Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, the champion of nationalism in this country, wanted to change the prevalent political landscape with his back-to-land Sangha (Bhikhus), Veda (Physicians), Guru (Teachers), Govi (Farmers), Kamkaru (Working Class) policies. Bandaranaike was shot and killed, of course for unrelated reasons, and history may or may not have been different had he lived to accomplish his larger mission.

There are those who would swear that Bandaranaike did what he did for political advantage, and none other than his daughter Sunethra Bandaranaike seems to have suggested the same in a recent interview. But the question is probably not so much whether Bandaranaike was sincere or not. He may have been a convert to the nationalist cause. He may have convinced himself, even, against his previous better judgment, that it is essential to carry out reforms particularly in the area of national language policy.

But the more relevant question, 67 years after he swept to power in the nationalist revolution of 1956, is whether the helmsman of nationalist-transformation organically related to the causes he espoused? If he did not, then would he be able to represent that cause, and inspire change, just because he changed his garb, became a devout Buddhist, and acquired some trappings?

Probably a very few historians would venture to say that he was a man who, being to the manor born, was able to transcend his innate characteristics — i.e., those of a ‘gentleman’ in the tradition that the colonial power left behind. It is not the external drama of course, but the internal confusion that matters. He donned the suit on occasion and once when asked why he wore a bow and tailcoat for a dog show, is said to have replied with a smirk, balu wedeta balu enduma. (Cur-garb for canine pursuits.)

The fact that he was comfortable with the English-speaking elite and hobnobbed with the lot when he was invited for society soirées does not necessarily mean he was no nationalist. He did not want to jump out of his skin entirely; that was not necessary anyway, because it was the cause that mattered and not the individual chosen to lead the movement.

INDOMITABLE

But was it quite like that? If Bandaranaike was not an organic nationalist, should not he have cast aside the trappings and become someone more comfortable in his own skin? Is that like saying Simon Bolivar should have retired and done some gardening at home?

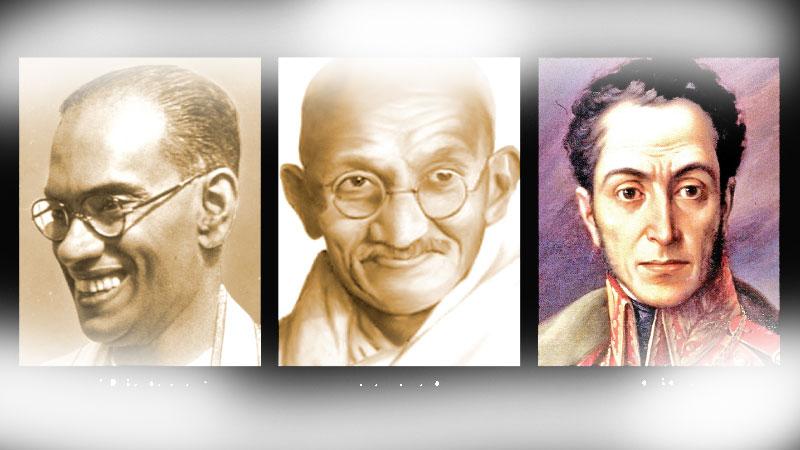

For the uninitiated, Simon Jose Antonio Bolivar, of aristocratic Spanish-American lineage, is considered the Liberator of South America. Most of Northern South America including Bolivia (which is named after him), Columbia, Venezuela and so on owe their independence from Spanish colonial rule, to Bolivar. But Bolivar though the liberator of his people was of aristocratic descent and was enamored with European institutions and for instance, having convinced the British to assist in his quest for liberation of South America from the Spanish, wanted European style Parliaments in Colombia and the nations he liberated.

He wrote poetry in Spanish and is admired — nay deified — in South America to this day, as a man of a great combination of talents, a prophetic vision and an indomitable temperament.

