There are a few veterans on Hellenic studies in the world, but amongst them American Professor Edmund Keeley is foremost. He is not just an erudite scholar on the field, but a novelist, poet and translator which is a rare phenomenon. However, this great man of letters passed away on February 23 at his home in Princeton, New Jersey, at the age of 94.

Translating Greek poets

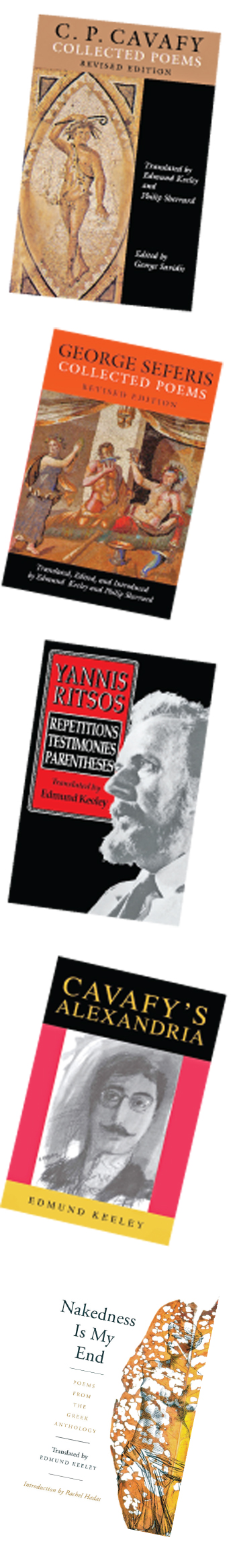

The greatest service he has ever rendered is to translating Greek modern literature into English. He brought an appreciation of modern Greek literature and culture to the English-speaking world. Especially, he is a pre-eminent translator of Greek poets like George Seferis and Odysseas Elytis, they both later won the Nobel Prize in Literature — a feat at least partly attributable to Professor Keeley.

He also translated a third poet, C.P. Cavafy who was born in Alexandria, Egypt. Cavafy is known for his mixed informal Greco-Egyptian idioms with formal high Greek, so translating him is a daunting challenge. However, Professor Keeley, rather than try to replicate the poet’s intricate flourishes, rendered the poems simply, retaining the power of Cavafy’s language even at the cost of some nuance.

His translation, with Philip Sherrard, of Cavafy’s poem ‘Ithaka’ was read at Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s funeral in 1994 as well. A portion of the poem, one of Onassis’s favourites, reads:

“Keep Ithaka always in your mind. Arriving there is what you’re destined for.

But don’t hurry the journey at all.

But don’t hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years, so you’re old by the time you reach the island, wealthy with all you’ve gained on the way, not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.”

He, not only, translated their work but also advocated for them in book reviews and journal articles in the U.S. and Europe.

A writer in his own right

Part of what made Professor Keeley such an effective translator was that he was a writer himself. He wrote novels, poetry and nonfiction, including travel, history and true crime books; his well-received ‘The Salonika Bay Murder: Cold War Politics and the Polk Affair’ (1989) proved that Greek authorities had framed a left-wing journalist for the 1948 murder of George Polk, an American radio reporter who was found floating in Thessaloniki’s Harbour.

Unlike many scholars of Greece, Professor Keeley was not a classicist; he taught in Princeton’s comparative literature department, and for many years he ran its creative writing program, recruiting boldface names like Joyce Carol Oates and Russell Banks to the faculty, according to The New York Times.

Later, he served as president of PEN America, which advocates for free expression in the United States and worldwide, from 1992 to 1994.

“He was the model of the man of letters,” Daniel Mendelsohn, a writer who has also translated Cavafy into English, has said in a phone interview to The New York Times.

His beginning

Edmund Leroy Keeley was born on February 5, 1928, in Damascus, Syria, where his father, James Keeley Jr., was serving as an American diplomat — a career that one of his brothers, Robert V. Keeley, would later follow. His mother, Mathilde (Vossler) Keeley, was a homemaker.

He led a peripatetic childhood, typical for the son of a diplomat, a few years in Canada, then Washington, followed in the late 1930s by Thessaloniki. He graduated from Princeton in 1949 with a degree in English literature and in 1952 received a doctorate in comparative literature from Oxford, where he studied with a fellowship from the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation.

In Oxford, he also met Mary Stathato-Kyris, a Greek graduate student whom he married in 1951. They lived together until her death in 2012.

Keeley’s interest in Greek literature was kindled when he lived in Greece as his father was the United States Consul in Thessaloniki. Greece was still considered a land lost in time, at least for many Americans, but he started translating modern Greek poets like George Seferis and Odysseas Elytis.

His fiction and non-fiction are often set in Greece, where he spent part of each year, but also in Europe and the Balkans, where he has frequently traveled, and in Thailand and Washington, D.C.

Teaching profession

In 1954, he joined as a lecturer in Princeton University and taught English, creative writing, and Hellenic studies worked. After 40 years of a long career, he retired from the University in 1994.

