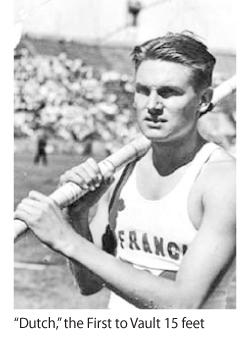

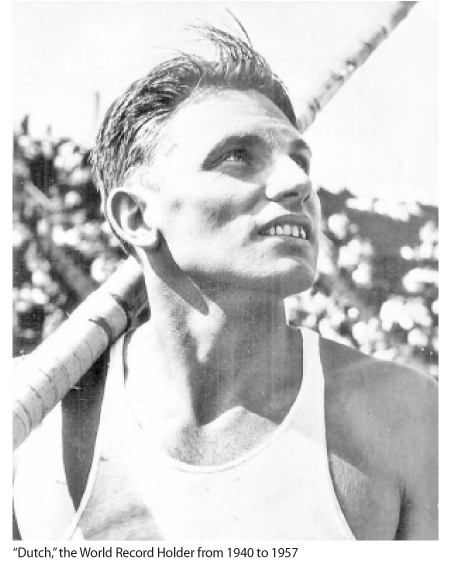

Cornelius “Dutch” Warmerdam was an American Pole Vaulter who held the world record between 1940 and 1957. These were the World War II years, and Warmerdam was an ensign and a Lieutenant of the United States Navy. The Olympic Games of 1940 and 1944 were cancelled due to the World War II and he never had the chance to win Olympic gold medals that surely would have been his, yet his place in history doesn’t require that at all.

No other athlete in the world has ever dominated an event as did “Dutch” Warmerdam in the pole vault. He was the first man to clear 15 feet, accomplishing that feat on April 13, 1940. Over the next two years, he raised the world record to 15’ 7 ¾” outdoors, a mark that remained unbroken for 15 years. He also held the world indoor best at 15’ 8 ½” for 16 long years. Overall, he had 43 highest vaults over 15 feet at a time when no other vaulter in the world had yet cleared 15 feet.

His spectacular and unrivalled streak with outdoor and indoor world records came to an end with his retirement from senior competitions in 1944, due to exigencies in Naval service, though he continued to vault into his sixties. In 1942, he won the James E. Sullivan Award. His last competition was the 1944 National Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) championships. He was inducted into the International Association of Athletics Federations ‘Hall of Fame’ in 2014.

His spectacular and unrivalled streak with outdoor and indoor world records came to an end with his retirement from senior competitions in 1944, due to exigencies in Naval service, though he continued to vault into his sixties. In 1942, he won the James E. Sullivan Award. His last competition was the 1944 National Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) championships. He was inducted into the International Association of Athletics Federations ‘Hall of Fame’ in 2014.

Birth and Career

Cornelius Warmerdam was born on June 22, 1915 in Long Beach, California. His parents were Adrianus and Gertrude Warmerdam. His father had emigrated from the Netherlands and he was their third son. As a result of his ancestry, he was more commonly known as “Dutch.” Warmerdam was an unassuming and bright youngster who grew up in Hanford, California.

Warmerdam got his start in pole vaulting in his backyard using the limb of a peach tree and landing in a pit of piled up dirt. He was discovered by the local track coach and vaulted for Hanford High School until his graduation in 1932.

He worked on his father’s 40-acre farm picking peaches and apricots for the next year and a half before a sporting goods salesman, tipped off the high school track coach, to watch Warmerdam clear a crossbar more than twice his 6-foot height while vaulting alongside a spinach patch.

The salesman shared with Flint Hanner, the Coach of Fresno State University about what he saw, and Warmerdam began vaulting for Fresno State in spring 1934 and achieved a best clearance of 14’ 1¾”. He later competed for the San Francisco Olympic Club during which he won or tied nine AAU titles, seven of them outdoors.

He didn’t advance to the Berlin 1936 Olympic trials, but he raised his best to 14’ 4” in 1937 and won the Pan American Games in Dallas in his final year at Freson State.

He won the first of six AAU titles in 1938 and set a world indoor record of 14’ 6⅛” in 1939, but his weight increased to 180 pounds in early 1940 when he was teaching history and geometry at the high school level. With his weight reduced to 170 pounds, he cleared 14’ 4” in a competition at Stanford.

In 1937, he suddenly started to vault really competitively against the two best in the world at the time, Early Meadows, the 1936 Olympic champion, and Bill Sefton, who was as good as Meadows. All three cleared 14’ 7⅝” that year. Sefton and Meadows actually approached 15 feet, and Meadows set a world record, vaulting 14’ 10½”.

Warmerdam kept on vaulting after college and reached his full development from 1940 through 1944 when he was in his late 20s. Vaulting throughout his career with a bamboo pole, Warmerdam was the first vaulter to clear 15 feet (4.57m), accomplishing that feat at UC Berkeley on April 13, 1940. However, that achievement was not ratified for a world record, and his later vault of 15’ 1” (4.60m) on June 29, 1940 was the first ratified jump over 15 feet.

