“[Hegel said] ‘The spiritual result of the Peloponnesian War is that Thucydides wrote the book on the Peloponnesian War.’ I like this crazy idealist notion that things in reality happen so that then a book can be written about them”

– Slavoj Žižek

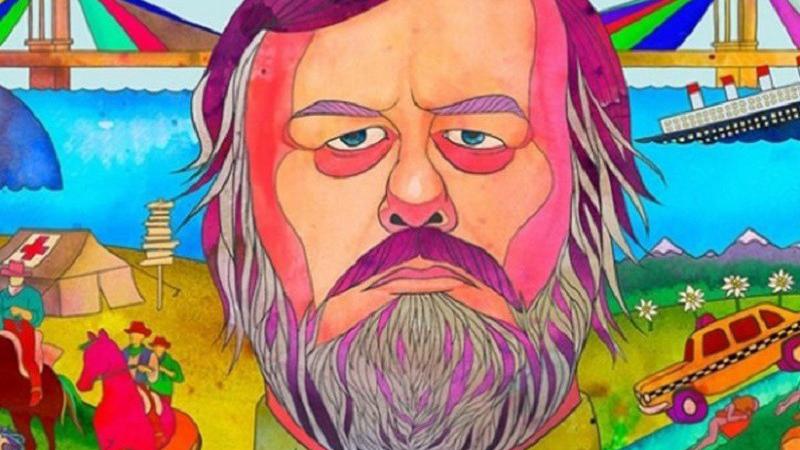

Is it any surprise that in this day an age one of the most high profile academic and public intellectuals is also one of the most controversial? Slavoj Žižek is a Slovenian continental philosopher, a political and cultural theorist, a returning faculty member of the European Graduate School, and the founder and president of the Society for Theoretical Psychoanalysis, Ljubljana. He is a Marxist and a Hegelian, famous for his eccentric sense of humor and bold, frequently controversial, dialectical reversals. His politics and perspectives have gained him a great deal of attention over the last few years. More recently Žižek claimed he would have voted for Trump in order to save the left (Sanders would have been his pick) and argued the presidential election in France was not much of a choice at all. The neoliberalism of Macron would eventually give rise to neofascism of Le Pen anyway.

Žižek’s cultural critique can often be found through his film criticism. He was exposed to the films, popular culture and theory of the noncommunist West as he grew up in the socialist former Yugoslavia. Žižek helped create five documentaries, his most recent and most notable being the The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema (2006), and The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology (2012). Within these two films Žižek analyzed key scenes from over 60 movies made between 1931–2008.

Slavoj Žižek is brilliant and idiosyncratic. He rubs many the wrong way with his provocateur nature and consistent deviation from normative values. Žižek is a big proponent of ideology even as the term has grown out of fashion. He believes, again controversially, that we do not in fact live in a post-ideological or post-political world. He does not always play well with other academic intellectuals; Noam Chomsky is not a fan mostly because he see’s little to gain from the intangible theories of continental philosophers. However, it would be a great disservice to Žižek to simply think of him as an entertaining agitator or a dyed in the wool devil’s advocate. Instead of focusing on who or what a public intellectual is we should be more concerned with the work public intellectuals must do. Žižek is not ambiguous about his intentions, he has often said his work has very serious philosophical content and intention. Despite a seemingly increasing political presence, Žižek himself laid out the true thrust behind his work.

“What I really want to do is rehabilitate classical philosophy today… I am even more for Hegel than I am for Marx. I think we should return from Marx back to Hegel so this is the focus of my work. Then come all the things for which I am unfortunately better known. For example, my dealings with critique of capitalism, analysis of popular culture and so on and so on. But frankly, all these, my writings on politics and analysis of Hollywood… are more or less collateral damage of my basic work.”

Thucydides’ History and the Value of Cultural Consolidation

Returning to the Hegel quote which Žižek regards fondly, “The spiritual result of the Peloponnesian War is that Thucydides wrote the book on the Peloponnesian War.” The way Žižek interprets this idea is as an ontological question about how and why things in reality happen. What Hegel alludes to is the notion that story makes up our history as much as facts do. The facts of a historical event are littered all over the place and supportive to one or more of any countless different potential narratives. The artist, just as the historian, takes these facts, picks and chooses what is deemed significant and strings a few together to create narrative. This narrative serves to consolidate the meaning of the time and place of that historical event. This is not always a frictionless process; often multiple narratives are generated from the same facts. This leads to historical debate, a competition between two or more narratives. As one gains favor over the others through support, elimination, or authority it becomes the dominant narrative. There may be multiple truths but one tends to become the truth. Human history is a series of cultural consolidations.

Hegel valued these consolidations and recognizes the multiplicity inherent in their creation, just as Žižek does. In this way there are many lenses through which we can see the past, beyond that which has become dominant. One of Hegel’s guiding beliefs was that we can find and salvage important lessons from the past. Every era provides some reservoir of a specific kind of wisdom. Society’s progress, by nature, is not linear. It is nice to think we are perpetually improving but truthfully what is deemed “good” and culturally relevant fluctuates with society. As we move forward in time, gaining new knowledge, we inevitably lose things of value. For example, if we identify our driving need for individualism today has made us lose sight of the importance of community we can look to the values of community practiced in Ancient Greece for answers. There has never been a perfect civilization. There are many ugly truths tied to every period. But Hegel believed we can use cultural consolidation as earmarks or timecapsoles, aiding our search for the good in the past. We have the advantage of history to learn from the mistakes of the past and repurpose wisdom to apply for ourselves.

