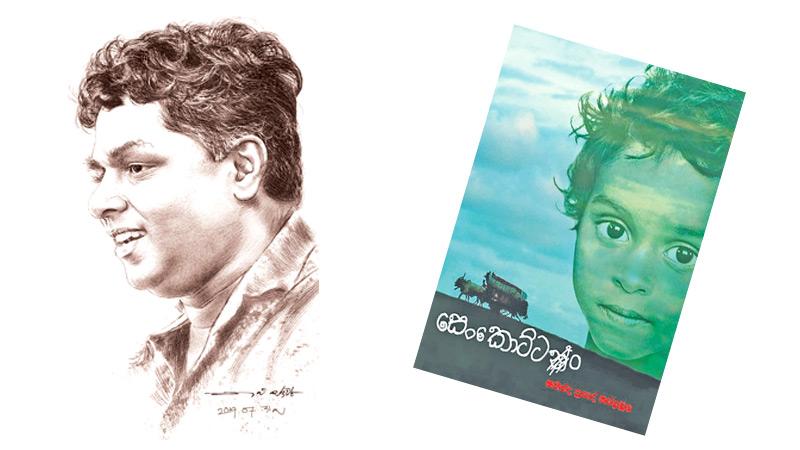

Making a sincere attempt to bring an unimagined and unexplored treasure trove of modern Sinhala literature to the English reading community, from this week onwards, Montage is bringing Mahinda Prasad Masimbula’s award winning novel ‘Senkottan’ translated by Malinda Seneviratne, veteran journalist, writer and poet.

‘Senkottan’ (The Indelible), a remarkable creation of literature by Mahinda Prasad Masimbula was his debut effort in his literary career for which he won the State Literary Award in 2013 and short-listed in Swarna Pusthaka Literary Awards and many other Literary Award Festivals in the same year. The book has been published by Santhawa Publishers and ‘Senkottan’ has blazed the trail in the self-publishing industry as one of the best-selling books in Sinhala literature.

‘Taaang……taaang….taaang…’

The sound came from a fairly large cart one afternoon in the nineteen thirties. Having started its journey in Embilipitiya and making its way towards Ratnapura it was at this time passing Pallebedda. It was half stacked with copper ware, large and small. The Buddhist flag hung at the front was fluttering in the dry wind. The time would have been around two o’clock. The harshness of climate seemed to relent as they moved from Embilipitiya through Kolambageara, Udawalawa and Pallebedda. The pair of bullocks appeared to be united in thought and intent as they ambled along. In the cloudless sky there was but a single hawk racing a large circle. The carter seemed to be deep in meditation. If his trance was interrupted it was only when he drew on the cigar hanging at the corner of his mouth as though with all his strength. After a while, as if he had suddenly remembered that he was a carter, he would prod the beasts gently with his foot and mutter ‘juh!’ a couple of times. The bullocks continued unperturbed. The road was clear except for the occasional cart or two that would pass in the opposite direction. One man walked parallel to the cart while another sat at the back. They both wore white sarongs and white vests. It was the older of the two, elderly in appearance, who went on foot with his head wrapped in a cloth. They were both in appearance upasakas; devotees, steadfast in faith, on a pilgrimage, it seemed. The man at the back of the cart bangs on something like a small shield with an iron rod.

‘Taaang……taaang….taaang…’

The carter, his cigar held firm at the corner of the mouth and gazing on the road ahead, spoke.

‘It’s no use upasaka mahattaya…there aren’t too many houses in this area. Godakawela will be where we will first encounter a row of shops. We will get there when the sun is about twenty yards above that mountain.’ The carter makes such pronouncements on time having made calculations related to the sun during a journey to Embilipitiya along this same road a few days previously. The sun was at its zenith. The principal upasaka, figured that it would take two to three hours more for the sun to reach the point indicated. Upon hearing the bellowing of a cow from a distant paddy field, the black bull desired to stop and investigate, but the brown bull, on the right was not interested. In the evening of life, all it wanted was to be at peace. Sensing this, the black bull held its disappointment and proceeded as before.

The younger upasaka who was falling asleep was suddenly awoken when the cartwheel went over a stone. He looked around.

‘We have passed even Pallebedda,’ he told himself as he got off the cart and hurried towards the older upasaka.

‘Upasaka mahattaya….why don’t you go sit at the back?’

Accepting the invitation, the older upasaka swung himself into the back of the cart. He handed the piece of bronze and the iron rod to his companion.

The hawk seemed to be flying at an even higher elevation. They passed a few more houses close to Balavinna. The moment they came into view, the younger upasaka beat his bronze shield with the iron rod. The carter knowing that there was no reason to stop, kept moving. A few naked boys and girls playing in the compounds of their homes rushed to the fences and watched them.

‘The adult folk have gone to the paddy fields, it’s just the kids who are at home,’ the carter muttered, just loud enough for the younger upasaka to hear. The older upasaka was by this time fast asleep.

‘Anyway, there’s a good collection of bronze already. There’s still a long way to go to Anuradhapura. The collection will grow handsomely as we go along….’

The carter chuckled to himself. He felt proud that he too was contributing to this noble task. He drew on his cigar once more, this time with a sense of self-importance.

Even the younger upasaka felt they had indeed collected quite a lot of bronze. The cart stopped only where there were shops. When they did, the villagers, having listened to what the older upasaka said gifted as much bronze as they could, their hearts filled with the joy of being somehow associated with the Buddha. He was amazed by the faith of these people. Passing Balavinna they came across a cart parked under a kumbuk tree and close to a stream. The carter was playing a bamboo flute. It was a cart that transported bananas from Galpaya to the Godakawela weekly fair.

The bull, feeding on the tender leaves of grass, stopped a moment upon sensing the presence of the bulls of the bronze cart and then returned to its meal. An idea came to the carter of the bronze cart.

‘Podi upasaka mahattayo, the animals are exhausted….shall we look for a shady spot and stop for a while?’ ‘If we stop now we won’t be able to reach the Gallengoda Temple before dark. That’s where we are to spend the night. We have to stop at Godakawela for an hour or more anyway, so let’s keep going.’

‘It doesn’t make a difference to me. All I have to do is to sit on the bar and pull on my cigar…I was only worried about these beasts.’ Since the young upasaka did not respond, the discussion ended there. An hour later they reached Godakawela. There weren’t more than five or six shops. Peter, who made hoppers had a tea boutique.

There was a foundry and a couple of retail shops. By the foundry was the shop where Wine Mahattaya, the tailor, had his sewing machine. A little further away, under a Mara tree, was a place to tie the bulls. Since the Dombakodella river flowed by the row of shops, the carter made straight for the water after untying the animals.

The older upasaka, as though to draw the attention of the people gathered at this township, untied his head wrap, tossed it over a shoulder and in a loud but friendly voice said, ‘let’s first have a chew of betel…..’ and proceeded to do just that.