Mahapajapati Gotami, as we know, was the step-mother nursing mom of Prince Siddhartha, later Buddha. He visits father King Suddhodana in 1PE (year 1, Post-Enlightenment). At this Encounter 1, listening to the Dhamma, Mahapajapati becomes a stream-entrant (sotapanna) while the King becomes a nonreturner (anagami).

In 5PE, he makes a second visit, father on death-bed. After the King passes away, the Buddha stays behind at hometown Kapilavatthu, spending the rainy season. With both son Nanda, and grandson Rahula, already in robes, Mahapajapati understandably has her mind on it, too. So, she approaches the Buddha, and in this Encounter 3, she makes her first Entreaty – a polite request, regarding women leaving home to train in the Path, but requesting no personal ordination.

It has come to be the prevailing view that she was denied of ordination not only at this Encounter, but in the next Encounter 4, too, still in Kapilavatthu, a year or two later when the Buddha successfully averts an intended fight over the waters of river Rohini. Inspired by a Dhamma talk, 250 soldiers (rounded figure) from each side – Koliyans on mother’s side, Sakyans on father’s side, seek and are given ordination.

The wives, led by Pajapati, making a similar request, it was to be turned down. The view goes that Pajapati was finally given ordination upon the third Entreaty at Encounter 5, a few years later at Vesali. And this was when Buddha’s hands were pushed by Ananda, when a women retinue authorised ordination, too.

But a careful look at the wordings of the very first Entreaty (at Encounter 3) seems to tell a different story. The assumption of denial may have more to do with how ‘ordination’ is characterised and seen, if also in a possible patriarchy.

As is the practice today,‘ordination’ by definition entails leaving the household. At a personal level, the candidate is required to shave off the hair, and put on the robes. He is also required to have a begging bowl. Ordination is directed by two Sangha Elders, 10 bhikkhus required for Higher Ordination Upasampada. The ordination is done in an authorised venue called the seema ‘boundary’.

Formalities and rituals

So today, Ordination basically equals formalities and rituals. No ritual, no ordination. And by the time when Mahapajapatī makes the first entreaty, PE5 (PE = Post-Enlightenment), such formalities had certainly come to be in place, of course, in relation to male Ordination. By contrast, however, and this is the critical point, in the earliest stages of the Buddha’s dispensation, there were no such formalities, all seekers, of course, being male.

We begin with the Group of Five, with whom Samana Gotama future Buddha had spent time in the bush exploring liberation. Visiting them 1PE, he was to teach them the Dhamma, addressing them simply as ‘O Bhikkhus’, when they reply “Lord”. Ordained!

No call to shave off the hair or wear robes. And many a wanderer of the time being Brahmins, they most likely had long hair, and beards, too, and were bare-bodied waist-up. There was again no issue of leaving the household since they, as wanderers, were already in the bush.

But to take the case of the first lay male to be given ordination, namely Yasa, there was no call to leave the household either, even though he came from luxury. As for his higher ordination, the Buddha’s words were, “Come, oh Bhikkhu. Well taught is the Dhamma. Lead the holy life to make a complete end of suffering”.

But to take the case of the first lay male to be given ordination, namely Yasa, there was no call to leave the household either, even though he came from luxury. As for his higher ordination, the Buddha’s words were, “Come, oh Bhikkhu. Well taught is the Dhamma. Lead the holy life to make a complete end of suffering”.

Other male seekers, too, ordination comes to be when the Buddha addresses them: “Oh, Bhikkhu”, or ‘Come Bhikkhu’ (ehi bhikkhu), or if more than one, etha bhikkhave. There is no mention of shaving off hair, or getting into robes, or even getting a begging bowl. Or leaving the household, all these merely implicit.

For all the absence of formality and ritual, when it comes to male ordination, the compilers of the Tipitaka have clearly had no hesitancy in recognising the first five and the others as being ordained. And nobody even today deny that the one- or two-word call from the Buddha did not constitute an ordination.

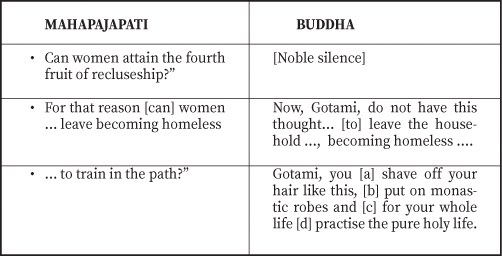

Yet, when it comes to Mahpajapati, however, the modern day chorus is loud and clear. A resounding ‘NO’! So, let us then visit her first Entreaty, made at Encounter 3, Buddha staying at Kapilavatthu following father’s death:

The response she gets for the first part of the question is a ‘noble silence’. It may be noted that when invited for alms, Buddha’s acceptance was through silence. So, this then means that he gives the hint, yes, indeed, women can “attain the fourth fruit.”, meaning Arahanthood, meaning Nibbana while alive.

His answer to the second part of the question, “Now, do not have..”, true enough, may have a negative ring to it. But, it is clearly a mere cautioning. However, the cautioning was about a) leaving the household, becoming homeless, and b) the context being in relation to women in general. But, as if in relation to her last words, “to train in the path?”, the Buddha takes his words to the personal level - “[a] shave off your hair like this, [b] put on monastic robes” and [c] “for your whole life [d] practise the pure holy life”.

Now doesn’t putting on robes mean giving up lay clothing? Doesn’t shaving off hair likewise mean leaving the lay life, as was also done by Siddhartha upon leaving the Palace? Having no hair and being in a robe are what mark a bhikkhu and bhikkhuni from the laity, then as it is today. So, what would the Buddha have meant, or the message sought to be given, with the words? How much more of a symbolism can the words imply other than ordination? Isn’t it further confirmed when the shaving and donning is to be “for your whole life”?

