Part 15

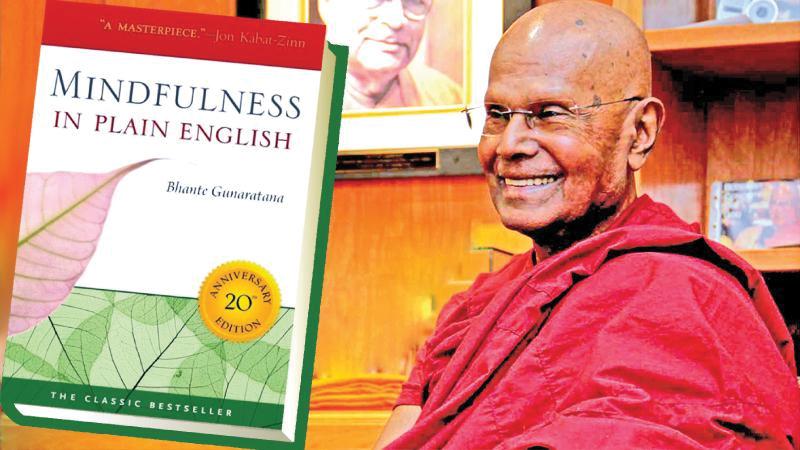

Extracted from renowned meditation guru Bhante Henepola Gunaratana’s Mindfulness in Plain English. The full text of the book will be carried in the Sunday Observer in installments.

Continued from last week

At some time, every meditator encounters distractions during practice, and methods are needed to deal with them. Many useful strategies have been devised to get you back on track more quickly than that of trying to push your way through by sheer force of will. Concentration and mindfulness go hand in hand. Each one complements the other. If either one is weak, the other will eventually be affected. Bad days are usually characterised by poor concentration. Your mind just keeps floating around. You need a method of reestablishing your concentration, even in the face of mental adversity. Luckily, you have it. In fact, you can choose from an array of traditional practical maneuvers.

1: TIME GAUGING

The first technique has been covered in an earlier chapter. A distraction has pulled you away from the breath, and you suddenly realise that you’ve been daydreaming. The trick is to pull all the way out of whatever has captured you, to break its hold on you completely so you can go back to the breath with full attention. You do this by gauging the length of time that you were distracted.

This is not a precise calculation. You don’t need a precise figure, just a rough estimate. You can measure it in minutes, or by significant thoughts. Just say to yourself, “Okay, I have been distracted for about two minutes,” or “since the dog started barking,” or “since I started thinking about money.” When you first start practising this technique, you will do it by talking to yourself. Once the habit is well established, you can drop that, and the action becomes wordless and very quick. The whole idea, remember, is to pull out of the distraction and get back to the breath. You pull out of the thought by making it the object of inspection just long enough to glean from it a rough approximation of its duration. The interval itself is not important. Once you are free of the distraction, drop the whole thing and go back to the breath. Do not get hung up in the estimate.

2: DEEP BREATHS

When your mind is wild and agitated, you can often reestablish mindfulness with a few quick deep breaths. Pull the air in strongly and let it out the same way.

This increases the sensation inside the nostrils and makes it easier to focus.

Make a strong act of will and apply some force to your attention. Concentration can be forced into growth, so you will probably find your full attention settling nicely back on the breath.

3: COUNTING

Counting the breaths as they pass is a highly traditional procedure. Some schools of practise teach this activity as their primary tactic. Vipassana uses it as an auxiliary technique for reestablishing mindfulness and for strengthening concentration. As we discussed in chapter 5, you can count breaths in a number of different ways. Remember to keep your attention on the breath. You will probably notice a change after you have done your counting. The breath slows down, or it becomes very light and refined. This is a physiological signal that concentration has become well established. At this point, the breath is usually so light or so fast and gentle that you can’t clearly distinguish the inhalation from the exhalation.

They seem to blend into each other. You can then count both of them as a single cycle. Continue your counting process, but only up to a count of five, covering the same five-breath sequence, then start over. When counting becomes a bother, go on to the next step. Drop the numbers and forget about the concepts of inhalation and exhalation. Just dive right in to the pure sensation of breathing. Inhalation blends into exhalation. One breath blends into the next in a never-ending cycle of pure, smooth flow.

4: THE IN-OUT METHOD

This is an alternative to counting, and it functions in much the same manner. Just direct your attention to the breath and mentally tag each cycle with the words, “Inhalation…exhalation,” or “In…out.” Continue the process until you no longer need these concepts, and then throw them away.

