Nadine Gordimer is a South African author, who born on November 20, 1923 in Springs, Transvaal (now Gauteng), a mining town outside Johannesburg, and died on July 13, 2014 (aged 90) in Johannesburg. Though an author of few nonfiction works, she is a novelist and a short-story writer whose major themes are exile and alienation.

Gordimer’s father, Isidore Gordimer, was a Jewish jeweller originally from Latvia and mother, Nan Myers, was of British descent. From her early childhood, Gordimer witnessed how the White minority increasingly weakened the few rights of the Black majority.

Due to this she became a strong rival of apartheid - the official South African policy of racial segregation. Gordimer began writing at the age of nine, and when fifteen she published her first short story in the liberal Johannesburg magazine, ‘Forum’. Later, she spent a year at Witwatersrand University, Johannesburg without receiving a degree.

Due to this she became a strong rival of apartheid - the official South African policy of racial segregation. Gordimer began writing at the age of nine, and when fifteen she published her first short story in the liberal Johannesburg magazine, ‘Forum’. Later, she spent a year at Witwatersrand University, Johannesburg without receiving a degree.

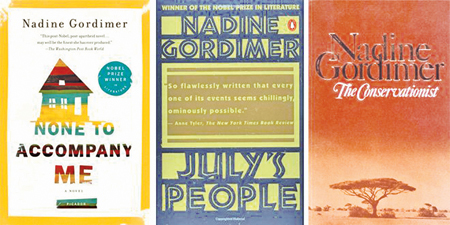

Her first book is ‘Face to Face’, a collection of short stories, published in 1949. The same year she married Gerald Gavron (Gavronsky), but soon divorced. In 1951, the New Yorker magazine published one of her short stories, and two years later her debut novel, ‘The Lying Days’ was published. In 1954, she married again, this time to a Jewish refugee, Reinhold Cassirer and together they have two children. Thereafter, her books appeared regularly, some of notable ones are ‘Burger’s Daughter’, ‘Get a Life’, ‘July’s People’ and ‘No Time like the Present’. In 1974 her novel ‘The Conservationist’ was a joint winner of the Booker Prize.

Gordimer was awarded 10 honorary doctorates in literature from various universities around the world. In 1991 she was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. In addition to writing, she lectured and taught at various schools in the United States during the 1960s and ’70s.

Nadine Gordimer’s art of fiction is revealed mainly from a Paris Review interview conducted by Jannika Hurwitt. Following are quotes from that interview which describes her writing method as well as tips for budding writers:

1. I work in the morning

Some writers should have a particular time to start writing. How about Gordimer’s time of starting point:

“I work in the morning. That’s best for me.”

2. I take at least 18 months

How long does it usually take her to write a book?

“It depends. The shortest has been about eighteen months. ‘Burger’s Daughter’ took me four years.”

Four years mean she had been writing the book for four years steadily? She says no, sometimes she had more than one program when writing:

“I wrote one or two other things, small things. Sometimes when I’m writing I get a block, and so I stop and write a short story, and that seems to set me going. Sometimes when I’m writing a book I get ideas for stories, and they’re just tucked away. But alas, as I get older, I get fewer ideas for short stories. I used to be teeming with them. And I’m sorry about that because I like short stories.”

3. Writer’s block

How does she overcome a writer’s block? She says starting a short story amidst novel writing, is a way of loosening her up.

“Yes, and occasionally I do some nonfiction pieces, usually something involving travel. For me, this is a kind of relaxation. During the time I was writing ‘Burger’s Daughter’ I did two such pieces.”

4. Noise

Conditions for writing are different from writer to writer. For instance, some writers are more obsessed with the environment around them, hence the need for certain necessities such as silence, special room, table and distance from people. How about Gordimer’s conditions?

“Well, nowhere very special, no great, splendid desk and cork-lined room. There have been times in my life, my God, when I was a young divorced woman with a small child living in a small apartment with thin walls when other people’s radios would drive me absolutely mad.

And that’s still the thing that bothers me tremendously — that kind of noise. I don’t mind people’s voices. But Muzak or the constant clack-clack of a radio or television coming through the door... well, I live in a suburban house where I have a small room where I work. I have a door with direct access to the garden — a great luxury for me — so that I can get in and out without anybody bothering me or knowing where I am. Before I begin to work I pull out the phone and it stays out until I’m ready to plug it in again.”

And that’s still the thing that bothers me tremendously — that kind of noise. I don’t mind people’s voices. But Muzak or the constant clack-clack of a radio or television coming through the door... well, I live in a suburban house where I have a small room where I work. I have a door with direct access to the garden — a great luxury for me — so that I can get in and out without anybody bothering me or knowing where I am. Before I begin to work I pull out the phone and it stays out until I’m ready to plug it in again.”

5. Solitude

How long does she usually work every day? Or does she work every day?

“When I’m working on a book I work every day. I work about four hours non-stop, and then I’ll be very tired and nothing comes anymore, and then I will do other things. I can’t understand writers who feel they shouldn’t have to do any of the ordinary things of life, because I think that this is necessary; one has got to keep in touch with that.

“The solitude of writing is also quite frightening. It’s quite close sometimes to madness, one just disappears for a day and loses touch.

“The ordinary action of taking a dress down to the dry cleaner’s or spraying some plants infected with aphids is a very sane and good thing to do. It brings one back, so to speak. It also brings the world back.

“I have formed the habit, over the last two books I’ve written, of spending half an hour or so reading over what I’d written during the day just before I go to bed at night. Then, of course, you get tempted to fix it up, fuss with it, at night. But I find that’s good. But if I’ve been with friends or gone out somewhere, then I won’t do that. The fact is that I lead a rather solitary life when I’m writing.”

6. Three times

Revision is an essential part in writing fiction. How about Gordimer’s revision?

“As time went by, (revision became) less and less than I used to. When I was young, I used to write three times as much as the work one finally reads. If I wrote a story, it would be three times the final length of that story. But that was in the very early times of my writing. Short stories are a wonderful discipline against overwriting. You get so used to cutting out what is extraneous.”

7. Critics

Are critics useful for Gordimer?

“Yes, but you must remember they’re always after the event, aren’t they? Because then the work is already done. And the time you find you agree with them is when they come to the same conclusions you do. In other words, if a critic objects to something that I know by my lights is right, that I did the best I could, and that it’s well done, I’m not affected by the fact that somebody didn’t like it.

“But if I have doubts about a character or something that I’ve done, and these doubts are confirmed by a critic, then I feel my doubts confirmed and I’m glad to respect that critic’s objections.”