As the Christmas approach, there seems to be a new spirit in the air. A spirit of hope that things are getting better and that there is finally a light at the end of the tunnel. With the holidays now right up ahead, people are eager to get back together with their loved ones, in an atmosphere of mutual enjoyment and celebration.

Multiple generations will gather under the same roof and Christmas will bring delight to all, while the arrival of a brand-new year shortly afterward will buoy everyone’s mood as they look forward to happier times. Reconnecting with loved ones over the holidays is going to do wonders for people’s outlook, even more so than they might expect. Renewing and refreshing relationships is what Christmas is all about.

Christians around the world celebrate the glorious feast of Nativity - Jesus’ Birth on December 25. In the liturgical year, Christmas is preceded by the season of Advent and initiates the Christmastide, which lasts twelve days. Christmas is characterised by special liturgies, joyful carols, brightly wrapped gifts and festive foods. “Christmas” is a shortened form of “Christ’s mass.”

The traditional Christmas narrative, the Nativity of Jesus, delineated in the New Testament says that Jesus Christ was born in Bethlehem. When Joseph and Mary arrived in the city, the inn had no room and so they were offered a stable where the Christ Child was soon born, with angels proclaiming this news to shepherds who then further disseminated the information.

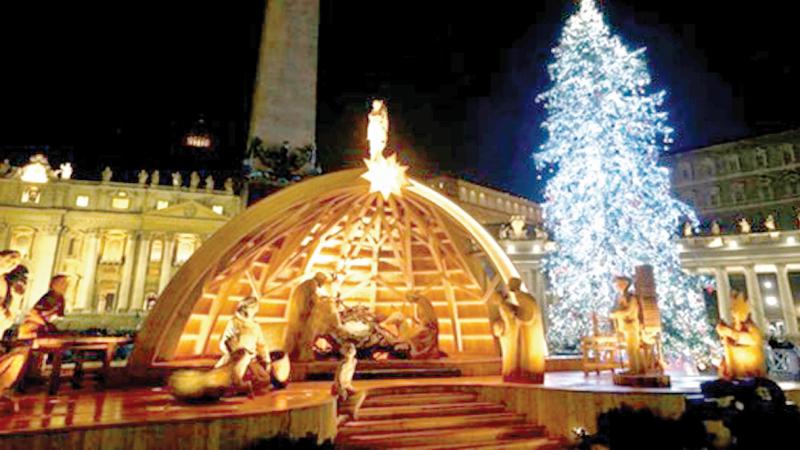

Christmas tree and Nativity Scene

On December 3, 2022, Pope Francis invited the faithful to two “human and Christian attitudes” that we can learn from the Christmas tree and the Nativity scene. Pope said: The tree and Nativity display are two signs that continue to charm young and old. The tree, with its lights, reminds us of Jesus who comes to illuminate our darkness, our existence often closed in the shadow of sin, fear, and pain.

And the tree suggests to us a further reflection: Like trees, people too need roots. Because only if it is rooted in good soil can it stay firm, grow, “mature,” and resist the winds that shake it, becoming a point of reference to those who look at it. But, without roots none of this can happen; without firm foundation it remains unstable. It is important to safeguard the roots, in life as well as faith.

And the tree suggests to us a further reflection: Like trees, people too need roots. Because only if it is rooted in good soil can it stay firm, grow, “mature,” and resist the winds that shake it, becoming a point of reference to those who look at it. But, without roots none of this can happen; without firm foundation it remains unstable. It is important to safeguard the roots, in life as well as faith.

In this regard, the apostle Paul reminds us of the foundation in which to root our lives to remain firm: he says to remain “rooted in Jesus Christ” (Colossians 2:7). This is what the Christmas tree reminds us of: to be rooted in Jesus Christ.

And so, we come to the Nativity scene, which speaks to us of the birth of the Son of God who became man to be close to each one of us. In its genuine poverty, the Nativity scene helps us to rediscover the true richness of Christmas, and to purify ourselves of so many aspects that pollute the Christmas landscape.

Simple and familiar, the Nativity scene recalls a Christmas that is different from the consumerist and commercial Christmas: it is something else; it reminds us how good it is for us to cherish moments of silence and prayer in our days, often overwhelmed by frenzy.

Silence fosters contemplation of the Child Jesus helps us to become intimate with God, with the fragile simplicity of a tiny newborn baby, with the meekness of his being laid down, with the tender affection of the swaddling clothes that envelop him.