Keeley served twice as president of the Modern Greek Studies Association from 1970 to 1973 and 1980 to 1982, and as President of PEN American Centre from 1992 to 1994.

The facts reveal that from the beginning, he and his wife were at the heart of the campus social scene, organising parties and picnics for new hires, graduate students and visiting professors. The New York Times quoted Joyce Carol Oates’ views of him:

“Newcomers to Princeton were made to feel welcome amid a dazzling ensemble of writers, poets, professors, and friends from both Princeton and New York.”

Oates arrived in 1978 to the Princeton, intending to teach just one year, but thanks in part to Prof.Keeley’s generosity, she remained on the faculty even today. At the time, scholarship about Greece at Princeton was limited to the past and centered in the Classics Department.

Starting in the 1970s, Professor Keeley built what became the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies, now one of the leading institutions of its kind in the country.

Through the centre, he invited Greek artists and scholars to visit the United States and took scores of students on trips to Athens and its environs, standing at the front of the tour bus, microphone in hand, lecturing about his favorite Greek poets.

“It would be fair to say that for the last half-century he was America’s leading cultural ambassador to Greece,” Dimitri Gondicas, who now directs the centre, has said in a phone interview to The New York Times.

Clay Risen’s opinions

In his obituary report for The New York Times, Clay Risen said of Keeley as below:

“Through all his work, Prof.Keeley sought to change what the world thought of Greece. Following in the footsteps of philhellenic novelists like Henry Miller and Lawrence Durrell, and alongside his near-contemporary Patrick Leigh Fermor, the British travel writer, he revealed a country that was not just about gods and ruins but was in fact home to a thriving, creative culture.”

“Like Fermor, he gravitated towards Greek village life, the more remote and untouched by modernity the better.

In a richly informed style that reflected the many layers of history that constitute Greek society, he wrote in praise of those places where cars and cameras had not yet penetrated.”

Risen has reminded of a travel article by Prof. Keeley for The New York Times. There Keeley singled out Galaxidi, west of Athens, as “a village that has remained steadfastly out of date in style and untarnished by modern thinking ever since it decided that the steamship would never become a substitute for the clipper ships they built there to run Napoleon’s blockade.”

Life after retirement

After he retired from both Princeton and PEN America, he turned to writing full time.

He had already written several novels, and he went on to write several more — eight in all, most of them set in Greece and revolving around the theme of foreigners coming into contact with Greek culture.

He also took up poetry. Among his last works was “Daylight,” which appeared last year in The Hudson Review. A meditation on the Covid pandemic, it reads in part:

“Why not leave it all to Nemesis And take a long walk outside In whatever direction holds the prospect Of your recovering things to remember From those lighter years in open spaces That shore beside an endless sea.”

Some of his books are: ‘The Libation’ (1958), ‘The Gold-hatted Lover (1961), ‘The Imposter’ (1970), ‘Voyage to a Dark Island’ (1972), ‘Problems in rendering Modern Greek’ (1975), ‘Cavafy’s Alexandria: Study of a Myth in Progress’ (1976), ‘Ritsos in Parentheses’ (1979), ‘A Wilderness Called Peace’ (1985), ‘The Salonika Bay Murder, Cold War Politics and the Polk Affair’ (1989), ‘School for Pagan Lovers’ (1993), ‘Albanian Journal, the Road to Elbasan’ (1997), ‘On Translation: Reflections and Conversations’ (1998), ‘Inventing Paradise. The Greek Journey’ (1937-47) and ‘Some Wine for Remembrance’ (2002). He also wrote a memoir titled ‘Borderlines, A memoir’ published in 2005.

Awards

In his life time he has won 28 awards, some of which are: 1959 Rome Prize American Academy of Arts and Letters, 1959 Guggenheim Fellowship, New Jersey Authors Award for his three books (1960 for the novel ‘The Libation’, 1968 for ‘George Seferis: Collected Poems, 1970 for the novel ‘The Impostor’), 1962 Guinness Poetry Award selection, 1972 Guggenheim Fellowship, 1973 National Book Award in Translation (finalist), 1975 P.E.N. - Columbia University Translation Center Prize, 1980 Harold Morton Landon Translation Award, Academy of American Poets, 1982 Howard T. Behrman Award for Distinguished Achievement in the Humanities, 1983 PEN/National Endowment for the Arts Fiction Syndicate Award, 2000 PEN/Ralph Manheim Medal for Translation, 2010 Honorary Doctorate, University of Cyprus, and 2014 PEN Award for Poetry in Translation, for co-translator of ‘Diaries of Exile’ by Yannis Ritsos.

After demising of his wife Stathato-Kyris, Prof. Keeley met Anita Miller, his partner.

According to the Alan Miller, the son of Miller, the cause for Prof.Keeley’s death is complications of a blood clot. Anyway, the name of Edmund Keeley will remain in literary sphere as a writer who helped bring an appreciation of modern Greek literature and culture to the English-speaking world.