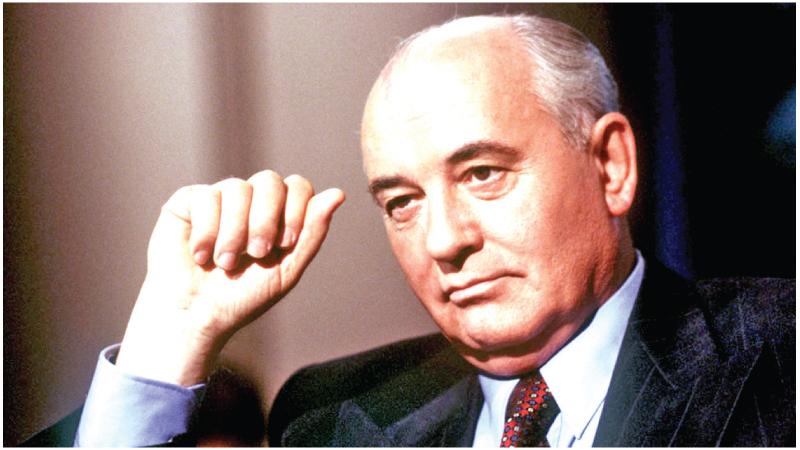

Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union, who embarked on a path of radical reform that brought about the end of the Cold War, reversed the direction of the nuclear arms race and relaxed Communist Party controls in hopes of rescuing the faltering Soviet state but instead propelled it toward collapse, died August 30 in Moscow. He was 91.

For the sheer improbability of his actions and their impact on the late 20th century, Gorbachev ranks as a towering figure. In 1985, he was chosen to lead a country mired in socialism and stultifying ideology. In six years of cajoling, improvised tactics and increasingly bold risks, Gorbachev unleashed immense changes that eventually demolished the pillars of the state.

The Soviet collapse was not Gorbachev’s goal, but it may be his greatest legacy. It brought to an end a seven-decade experiment born of Utopian idealism that led to some of the bloodiest human suffering of the century. A costly global confrontation between East and West abruptly ceased to exist. The division of Europe fell away. The tense superpower hair-trigger nuclear standoff was eased, short of Armageddon.

Revolution

None of it could have happened but for Gorbachev. Along the way, he let loose a revolution from above within the Soviet Union, prodding and pushing a stagnant country in hopes of reviving it. In nearly six years of high drama and breathtaking transformation, Gorbachev pursued ever-larger ambitions for liberalisation, battling inertia and a stubborn old guard.

Archie Brown, an emeritus professor of politics at the University of Oxford’s St. Antony’s College and an authority on Gorbachev, has written that openness and pluralism were among his singular achievements in a country that for hundreds of years had been shackled by authoritarian rule under the czars and Soviet leaders. Gorbachev introduced the first genuinely competitive elections for a legislature, allowed civil society to take root and encouraged open discussion of dark passages in Soviet history.

At the same time, Brown said, Gorbachev suffered failures, including his effort to break the grip of central planning on the economy in reforms known as perestroika, which got a start but never went far enough, and his inability to satisfy ambitions for sovereignty among restive Soviet nationalities, which contributed to the centrifugal forces that broke up the country.

Many of Gorbachev’s most remarkable accomplishments came to haunt him. Liberalisation of the system “brought every conceivable long-suppressed problem and grievance to the surface of Soviet political life,” Brown recalled. “Gorbachev’s political in-tray became monumentally overloaded.”

After a failed coup attempt by hard-liners in 1991, a weakened Gorbachev finally relinquished power to even more radical reformers led by Russian President Boris Yeltsin. The Soviet flag came down from the Kremlin on December 25, 1991.

Gorbachev did not set out to lower that flag. He was very much a product of the system and the tumultuous events that spanned his lifetime, from Stalin’s terror and the unimaginable losses of World War II, through the hardships, thaws, triumphs, dashed expectations and stagnation of the postwar years.

Over many years, Gorbachev came to see a huge chasm that existed between the reality of Soviet day-to-day life, often shabby and poor, and the artificial slogans of the party and leadership about a bright future under communism.

Many others also saw this gap and shrugged, but what made Gorbachev different is that he was shocked by it. By the time he became Soviet leader, he had fully absorbed the abysmal reality but had little understanding of how to fix it. He hoped that unleashing forces of openness and political pluralism would heal the other maladies.

They could not.

Mikhail Sergeievich Gorbachev was born on March 2, 1931, in the small village of Privolnoye, in the black-earth region of Stavropol in Southern Russia. His parents, Sergei and Maria, worked the land in a village that was little changed over centuries.

Gorbachev spent much of his childhood as the favorite of his mother’s parents: He often lived with them. His maternal grandfather, Pantelei, was remembered by Gorbachev as a tolerant man and immensely respected in the village. In those years, Gorbachev was the only son; a brother was born after the war, when Mikhail was 17 years old.

Famine struck the region in 1933, when Gorbachev was 2. Joseph Stalin had launched the mass collectivisation of agriculture, a brutal process of forcing the peasants into collective farms and punishing those known as kulaks who were somewhat better off. The collectivisation destroyed traditional patterns of farming. A third to a half of the population of Privolnoye died of hunger.