And if we genuinely want to celebrate Christmas, let us rediscover through the Nativity scene the surprise and amazement of smallness, the smallness of God, who makes himself small, who is not born in the splendor of appearances, but in the poverty of a stable. And prayer is the best way to say thank you before this gift of free love, to say thank you to Jesus who wishes to enter our homes and our hearts.

Yes, God loves us so much that he shares our humanity and our lives. He never leaves us by ourselves, He is at our side in all circumstances, in joy as in sorrow. Even in the worst moments, He is there, because He is the Emmanuel, the God with us, the light that illuminates the darkness and the tender presence that accompanies us on our journey, concluded the Holy Father.

Jesus’ birth

There is no mention of birth celebrations in the writings of early Christian writers such as Irenaeus (c. 130–200) or Tertullian (c. 160–225). Origen of Alexandria (c. 165–264) goes as far as to mock Roman celebrations of birth anniversaries - a strong sign that Jesus’ birth was not celebrated at all at this point.

In the second century AD, further details of Jesus’ birth and childhood are related in apocryphal writings such as the Infancy Gospel of Thomas and the Proto-Gospel of James. These texts provide everything from the names of Jesus’ grandparents to the details of his education but not the date of his birth.

Finally, in about AD 200, a Christian teacher in Egypt refers to the date Jesus was born. According to Clement of Alexandria, several different days had been proposed by various Christian groups. Clement writes: “There are those who have determined not only the year of our Lord’s birth, but also the day; and they say that it took place in the 28th year of Augustus, and in the 25th day of Pachon.

The earliest mention of December 25 as Jesus’ birthday comes from a mid-fourth century Roman almanac. The first date listed, December 25, is marked: “Christ was born in Bethlehem of Judea.” In about AD 400, Augustine of Hippo mentions a local dissident Christian group, the Donatists, who kept Christmas festivals on December 25.

Clearly there was great uncertainty, but also a considerable amount of interest, in dating Jesus’ birth in the late second century. By the fourth century, however, we find references to two dates that were widely recognized and now also celebrated as Jesus’ birthday: December 25 in the Western Roman Empire and January 6 in the East. For most Christians, December 25 would prevail, while January 6 eventually came to be known as the Feast of the Epiphany.

So, almost three hundred years after Jesus was born, we finally find people observing his birth in mid-winter. There are two theories today: one extremely popular, the other less often heard outside scholarly circles, though far more ancient.

The first Christmas

The most loudly touted theory about the origins of the Christmas date is that it was borrowed from pagan celebrations. Christmas, the argument goes, is really a spin-off from these pagan solar festivals. According to this theory, early Christians deliberately chose these dates to encourage the spread of Christmas and Christianity throughout the Roman world.

Despite its popularity, this theory of Christmas’s origins has its problems. It is not found in any ancient Christian writings. The church father Ambrose (c. 339–397), described Christ as the true son, who outshone the fallen gods of the old order. But early Christian writers never hint at any recent calendric engineering; they clearly do not think the date was chosen by the church.

It is not until the 12th century that we find the first suggestion that Jesus’ birth celebration was deliberately set at the time of pagan feasts. A marginal note on a manuscript of the writings of the Syriac biblical commentator Dionysius bar-Salibi states that in ancient times the Christmas holiday was shifted from January 6 to December 25.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Bible scholars spurred on by the new study of comparative religions latched on to this idea. They claimed that because the early Christians did not know when Jesus was born, they simply assimilated the pagan solstice festival for their own purposes, claiming it as the time of the Messiah’s birth and celebrating it accordingly.

More recent studies have shown that many of the holiday’s modern trappings do reflect pagan customs borrowed much later, as Christianity expanded into Northern and Western Europe. The Christmas tree, for example, has been linked with late medieval druidic practices. This has only encouraged modern audiences to assume that the date, too, must be pagan.

Most significantly, the first mention of a date for Christmas (c. 200) and the earliest celebrations that we know about (c. 250–300) come in a period when Christians were not borrowing heavily from pagan traditions of such an obvious character. Yet, in the first few centuries AD, the persecuted Christian minority was concerned with distancing itself from the larger, public pagan religious observances, such as sacrifices, games, and holidays. This was still true as late as the violent persecutions of the Christians conducted by the Roman emperor Diocletian between AD 303 and AD 312.

Jesus’ birth and death

Strange as it may seem, the key to dating Jesus’ birth may lie in the dating of Jesus’ death at Passover. This view was first suggested to the modern world by French scholar Louis Duchesne in the early 20th century and fully developed by American Thomas Talley in more recent years. But they were certainly not the first to note a connection between the traditional date of Jesus’ death and his birth.