Cinema as Cultural Consolidation and the Tension Between Form and Content

“[I] use cinema as a tool to analyze our ideological predicament. It’s nice but it’s not yet an imminent analysis. Imagine there is no movie but just the basic story of the movie, the whole analysis stands so it’s not really about the movie…”

This is where I have to disagree with Žižek and will use his own work as support. The most important point that I want to make here is that the basic story of a movie becomes significantly weaker if it is not actually a movie. In other words it is narrative content without it’s form. I will share several passages of imminent analysis from Žižek on the medium of film and its form as justification for his work in film criticism. What is cinema if not a kind of cultural consolidation? Thucydides was a historian who consolidated history as story in the form of a book. Artists preserved history in other forms. This widened the accessibility of knowledge, allowing engagement through different mediums. The written word, picture, music, sculpture, theater, all became pieces of the narrative. Film is a natural convergence point, a place where many different forms of art collide and merge. Just like a book, film creates a story as a sensuous exhibition of ideas. Film weaves narrative from pure facts and figures that would leave us cold. But unlike a book’s written word, film leans on other aspects to tell a story. An unproduced script, without the cinematography, performances, editing, score, etc. is incomplete. There are many artists behind every layer on a film’s canvas. If each does their job well then they all contribute to the eventual final product. If we are to hold up the script in comparison to Thucydides book it will be a hard comparison. A good script certainly holds up on it’s own as a piece of narrative, but it alone does not make a movie.

How Hitchcock Makes Film Think

“Film is thinking where the form has its own dynamic which does not simply illustrate the narrative content but tells more”

What does this look like in film? Žižek references several ways this is done effectively. Lars von Trier’s Meloncholia is a very unorthodox romance film. It manages to subvert many preconceived expectations of the genre because of a very interesting tension between it’s narrative content and form. Žižek notes how the movie is filmed almost like a documentary with a lot of disjointed, rough cuts and liberal use of hand held camera shots. A genre known for clichés, story book endings, and sappy romanticism is rendered tangible and authentic. Von Trier himself said without this tension created by the form the narrative would be unbearable. Because there is conflict within the very fiber of the film another layer of drama is created beyond that which appeared on the page.

More examples can be found in Žižek’s, The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema and The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology documentaries. For clarification the title to his two most recent projects, The Pervert’s Guide…, is a reference to one of the focal tenants of Žižek’s cinema philosophy. Žižek claims there is nothing spontaneous or natural about our desires, they are artificial constructs, something we must be taught. He calls cinema the ultimate pervert art because it doesn’t merely give the audience what they desire but instead teaches the audience how to desire. This sounds remarkably similar to how he speaks about philosophy, a tool that “…teaches us what we have to know without knowing it, in order to function.” In, The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema, Žižek references a scene from Hitchcock’s The Birds. After witnessing chaos on the streets, Hitchcock cuts to an extreme wide shot way above the small town scrambling in disarray. The audience immediately registers this shot as a standard establishing shot of the pandemonium unfolding on the ground. These shots are important to reorient the viewers from the micro level of fast passed action to a macro perspective of the bigger picture. But then something changes. The ominous sounds of the birds slowly become distinguishable as one bird appears, than a few, than a whole flock overwhelms the screen.

“I am always fascinated by movies where there is a subtle tension between narrative content and the form. Form does not simply illustrate the narrative content but counteracts it, even subverts it.”

Film Can Be More Than A Snapshot in Time

On film’s practical role, Žižek maintains his high aspirations. As Hegel said, Thucydides’ account of history is just as important as the pure facts. Once it is in the form of a story new meaning can be ascertained even beyond the societally agreed upon dominant narrative. Žižek references a story about the director of the film The Fast Runner. The movie stages an old Inuit legend and changes the ending from it’s original tragedy to a softer more ambiguous close. In this instance, the director was reproached for “succumbing to Hollywood commercialization” in that, he was not faithful to the original story. The Inuit director responded by saying this is a misguided white perspective of his movie. Retelling the story in different ways to fit the present circumstances is the Inuit tradition. A notion of always being faithful to the original is a classically western ideology. Žižek appreciates this story and Hegel’s perspective of Thucydides because he views film as a medium that can surpass looking at the reality as a rendering or mere reflection of a culture. A film isn’t a narrow or shallow snap shot in time, it’s a story that transforms and melds different aspects of the existing society. It does not have to be regarded as pure fact, but a cultural consolidation. This is film’s creative and generative power beyond a localized view.

Today film stands as one of our most powerful story institutions, exactly what Hegel sought. He believed institutions allowed for the scale, reach, and cultural significance required to make big stories about our society effective in the world. These stories are about our relationships, dreams, fears, and lives. Sometimes they are reflected in the popular art in which ideas stand in sharp relief as an easy reference point. Sometimes they are reflected in subtler ways, as Žižek says, true art shows things directly but in such a way that you are aware that what you see is not really the thing that we are aiming at. Movies create cultural consolidation which can tell us stories about facts and more importantly about our perception of our own history. Žižek should be proud of his efforts to elucidate lessons from our film history and assured in the knowledge that this work is much more than mere “collateral damage” to his efforts to rehabilitate classical Hegel philosophy. It is obvious he appreciates cinema by the eloquent way in which he speaks of it. I will end with a final quote from Žižek on the film Possessed made in 1931. In a very meta way this movie scene gives a commentary on the magic art of cinema. As an ordinary girl approaches a train station she see’s the windows of every passenger car slowly chugging by. Each shows an intimate vignette of a life beyond her own.

“We get a very real, ordinary scene on to which the heroine’s inner fantasy space is projected. So that although all reality is simply there, part of reality, in her perception and in our viewer’s perception is, as it were, elevated to the magic level. It becomes the screen of her dreams, this is cinematic art at it’s purest”