Pragmatic terms

To return to the caution about leaving the household life, in real pragmatic terms, could a royal lady, by this time of about the age of 55 (or possibly 80 by another tradition that she passed away at age 120), have lived in the bush? Never mind the animals, but what about the human predators?

Could she have survived the onslaughts of weather – sun, rain, wind, the castle walls and roof no longer protecting her? What about begging for food? Could she walk for hours? Would there be no harassments by the males in a society where women were mere chattels? If food collected, would there be animals going after it?

So would Pajapati leaving the household not be an invitation to suffering? To be noted is that Buddha himself was to abandon extreme self-suffering, in an experiential understanding, the Middle Path being the way. Additionally, would such materialistic impediments not stand in the way of living a spiritual life?

On the other hand, would living in the Palace itself not be supportive of a lifetime commitment and practice? Would it be an impediment to her spiritual life? Husband passed away, and son Nanda and grandson Rahula taken to a monastic life, who would be in her way, physically as also psychologically.

The only ones interacting with her would be her female attendants. Would they be in her way? Rather, would they be not attending to her personal needs? Would such attention be an attraction, back to the lay life to one who has cut off the hair and donned the robes, especially for one already a Sotapanna? Indeed if any, she could only serve as a model for the attendants themselves, regardless of their interest in Ordination.

So, in essence, then, the palace would have been the perfect fit – a peaceful environment, guaranteeing food, safety and security. Indeed this may well have been the context that prompts the Buddha listing an ‘empty house’ (sunnagara) as the third option for living, in addition to the bush and under a tree.

If this be the case then, that would show that Mahapajapati was by no means denied ordination, even when she had not even asked for it. What we see is the Buddha, in his pragmatic creativity, finding a way of allowing ordination, not denying.

So, while the physical going forth, i.e., leaving the palace, had been cautioned against, she is being guided along into a psychological going forth, this for a full lifetime. In sum, then, it can be said that Mahapajapati Gotami, indeed, was allowed to ‘go forth’, and ordained.

Third and final Entreaty

Another piece of evidence for this contention comes from the third and final Entreaty. Mahapajapati making her way to the Buddha in Vesali, with a number of other ladies, asks the same question - as to whether women could come by the fourth recluseship. Laying down a set of eight Vinaya Rules, called Garudhamma ‘Principles of Respect’, the Buddha specifically says that accepting them would constitute the higher ordination (upasampada) for Mahapajapati. And, of course, only one with an initial ordination, pabbajja, qualifies for the higher ordination? So when was the initial ordination then given? And the obvious context would be the initial Entreaty.

Both levels of ordination were given by the Buddha only in words. If we need any precedent in relation to male ordination, we have the case of Mahakassapa. It was a distinct form of ordination by “accepting an instruction”.

While this method of ordination is not shown in the Vinaya, has the one responsible for the First Council ever been considered to be not ordained? So, it is then the same method that is used by the Buddha in relation to Mahpajapati Gotami as well ordaining her.

But still, if the case has still not been made, there is the case of the Buddha making “exceptions”, an example being in relation to Subhadda, the last to get ordained under him. The rule that had come to be established by now was that a disciple of another teacher looking for discipleship under the Buddha was to mark time for four months before being admitted.

And, of course, upasampadā was to be given after several years of pabbajjā. But says the Buddha, “I make individual exceptions”, and then he asks Ananda to ordain him in his very presence, at both levels. So asking Pajapati to shave off and put on robes can be seen as an exception made by the Buddha. That would then take the last straw out of the hat of misreading!

Another point to be critically noted is that Mahapajapati comes to be ordained even when she had not specifically asked for it! In doing so, the Buddha can be said to achieve two goals. One is to create conditions for the personal liberation of his nursing mom, in an expression of gratitude, katannuta, a rare value as pointed out by him. And the second is that by admitting this single female to the monastic life, as in the case of Yasa, the Buddha was also opening the door for women’s ordination in general, a lake getting a beginning with a single drop of water.

What the pragmatic creativity shows then is a clear interest to build a bhikkhuni sangha, and no reluctance, as is the run of the mill thinking. Buddha charactering himself as ‘forward looking’ in this context should also dispel the myth that his hands were pushed by Ananda.

The best moment

If male ordination was now a grown up plant, it began with a single seed, namely, Kondañña, the first to gain insight to the Buddha’s teachings. Likewise can the Buddha’s proactive offer to Mahpajapati Gotami be seen, at the deeper level, as the first single seed towards the plant(ing) of female ordination, even though there was no formal ritual, at the initial pabbajja or the later upasampada.

Disallowing a collective ordination up until the right time would, of course, have no bearing on Mahapajapati Gotami herself, already on the Path. There could have been no better conditions than asking her to wear monastic robes with hair shaven, and reside in an Empty House, in a self-isolation.

So, then is there a double standard in relation to ordination? An apple to apple comparison then would be early male initiation to early female initiation, while apples to oranges would be early female initiation to late male initiation.

In conclusion, we can say that just as in relation to male ordination in the earliest stages, entailing no ritual, Mahapajapati was indeed ordained at the very first Entreaty. The Buddha can also be said to be confirming in action his noble silence in response to the specific question if women can attain to the fourth recluseship.

Ven. Bhikkhu Mihita was formerly Prof. Suwanda H. J. Sugunasiri, a US Fulbright scholar, the Founder of Nalanda College of Buddhist Studies, Toronto, and Pioneer in Canadian Buddhism and introducer of Theravada Buddhism to Cuba. His latest initiative is the Buddhist Literary Festival Canada.