Liberator of South America, he was organically a man close to the aspirations of the people of that continent. He fought with the men if not in the trenches, in the vast and dangerous theatres of combat. To this day there is a Bolivarian party in South America and young people go along the streets yelling his name, which they do not in the US (i.e there is no party for George Washington, and no political idolisation of the founder.) Despite his aristocratic past, and his obvious political preferences for Westminster style democracy with some modifications, Bolivar was organically a South American rebel who led his people to war and eventually liberated entire countries — Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, and the list goes on.

Bandaranaike — even the comparison is fairly fraught — was a leader cut from a different cloth. He had no such tangible organic connections with the people, or the people who gave life to the causes that he espoused. It is why very often one finds history judging him as not merely an agent for change but also an opportunist.

Nobody dares say for instance that Simon Bolivar was an opportunist. That is not just because he fought and won armed rebellions. It is also because he was organically immersed in his cause, and was willing to make tremendous personal sacrifices to achieve them.

Those who are not organically close to the people or their causes should not probably attempt to make transformative change because they cannot steer causes — even nationalist causes — towards a fitting finale, even though of course people would say that doesn’t apply to Bandaranaike because he was assassinated before he could accomplish his mission. But Gandhi was also assassinated before he could accomplish his most cherished goals, but yet had already established a trajectory for his nation that was so clear, it endured for decades to come.

Those who were not organically close to the people or their causes generally did not pretend to be ardent. Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kwan Yew was an Anglophile technocrat and knew it to be his limitation. It does not appear that he considered anything a fetter, however, in accomplishing what he considered a very pragmatic goal. There was no ardent nationalism there. He just seems to have wanted to get things done, and did.

Those who are not organically immersed in their causes can be imperious and autocratic as Lee was, but they still earn the respect of the people as pragmatists. But, those who give leadership to causes that they themselves have to convert to, have a hard time giving leadership. That is why nationalism in Britain, for instance, probably is such a colossal failure today. The Conservatives who gave leadership to Brexit are not even close to being organically related to the causes of the people they purport to represent.

ELEMENTAL

What are those causes? Economic uplift would surely have been one of them, but ordinary folk did not call for anti-immigrant policies, it is just the demagogues and the petty demagogues on the streets that did. When past British Prime Ministers did what they could do, which is to go about clinically improving market conditions and affecting a fair amount of deregulation, they did well, but the moment they began breathing fire espousing causes they did not organically relate to, such as so-called populist causes meant to keep Britain British, they ended up messing things up dramatically.

Bandaranaike’s cause was stillborn. They did not build shrines to him as they did to Bolivar, or Gandhi. There are Bolivar Squares in multiple countries in South America and each one is different. There is a Gandhi Street in almost every Indian town.

Why for these larger than life icons, and not Bandaranaike? One reason may be that Bandaranaike skirted above the hurly-burly. The second may have been that for a fairly polyglot nation such as ours his language reforms and so were not quite what the hour called for, especially in the way those so-called reforms were enacted.

Leaders of a later vintage, did not make any revolutionary promises and got about their business pragmatically with the minimum of nationalist trappings. It’s probably because those including J.R. Jayewardene knew that they had little or no organic relationship with the people. They were for the people, but they were not of the people, period.

JR’s Dharmishta and so on were more slogans and appendages, than real battle cries, and this is probably why he did not set himself up as an agent for revolution. He wanted incremental change, and in his own way achieved a good deal of what he set out to accomplish, even though the legacy of the institution of the Presidency for instance came to be much maligned.

But what can be said definitively is that he knew he had to work within his limitation, which is that he had no organic relationship with the masses in the elemental sense that Mohandhas (Mahathma) Gandhi had with his.

Of course Gandhi was an English educated lawyer, and was no rural yokel either. But yet, he walked the walk, and didn’t merely talk the talk. The people knew instantly that this was a visionary, and Bolivars and Gandhis only appear like the comets — very rarely, yet so spectacularly, it is a sight to behold.