The Great Terror affected Gorbachev, too. His grandfather on his father’s side, Andrei, rejected collectivisation and tried to make it on his own. In the spring of 1934, Andrei was arrested and accused of failing to fulfill the sowing plan set by the Government for peasants.

“But no seeds were available to fulfill the plan,” Gorbachev recalled of the absurdity of the charge. Andrei was declared a “saboteur” and sent to a prison camp for two years, but released early, in 1935. On his return, he became a leader of the collective farm.

University education

Gorbachev entered Moscow State University, the country’s most prestigious, in September 1950, a peasant boy in the bustling metropolis. He arrived with only a village school education, and friends who had acquired more learning in their earlier years often teased him. Gorbachev joined the Communist Party in 1952.

By his own account, Gorbachev was taken with Soviet ideology, like many of his generation, who hoped that war, famine and the Great Terror were things of the past, and believed they were building a new society, with social justice and people power. When Stalin died in 1953, Gorbachev joined the crowds lining up to pay their respects in Red Square.

But in the years that followed, Gorbachev came to see Stalin differently. At the 20th Party Congress, on February 25, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev delivered his famous “secret speech” denouncing Stalin’s personality cult and use of violence and persecution.

Only after the speech, Gorbachev recalled, “did I begin to understand the inner connection between what had happened in our country and what had happened to my family.”

“The document containing Khrushchev’s denunciations circulated briefly within the party, and then it was withdrawn,” Gorbachev recalled. “But I managed to get my hands on it. I was shocked, bewildered and lost. It wasn’t an analysis, just facts, deadly facts. Many of us simply could not believe that such things could be true. For me, it was easier. My family had itself been one of the victims of the repression of the 1930s.”

Gorbachev later frequently called Khrushchev’s speech “courageous.” It was not a total break with the past, but it was a break nonetheless.

While at the university, Gorbachev met and married Raisa Titorenko, a bright philosophy student. She initially shunned the village boy, but he eventually charmed her.

After the university, Gorbachev decided on a career with the Komsomol, the party’s youth division, as deputy head of the “agitation and propaganda department.” This was a conformist career path.

Gorbachev threw himself into the work, honing his speaking skills, often making trips around the Stavropol region to exhort young people to be good socialists and believe in the party. In an early assignment, he was sent out to a local district to extol Khrushchev’s speech on Stalin.

Gorbachev moved up rapidly through the party ranks in Stavropol to become the highest-ranking official, the first secretary, from 1970 to 1978. Gorbachev was a party leader but was confronted almost daily with the absurdity of the system he served. He recognised the disconnect between the bureaucrats of central planning in Moscow, who issued orders to do this and that, and the reality on the ground in farms and cities, where the orders often made no sense. The demands were ignored, statistics faked, budgets spent with no result, and anyone who didn’t conform was punished.

In 1978, Gorbachev wrote a lengthy memo on the problems of agriculture that called for giving “more independence to enterprises and associations” in deciding key production and money issues. But there is no evidence that these ideas ever took root very widely, and Gorbachev was definitely not a radical.

Gorbachev visited Italy, France, Belgium and West Germany. What he saw in these relatively prosperous democracies was far different from what he had been shown in Soviet propaganda books, film and radio broadcasts. Gorbachev realised multiple voices were allowed to challenge the power structure. And, he said, “People there lived in better conditions and were better off than in our country. The question haunted me: Why was the standard of living in our country lower than in other developed countries?”

Upward mobility

In a move that took him upward in the Soviet power structure, Gorbachev was elected a secretary of the Central Committee, and he was put in charge of agriculture in Leonid Brezhnev’s final years in power. The general secretary was ill, and some Politburo meetings lasted no longer than 15 or 20 minutes. The country was in serious trouble economically.

From the time Gorbachev arrived in Moscow in November 1978, through the early 1980s, an intense Kremlin power struggle played out between an old guard, bastions of the party and the military, and a handful of reformers, most of whom were academics with fresh ideas but no power base. When Brezhnev died in 1982, hopes were raised that his successor, the former KGB boss Yuri Andropov, would end the long stagnation. Andropov promoted a group of younger officials, including Gorbachev, whom he had mentored. Gorbachev brought some of the academic reformers to his side.

Five weeks after Ronald Reagan was reelected to a second term, in December 1984, Gorbachev made a landmark trip to London, where he left a strong impression. He called attention to the dangers of nuclear war and emphasised Soviet fears of an arms race in space. He promised “radical reductions” in nuclear weapons.

In substance, Gorbachev did not change Soviet policy, but his youthful and vigorous style spoke volumes. He seemed to promise a more flexible approach, a sharp contrast with the rigidity of the past.

Just after the visit, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher gave an interview to the BBC. In her first answer to a question, she said: “I like Mr Gorbachev. We can do business together.”

On the evening of Sunday, March 10, 1985, Gorbachev took a call from the Kremlin doctor, Yevgeny Chazov. Chernenko had died of a heart ailment and complications from emphysema. The next day, Gorbachev was selected to be the new general secretary.

Gorbachev has recalled that he had a long talk with Raisa early in the morning of March 11, strolling the garden paths of their dacha outside of Moscow just before dawn, talking about the events and the implications.

Gorbachev told her he had been frustrated all the years in Moscow, having not accomplished as much as he wanted, always hitting a wall. To really get things done, he would have to accept the job. “We can’t go on living like this,” he said.

(Condensed from the Washington Post)