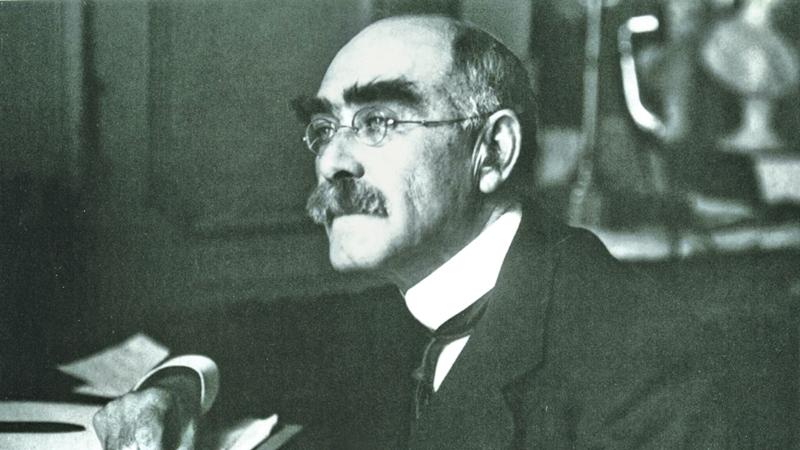

The celebrated British author Rudyard Kipling one day received a parcel simply addressed, “To Monsieur Kipling.” When he unwrapped it, Kipling found a French translation of his novel Kim. Surprisingly, the book had a bullet hole through which the Maltese cross of the Croix de Guerre, France’s medal for bravery in war had been tied with a string.

On further examination, Kipling found that the parcel had been sent by a young French soldier, Maurice Hamonneau. His note said, “If not for the ‘Kim’ in my pocket, I would have been killed in the battle.” The young man had requested Kipling to accept the book and the medal as a token of gratitude.

The Kiplings had two daughters, Josephine and Elsie. His only son John was a bright, cheerful and an uncomplaining child. His six-year-old daughter Josephine contracted pneumonia and met with an untimely death. Kipling showered his love on Elsie and John. Meanwhile, Kipling collected his fantastic tales about wildlife and published a book titled, Just So Stories in 1902.

Education

Kipling was born in India in 1865. When he turned six, he and his younger sister Trix were shipped off to England for their education. The woman who was employed to look after the children ill-treated Kipling. Sometimes, he was locked up in a cold, damp cellar for hours. Despite such ill-treatment, Kipling remained cheerful. The tremendous suffering he underwent made him treat his own children with extra love and care.

Back in India, Kipling worked as a journalist. During his spare time he wrote fiction. His stories depicted courage, sacrifice and discipline, the hallmark of the British army. However, newspaper editors in India did not treat Kipling kindly. Ignoring their discouraging remarks, Kipling continued to write fiction. When his books became popular, academics and politicians sought his services.

While Kipling was involved in journalism and fiction writing, his son John was growing up to be a handsome youth. John loved sports and Kipling used to watch him play rugby. Unlike most sportsmen of the day, John congratulated his team mates and even his opponents on their skills. He never boasted about his victories or brooded over his failures. Kipling was happy to see his son turning into a responsible man. So he encouraged him to achieve his ambitions in life.

Literary critics

In 1910 Kipling started writing his celebrated poem If always thinking of his 12-year-old son. He included the poem in one of his collections. Literary critics, however, did not see anything great in the poem. For them it was just another poem. Quite unexpectedly, the poem became highly popular among readers in a matter of a few years. Up to now the poem has been translated into 27 languages. A few decades ago, we had to learn the poem by heart. The printed version of the poem was available in certain bookshops. Most of the students had the poem framed and hung in their study rooms. In England, young soldiers marched off to battle reciting the poem. Today, If remains an inspirational poem in most countries.

While Kipling was flourishing as a writer, John joined the Irish Guard as a Second Lieutenant as his application to join the British army and navy was rejected because of his poor eyesight. While John was serving in Ireland Kipling was in France writing war reports. Britain was losing the battle and some of the recruits went overseas. At 17 John had a choice. He needed parental consent to serve in the battle front. As fate had decreed, Kipling gave his consent.

Just after six weeks, a messenger arrived at the Kipling estate bringing a telegram from the War Office. “John is missing in action,” the message said. Kipling was left feeling totally devastated. He started visiting hospitals looking for his son thinking that he might be somewhere as a wounded soldier. However, he received no news about his son even after a few months’ search.

Eye-witness

Towards the end of 1917, Kipling met an eye-witness who claimed to have seen John dying in the Battle of Loos. However, John’s body was never found. After the war, Kipling worked as a member of the Imperial War Graves Commission which was tasked with reburying and honouring the dead soldiers. Kipling always remembered that he had sacrificed his greatest gift – his son – to the war.

The poem If is reproduced here for the inspiration of readers.

-----------------

If

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you;

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or, being hated, don’t give way to hating,

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise:

If you can dream – and not make dreams your master;

If you can think – and not make thoughts your aim,

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two imposters just the same;

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken

Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools,

Or watch the things you gave your life to, broken,

And stoop and build ‘em up with worn-out tools:

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss;

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: “Hold on!”

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with Kings – nor lose the common touch,

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you,

If all men count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And – which is more – you’ll be a Man, my son!