5: CANCELLING ONE THOUGHT WITH ANOTHER

Some thoughts just won’t go away. We humans are obsessional beings. It’s one of our biggest problems. We tend to lock onto things like sexual fantasies and worries and ambitions. We feed those thought complexes over years of time and give them plenty of exercise by playing with them in every spare moment. Then when we sit down to meditate, we order them to go away and leave us alone. It is scarcely surprising that they don’t obey. Persistent thoughts like these require a direct approach, a full-scale frontal attack.

Buddhist psychology has developed a distinct system of classification. Rather than dividing thoughts into classes like “good” and “bad,” Buddhist thinkers prefer to regard them as “skillful” versus “unskillful.” An unskillful thought is one connected with greed, hatred, or delusion. These are the thoughts that the mind most easily builds into obsessions. They are unskillful in the sense that they lead you away from the goal of liberation.

Skillful thoughts, on the other hand, are those connected with generosity, compassion, and wisdom. They are skillful in the sense that they may be used as specific remedies for unskillful thoughts, and thus can assist you in moving toward liberation.

Skillful thoughts, on the other hand, are those connected with generosity, compassion, and wisdom. They are skillful in the sense that they may be used as specific remedies for unskillful thoughts, and thus can assist you in moving toward liberation.

You cannot condition liberation. It is not a state built out of thoughts. Nor can you condition the personal qualities that liberation produces. Thoughts of benevolence can produce a semblance of benevolence, but it’s not the real item.

It will break down under pressure. Thoughts of compassion produce only superficial compassion. Therefore, these skillful thoughts will not, in themselves, free you from the trap. They are skillful only if applied as antidotes to the poison of unskillful thoughts. Thoughts of generosity can temporarily cancel greed. They kick it under the rug long enough for mindfulness to do its work unhindered.

Then, when mindfulness has penetrated to the roots of the ego process, greed evaporates and true generosity arises. This principle can be used on a day-to-day basis in your own meditation. If a particular sort of obsession is troubling you, you can cancel it out by generating its opposite. Here is an example: If you absolutely hate Charlie, and his scowling face keeps popping into your mind, try directing a stream of love and friendliness toward Charlie, or try contemplating his good qualities. You probably will get rid of the immediate mental image. Then you can get on with the job of meditation.

Sometimes this tactic alone doesn’t work. The obsession is simply too strong. In this case you’ve got to weaken its hold on you somewhat before you can successfully balance it out. Here is where guilt, one of man’s most misbegotten emotions, finally serves a purpose. Take a good strong look at the emotional response you are trying to get rid of. Actually ponder it. See how it makes you feel. Look at what it is doing to your life, your happiness, your health, and your relationships. Try to see how it makes you appear to others. Look at the way it is hindering your progress toward liberation. The Pali scriptures urge you to do this very thoroughly indeed.

They advise you to work up the same sense of disgust and humiliation that you would feel if you were forced to walk around with the carcass of a dead and decaying animal tied around your neck. Real loathing is what you are after. This step may end the problem all by itself. If it doesn’t, then balance out the lingering remainder of the obsession by once again generating its opposite emotion.

Thoughts of greed cover everything connected with desire, from outright avarice for material gain, all the way to a subtle need to be respected as a moral person. Thoughts of hatred run the gamut from pettiness to murderous rage.

Delusion covers everything from daydreaming to full-blown allucinations.

Generosity cancels greed. Benevolence and compassion cancel hatred. You can find a specific antidote for any troubling thought if you just think about it awhile.

6: RECALLING YOUR PURPOSE

There are times when things pop into your mind, apparently at random. Words, phrases, or whole sentences jump up out of the unconscious for no discernible reason. Objects appear. Pictures flash on and off. This is an unsettling experience. Your mind feels like a flag flapping in a stiff wind. It washes back and forth like waves in the ocean. Often, at times like this, it is enough just to remember why you are there. You can say to yourself, “I’m not sitting here just to waste my time with these thoughts. I’m here to focus my mind on the breath, which is universal and common to all living beings.” Sometimes your mind will settle down, even before you complete this recitation. Other times you may have to repeat it several times before you refocus on the breath.

These techniques can be used singly, or in combinations. Properly employed, they constitute quite an effective arsenal for your battle against the monkey mind.

