“Two-hundred-and-eight elephants killed in Anuradhapura in two and a half years”, “One elephant a day: Sri Lanka wildlife conflict deepens as death toll rises”, “One dead after wild elephant attacks camper couple”. In Sri Lanka, headlines like these are not rare; the Human-Elephant Conflict (HEC) has become routine – claiming lives and devastating the economy at the same time. Unlike in Africa, elephants in Sri Lanka are not killed for their ivory, but HEC is a direct result of encroachment into elephant habitats.

The primary cause of HEC in Sri Lanka is the competition for resources, particularly land and water. The other key factors leading to HEC include habitat loss and fragmentation due to deforestation and encroachment into elephant habitats, elephants raiding agricultural areas for food causing crop damage and economic losses for farmers, human population growth, urbanisation and infrastructure development leading to habitat encroachment and disruption of elephant migratory routes and lack of natural corridors for elephants due to the development of roads, railways and fences.

Elephant drives

For decades, the country had used two methods to tackle the problem; elephant drives and electric fencing, with little success. Elephant drives, which involve chasing elephants out of specific areas are a legacy of colonial times when the British conducted ‘game drives’ to chase wildlife towards a sportman’s gun. Drives were also used to chase elephants into keddahs which are stockades constructed for capturing elephants.

However, a report published by the Centre of Conservation and Research (CCR) in 2020 titled “Elephant Drives in Sri Lanka” discusses the practice of elephant drives in the country and their impact on HEC and elephant populations.

The report highlights that large-scale drives aim to eliminate elephants from extensive landscapes, while medium-scale and small-scale drives target specific areas or incidents.

The report states that the effectiveness of elephant drives in reducing HEC and removing problem-causing elephants is limited. Problem-causing adult males, responsible for most conflicts and crop raiding incidents, are difficult to remove through drives, leaving them in the drive areas. The elephants that are driven out and confined in protected areas are often the females and young, causing little conflict. However, some herds and problem-causing elephants remain in the drive areas. The report suggests that drives have resulted in increased aggression among elephants, escalating conflicts in the drive areas.

Monitoring of GPS-collared elephants subject to drives confirms that problem-causing males cannot be effectively removed, and even some herds return to the drive areas. The report provides case studies of two drives: the Lunugamvehera drive and the Yala drive. In both cases, elephants experienced adverse consequences, including loss of home range, starvation, increased inter-birth intervals, and stunted growth of juveniles. The drives did not eliminate elephants from the drive areas, and HEC remained a major issue.

Electric fencing

Electric fencing is widely regarded as the most effective method to deter elephants from raiding crops. These fences operate by generating a high voltage pulse, typically ranging from 6,000 to 8,000 volts, while maintaining low amperage of 4-5 milliamperes within the fence wires. When an elephant comes into contact with the fence, the circuit is completed through the animal’s body, resulting in a powerful shock. It’s important to note that due to the low amperage, pulsating nature, and direct current design, these shocks do not cause any harm to the elephant’s life.

Protected areas only cover a small portion of the elephants’ range and are already at their maximum capacity. As a result, concentrating elephant populations in these areas leads to their decline and loss. Secondly, elephants thrive in a habitat that consists of a mix of regenerating forests and open spaces, which are predominantly found outside protected areas. Consequently, elephant densities are often higher in these non-protected areas.

Research has shown that adult male elephants are primarily responsible for conflicts, but it is difficult to restrict their movement to protected areas. Attempts to do so, such as through elephant drives, only exacerbate conflicts and make elephants more aggressive, leading to increased HEC. On the other hand, herds composed of females and young elephants cause less conflict but suffer high mortality when forced into protected areas away from their natural ranges. Therefore, coercing elephants into protected areas and confining them there results in escalating HEC and the loss of elephants.

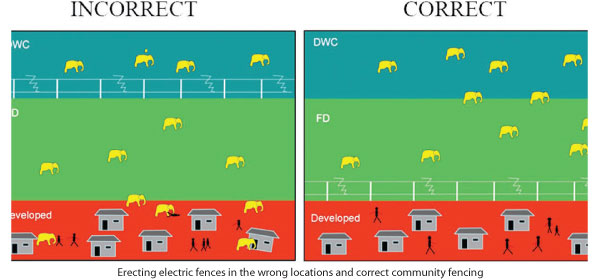

Minimising the impact of HEC on local communities is crucial in managing elephants outside protected areas. To address this, an approach of providing “village electric fencing” has been adopted led by the World Bank, supported by the Global Environment Forum (GEF). Villagers are encouraged to install fences around their settlements, which are positioned at the forest edge rather than within it. This reduces the likelihood of elephants approaching the fences and spending time trying to break through them. By involving the villagers in constructing and financing the fences, a sense of ownership is fostered, ensuring long-term fence maintenance.

Collaboration with communities, local government bodies, and administrative divisions has been instrumental in implementing these fences in various regions of Sri Lanka. Successful examples include Tammennawa, Bundala and Weerawila in the South, as well as Madadombe in the North-West.

The Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) and Divisional Secretariats have adopted the community electric fence model in the Eriyawa village in the North-West. Additionally, organisations such as JICA have assisted villagers in Ketanwewa in the South with the installation of such fences. The Centre for Conservation and Research (CCR) has been involved in planning and constructing electric fences in both Eriyawa and Ketanwewa.

Currently, efforts are under way to expand this approach and develop a government program to support community electric fencing. Collaborations with District Secretariats in the South and North-West are going on to scale up the initiative effectively.

Currently, efforts are under way to expand this approach and develop a government program to support community electric fencing. Collaborations with District Secretariats in the South and North-West are going on to scale up the initiative effectively.

