biggest example that comes to mind is the Holocaust. Six million jews killed and not a single soul within a 20 mile radius stepped in to object. Villages such as Bergen-Beisen and Dachau had concentration camps close to them and the rotting smell of corpses would have been carried by the wind easily yet no one spoke out against it.

They simply ignored it and assumed someone else might do something about it.

The Allies during the war went on to severely punish the German population in these villages by having them bury all the corpses.

There are a multitude of other examples where lives could’ve been saved but the Bystander Effect kicked in. Be that as it may, the Holocaust really drives across simply how many lives can be lost.

How to reduce the Bystander Effect

Be the first one to take action. I’m not suggesting you rush in immediately with the intent of helping. I’m simply saying that you should calmly assess the situation and then take action.

If you’re the one seeking help, try to make eye-contact with someone nearby.

This brings about that feeling of “we-ness” I mentioned earlier and it will most likely prompt them to intervene.

Last but not least, ignore the consequences that might arise after helping somebody. Keep in mind that it’s a life you’re saving, although you should still prioritize your safety first.

The chances of the Bystander Effect occurring also reduces when people start to get more educated on the matter.

That was why I started writing this article so I hope I managed to convey the severity of this matter.