Around AD 200, Tertullian of Carthage reported the calculation that the 14th of Nisan (the day of the crucifixion according to the Gospel of John) in the year Jesus died was equivalent to March 25 in the Roman calendar. March 25 is, of course, nine months before December 25; it was later recognised as the Feast of the Annunciation. Thus, Jesus was believed to have been conceived and crucified on the same day of the year. Exactly nine months later, Jesus was born, on December 25.

Augustine, too, was familiar with this association. In ‘On the Trinity’ (c. 399–419) he writes: “For Jesus is believed to have been conceived on March 25, upon which day also he suffered; so, the womb of the Virgin, in which he was conceived, where no one of mortals was begotten, corresponds to the new grave in which he was buried, wherein was never man laid, neither before him nor since. But he was born, according to tradition, upon December 25.”

It reflects ancient and medieval understandings of the whole of salvation being bound up together. One of the most poignant expressions of this belief is found in Christian art. In numerous paintings of the angel’s Annunciation to Mary - the moment of Jesus’ conception, the baby Jesus is shown gliding down from heaven on or with a small cross; a visual reminder that the conception brings the promise of salvation through Jesus’ death.

Christmas on December 25

Although the month and date of Jesus’ birth are unknown, the church in the early fourth century fixed the date as December 25. Most Christians celebrate on December 25 in the Gregorian calendar, which has been adopted universally in the civil calendars used in countries throughout the world.

For Christians, believing that God came into the world in the form of man to atone for the sins of humanity, rather than knowing Jesus’ exact birth date, is the primary purpose in celebrating Christmas. The celebratory customs associated in various countries with Christmas have a mix of pre-Christian, Christian, and secular themes and origins.

Many popular customs associated with Christmas developed independently and include gift giving; completing an Advent calendar or Advent wreath; Christmas music and carolling; viewing a Nativity play; an exchange of Christmas cards; church services; a special meal; and the display of various Christmas decorations, including Christmas trees, Christmas lights, nativity scenes, garlands, wreaths, mistletoe, and holly.

The prevailing atmosphere of Christmas has also continually evolved since the holiday’s inception. Celtic winter herbs such as mistletoe and ivy, and the custom of kissing under a mistletoe, are common in modern Christmas celebrations. In Germanic language-speaking areas, numerous elements of modern Christmas folk custom and iconography may have originated from Yule, including the Yule log, Yule boar, and the Yule goat.

In addition, several closely related and often interchangeable figures, known as Santa Claus, Father Christmas, Saint Nicholas, and Christ kind, are associated with bringing gifts to children during the Christmas season and have their own body of traditions and lore.

Christmas carols, card, and tree

The Catholic Church promoted the festival in a more religiously oriented form. In 1629, John Milton penned ‘On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity,’ a poem that has since been read by many during Christmastide. King Charles I of England directed his noble people to return to their landed estates in midwinter to keep up their old-style Christmas generosity. The book, The Vindication of Christmas (London, 1652), published Old English Christmas traditions.

In 1832, the future Queen Victoria wrote about her delight at having a Christmas tree, hung with lights, ornaments, and presents placed round it. The revival of the Christmas Carol began with William Sandys’s “Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern” (1833), with the first appearance in print of “The First Noel”, “I Saw Three Ships” and “Hark the Herald Angels Sing.” In 1843, Sir Henry Cole produced the first commercial Christmas card.

In 1843, Charles Dickens authored the novel ‘A Christmas Carol,’ which helped revive the “spirit” of Christmas and seasonal merriment. Its instant popularity played a significant role in portraying Christmas as a holiday emphasizing family, goodwill, and compassion. Dickens influenced many aspects of Christmas that are celebrated today such as family gatherings, seasonal food and drink, dancing, and a festive generosity of spirit. A prominent phrase from the tale, “Merry Christmas,” was popularized following the appearance of the story.

In Britain, the Christmas tree was introduced in the early 19th century by Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, wife of King George III. An image of the British royal family with their Christmas tree at Windsor Castle created a sensation when it was published in the Illustrated London News in 1848. A modified version of this image was published in the United States in 1850. By the 1870s, putting up a Christmas tree had become common in America.

The interest in Christmas had been revived in the United States in 1820s by Washington Irving which appear in his The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. and “Old Christmas.” In 1822, Clement Clarke Moore authored the poem ‘A Visit From St. Nicholas’. While the celebration of Christmas was not yet customary in some regions in the United States, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow detected “a transition state about Christmas in New England” in 1856.