Other distractions

So there you are, meditating beautifully. Your body is totally immobile, and your mind is totally still. You just glide right along following the flow of the breath, in, out, in, out…calm, serene, and concentrated. Everything is perfect. And then, all of a sudden, something totally different pops into your mind: “I sure wish I had an ice cream cone.” That’s a distraction, obviously. That’s not what you are supposed to be doing. You notice that, and you drag yourself back to the breath, back to the smooth flow, in, out, in…And then: “Did I ever pay that gas bill?” Another distraction. You notice that one, and you haul yourself back to the breath. In, out, in, out, in…“That new science fiction movie is out.

Maybe I can go see it Tuesday night. No, not Tuesday, got too much to do on Wednesday. Thursday’s better…” Another distraction. You pull yourself out of that one, and back you go to the breath, except that you never quite get there, because before you do, that little voice in your head says, “My back is killing me.” And on and on it goes, distraction after distraction, seemingly without end. What a bother. But this is what it is all about. These distractions are actually the whole point. The key is to learn to deal with these things. Learning to notice them without being trapped in them. That’s what we are here for.

This mental wandering is unpleasant, to be sure. But it is your mind’s normal mode of operation. Don’t think of it as the enemy. It is just the simple reality. And if you want to change something, the first thing you have to do is to see it the way it is.

When you first sit down to concentrate on the breath, you will be struck by how incredibly busy the mind actually is. It jumps and jib-bers. It veers and bucks. It chases itself around in constant circles. It chatters. It thinks. It fantasises and daydreams. Don’t be upset about that. It’s natural. When your mind wanders from the subject of meditation, just observe the distraction mindfully.

When we speak of a distraction in insight meditation, we are speaking of any preoccupation that pulls the attention off the breath. This brings up a new, major rule for your meditation: When any mental state arises strongly enough to distract you from the object of meditation, switch your attention to the distraction briefly. Make the distraction a temporary object of meditation. Please note the word temporary. It’s quite important. We are not advising that you switch horses in midstream. We do not expect you to adopt a whole new object of meditation every three seconds. The breath will always remain your primary focus. You switch your attention to the distraction only long enough to notice certain specific things about it. What is it? How strong is it? And how long does it last?

As soon as you have wordlessly answered these questions, you are through with your examination of that distraction, and you return your attention to the breath. Here again, please note the operant term, wordlessly. These questions are not an invitation to more mental chatter. That would be moving you in the wrong direction, toward more thinking. We want you to move away from thinking, back to a direct, wordless, and nonconceptual experience of the breath. These questions are designed to free you from the distraction and give you insight into its nature, not to get you more thoroughly stuck in it. They will tune you in to what is distracting you and help you get rid of it—all in one step.

Here is the problem: When a distraction, or any mental state, arises in the mind, it blossoms forth first in the unconscious. Only a moment later does it rise to the conscious mind. That split-second difference is quite important, because it is time enough for grasping to occur. Grasping occurs almost instantaneously, and it takes place first in the unconscious.

Thus, by the time the grasping rises to the level of conscious recognition, we have already begun to lock on to it. It is quite natural for us to simply continue that process, getting more and more tightly stuck in the distraction as we continue to view it. We are, by this time quite definitely thinking the thought rather than just viewing it with bare attention. The whole sequence takes place in a flash. This presents us with a problem. By the time we become consciously aware of a distraction, we are already, in a sense, stuck in it.

Our three questions, “What is it? How strong is it? And, how long does it last?” are a clever remedy for this particular malady. In order to answer these questions, we must ascertain the quality of the distraction. To do that, we must divorce ourselves from it, take a mental step back from it, disengage from it, and view it objectively. We must stop thinking the thought or feeling the feeling to view it as an object of inspection. This very process is an exercise in mindfulness, uninvolved, detached awareness. The hold of the distraction is thus broken, and mindfulness is back in control. At this point, mindfulness makes a smooth transition back to its primary focus, and we return to the breath.

When you first begin to practise this technique, you will probably have to do it with words. You will ask your questions in words, and get answers in words. It won’t be long, however, before you can dispense with the formality of words altogether. Once the mental habits are in place, you simply note the distraction, note the qualities of the distraction, and return to the breath. It’s a totally nonconceptual process, and it’s very quick.

The distraction itself can be anything: a sound, a sensation, an emotion, a fantasy, anything at all. Whatever it is, don’t try to repress it. Don’t try to force it out of your mind. There’s no need for that. Just observe it mindfully with bare attention. Examine the distraction wordlessly, and it will pass away by itself. You will find your attention drifting effortlessly back to the breath. And do not condemn yourself for having been distracted.