Raiding of paddy fields by elephants is a significant issue contributing to HEC and rural poverty in Sri Lanka. Electric fencing has been effective in preventing crop raiding, but permanent fences around paddy fields pose maintenance challenges and negatively impact elephants.

Maintenance is crucial for the success of electric fences, but many paddy fields in Sri Lanka remain fallow for several months or even years. During fallow periods, there is no one to maintain permanent electric fences, causing them to become ineffective. Elephants become accustomed to breaking such fences, leading to increased HEC, even in well-maintained areas.

Foraging areas

Fallow paddy fields serve as important foraging areas for elephants and allow them to move between forest patches without conflict. Constructing permanent fences around paddy fields restricts elephants’ access to these resources and blocks their movement during fallow periods. As a result, elephants are forced to raid more crops for survival and may break the fences or navigate through village areas, leading to further escalation of HEC.

To address this issue, a system of temporary “paddy field fences” has been developed. These fences consist of GI tube posts with direct wire contact, making it harder for elephants to break through. The GI posts are placed in PVC tubes to prevent earthing, ensuring the fence remains energised. Farmers set up these fences at the beginning of the cultivation season and dismantle them on the day of harvest, storing them for future use. This allows elephants to utilise fallow fields while protecting the paddy during the cultivation period.

Successful pilots of temporary paddy field fences have been conducted in the South, and efforts are under way to introduce this concept to the North-West region. Collaboration with the Ministry and the Department of Agrarian Services aims to demonstrate the effectiveness of these fences and encourage the Government to establish a program supporting farmers in implementing paddy field fences.

The effectiveness of community fencing and temporary paddy field fencing was discussed at a recent ESCAMP workshop on July 12. The Ecosystem Conservation and Management Project (ESCAMP) is an ambitious program launched by the Government in collaboration with multiple stakeholders and local communities to tackle issues facing diverse areas of the island’s ecology, which includes testing the CCR’s community fencing project under its human-elephant coexistence program. Gamini Samarakoon of ENSCAMP coordinated the fencing program in the Anuradhapura district during the past two and a half years. On recent community fencing, he said that the situation has been controlled to a certain extent, but not 100 percent, and gave credit to the CCR for its methodology. Elaborating on the paddy field fences, he said, “We can erect them and after harvest we can remove those fences and we can put it back during the next season. So, this new concept was considered by ESCAMP and we are planning to erect 60 paddy field fences in two districts. The main objective of the village and agricultural community fencing was to ensure the protection of villages affected by HEC, reducing poverty and ensuring the protection of wild elephant populations, allowing human-elephant coexistence. So, that’s the basic concept behind that program”.

Setbacks

But the program was not without its share of setbacks. “Some paddy fields and privately owned forest patches had to be included in some of the village fences due to disagreement of landowners to divide their lands by the fences.”

He said that while some agreed to have fences going through their property, some others did not agree to divide their lands fearing they might lose ownership of the land outside the fence.

“Sometimes we had to include small patches of paddy fields and forest areas in the villages. So, actually this has become a lesson learned when we implemented the pilot project,” Samarakoon said.

“Firstly, we identified areas where HEC is intense. We collected data from the DWC, regional secretaries, villagers and community leaders and had a meeting. There we explained the procedure we had identified under the ESCAMP’s program. When we were talking about the procedure, some did not agree to go ahead with us. But some villagers agreed with this procedure and decided to contribute their labour for the construction and maintenance of the fence. Identification of the fence path is the next step, he said.

“We walked around the villages with two experienced field coordinators for two districts. With their approval, we identified the fence path and took GPS readings. Mapping these identified fence paths allowed us to estimate the total length of the proposed fence. With that, we can estimate the amount of equipment we need for the fence. Villagers set up a Community-Based Organisation (CBO). We asked them to open a bank account and raise a maintenance fund for the fence. We asked them to contribute Rs. 3,000 per acre. With that fund, they can maintain the fence properly,” Samarakoon said.

“We walked around the villages with two experienced field coordinators for two districts. With their approval, we identified the fence path and took GPS readings. Mapping these identified fence paths allowed us to estimate the total length of the proposed fence. With that, we can estimate the amount of equipment we need for the fence. Villagers set up a Community-Based Organisation (CBO). We asked them to open a bank account and raise a maintenance fund for the fence. We asked them to contribute Rs. 3,000 per acre. With that fund, they can maintain the fence properly,” Samarakoon said.

The villagers were asked to get approval from the Regional Secretary with the recommendation of the Grama Niladhari.

“On the recommendation of the Grama Niladhari, the Regional Secretary recommended the CBO to issue equipment. We asked them to construct an energiser hut for the fence. After the construction of the fence and after the approval of the Regional Secretary, we issued the equipment and started the construction of the fence. After the construction of the fence, we asked them to supervise the fence continuously to make it function properly. The project deployed fence supervisors daily. They used a form issued by the project. They filled it and sent it to us via WhatsApp. With the continuous supervision, we ensured the functioning of the fence properly,” he said.

Samarakoon said the paddy field fencing followed a parallel procedure with the Department of Agriculture and Development.

Community-based fencing seems like an effective solution for the HEC for now. It is after all, a well thought of solution followed by decades of study into the migratory and behaviour patterns of elephants and data gathered by experts using GPS and other technologies.

Environmental Lawyer Dr. Jagath Gunawardana said, “the human-elephant conflict cannot be looked at as an isolated problem; it should be view in the larger context of degradation and destruction of habitats where elephants live. Therefore, building fencing and physical barriers to keep the elephants away, we have to address the larger problem in the same vein. If not, having new solutions and new ways of looking at the problem will not solve the problem”.