Distractions are natural. They come and they go.

Despite this piece of sage counsel, you’re going to find yourself condemning anyway. That’s natural too. Just observe the process of condemnation as another distraction, and then return to the breath.

Watch the sequence of events: Breathing. Breathing. Distracting thought arising. Frustration arising over the distracting thought. You condemn yourself for being distracted. You notice the self-condemnation. You return to the breathing. Breathing. Breathing. It’s really a very natural, smooth-flowing cycle, if you do it correctly. The trick, of course, is patience. If you can learn to observe these distractions without getting involved, it’s all very easy. You just glide through the distraction, and your attention returns to the breath quite easily. Of course, the very same distraction may pop up a moment later.

If it does, just observe that mindfully. If you are dealing with an old, established thought pattern, this can go on happening for quite a while, sometimes years. Don’t get upset. This too is natural. Just observe the distraction and return to the breath.

Don’t fight with these distracting thoughts. Don’t strain or struggle. It’s a waste.

Every bit of energy that you apply to that resistance goes into the thought complex and makes it all the stronger. So don’t try to force such thoughts out of your mind. It’s a battle you can never win. Just observe the distraction mindfully and it will eventually go away.

It’s very strange, but the more bare attention you pay to such disturbances, the weaker they get. Observe them long enough and often enough with bare attention, and they fade away forever. Fight with them and they gain strength. Watch them with detachment and they wither.

Mindfulness is a function that disarms distractions, in the same way that a munitions expert might defuse a bomb. Weak distractions are disarmed by a single glance. Shine the light of awareness on them and they evaporate instantly, never to return. Deep-seated, habitual thought patterns require constant mindfulness repeatedly applied over whatever time period it takes to break their hold. Distractions are really paper tigers. They have no power of their own. They need to be fed constantly, or else they die. If you refuse to feed them by your own fear, anger, and greed, they fade.

Mindfulness is the most important aspect of meditation. It is the primary thing that you are trying to cultivate. So there is really no need at all to struggle against distractions. The crucial thing is to be mindful of what is occurring, not to control what is occurring. Remember, concentration is a tool. It is secondary to bare attention. From the point of view of mindfulness, there is really no such thing as a distraction.

Whatever arises in the mind is viewed as just one more opportunity to cultivate mindfulness. Breath, remember, is an arbitrary focus, and it is used as our primary object of attention. Distractions are used as secondary objects of attention. They are certainly as much a part of reality as breath. It actually makes rather little difference what the object of mindfulness is. You can be mindful of the breath, or you can be mindful of the distraction.

You can be mindful of the fact that your mind is still, and your concentration is strong, or you can be mindful of the fact that your concentration is in ribbons and your mind is in an absolute shambles. It’s all mindfulness. Just maintain that mindfulness, and concentration eventually will follow.

The purpose of meditation is not to concentrate on the breath, without interruption, forever. That by itself would be a useless goal. The purpose of meditation is not to achieve a perfectly still and serene mind. Although a lovely state, it doesn’t lead to liberation by itself. The purpose of meditation is to achieve uninterrupted mindfulness. Mindfulness, and only mindfulness, produces enlightenment.

Distractions come in all sizes, shapes, and flavours. Buddhist philosophy has organised them into categories. One of them is the category of hindrances. They are called hindrances because they block your development of both components of meditation, mindfulness and concentration. A bit of caution on this term: The word “hindrances” carries a negative connotation, and indeed these are states of mind we want to eradicate. That does not mean, however, that they are to be repressed, avoided, or condemned.

Let’s use greed as an example. We wish to avoid prolonging any state of greed that arises, because a continuation of that state leads to bondage and sorrow. That does not mean we try to toss the thought out of the mind when it appears. We simply refuse to encourage it to stay. We let it come, and we let it go. When greed is first observed with bare attention, no value judgments are made. We simply stand back and watch it arise. The whole dynamic of greed from start to finish is simply observed in this way.

We don’t help it, or hinder it, or interfere with it in the slightest. It stays as long as it stays. And we learn as much about it as we can while it is there. We watch what greed does. We watch how it troubles us and how it burdens others. We notice how it keeps us perpetually unsatisfied, forever in a state of unfulfilled longing. From this firsthand experience, we ascertain at a gut level that greed is an unskillful way to run your life. There is nothing theoretical about this realisation.

All of the hindrances are dealt with in the same way, and we will look at them here one by one.

To be continued