On Warmerdam’s world record, Cordner Nelson wrote in his book “Track and Field – THE GREAT ONES”: “In one marvellous second, over that crossbar came his transition from a good vaulter to world record holder.” Warmerdam raised the record to 15’ 1⅛” in the 1940 AAU championships in Fresno before clearing 15’ 2⅝” in a competition at Stanford in 1941. He raised the record to 15’ 4 ¼” and then to 15’ 5¾” in the Compton Invitational two months later.

No one else topped that height for more than a decade and, finally it was accomplished by a second man, Robert “Bob” Eugene Richards (who became the only two-time male Olympic champion), it wasn’t done with the old bamboo pole that Warmerdam always used, but with the new metal pole. No other athlete in all sports history has ever been so far better than the next best men, and over such a span of years.

He was consistently a foot or a foot and a half better than his nearest rivals in an event where the margin is usually no more than a couple of inches. After he retired in 1947, it was as if the clock had suddenly been set back in the pole vault, with men vaulting 13’ 6” and 14’ winning national championships again.

Warmerdam competed during an era when poles were made of bamboo and landing pits were piles of wood shavings. His world outdoor record of 15’ 7¾” in 1942 lasted 15 years, and his world indoor record of 15’ 8½” in 1943 stood for 16 years. His outdoor record was broken by Robert Allen “Bob” Gutowski in 1957 using a metal pole.

Warmerdam won the James E. Sullivan Award in 1942 as the nation’s outstanding amateur athlete, However, he continued competing as an early practitioner of Masters athletics. He still is ranked in the world all-time top ten list in the M60 (from 60th birthday to the day before 65th birthday) Decathlon.

He turned in the finest performance of his career in March 1943 when he cleared a world indoor record of 15’ 8½” in the Chicago Relays before missing three times at 16’ ½”.

Warmerdam cleared 15 feet nine times during the 1943 outdoor season, but was able to do it only once in 1944 when his duties as a United States’ Navy Lieutenant stationed at Monmouth College in Illinois limited his training in a greater way.

Warmerdam, who was an assistant track and field coach at Fresno State University from 1947 to 1960 and the Head Coach from 1961 until his retirement in 1980. His team won the second NCAA Men’s Division II Outdoor Track and Field Championships, essentially at home at Ratcliffe Stadium.

Fresno State named its track stadium “Warmerdam Field” in his honour. The street north of the Kings County Library in Hanford was renamed for “Dutch Warmerdam.” Dutch is a member of the National Track and Field ‘Hall of Fame’ and the Millrose Games ‘Hall of Fame,’ besides IAAF ‘Hall of Fame.’

Pole Vault at Olympic Games

American Cornelius Warmerdam had dominated the pole vault during World War II, breaking the world record three times and increasing the record a total of 23 centimetres; however, he had retired in 1944. The men’s pole vault was part of the athletics programme at the 1948 Summer Olympics. Nineteen athletes from 10 nations competed.

The final was won by American Guinn Smith with his last attempt clearance of 4.30. This was the 11th appearance of the event, and Smith’s win was the United States’ 11th consecutive victory as well. Prior to the competition, the world record belonged to Cornelius Warmerdam of the United States for his 15’ 7¾” at Modesto, United States on May 23, 1942. In London 1948, the first Olympics held after the war, the winning height was 14’ 1¼”.

Four years later at Helsinki 1952, and eight years later 1956 at Melbourne, Richard’s winning heights still fell a little short of the 15-foot mark, a height Warmerdam had bettered, substantially, 43 times over the previous dozen years. No wonder that it was said about him by an old Olympic medallist, Nat Carmel, that “he was the only all-time, indisputable, supreme champion the athletic world has ever known.”

World Record Progression

Warmerdam surpassed the pole vault record seven times in a four-year span, and three of those marks were ratified as world records. On May 29, 1937, Earle Meadows of the United States cleared 4.54m (14’ 10½”) in Los Angeles, United States to improve on the world record. It stood for 3 years, before Cornelius Warmerdam of the United States cleared 4.60 m (15’ 1”) in Fresno, USA on June 29, 1940.

Warmerdam improved the world record to 4.72 m (15’ 5¾”) in Compton, USA on June 26, 1941. Then he improved the record further to 4.77 m (15’ 7¾”) in Modesto, USA on May 23, 1942. This record of Cornelius Warmerdam stood for 14 long years before surpassed by Robert Allen “Bob” Gutowski of the United States (silver medallist at Melbourne 1956 Olympics) clearing 4.78 m (15’ 8”) in Palo Alto, USA on April 27, 1957.

Personal Life

“Dutch” Warmerdam tied the knot with Juanita Anderson on August 29, 1940. Their marriage lasted 61 long years. died on November 13, 2001, aged 86 at Willow Creek Nursing Home in Clovis in Fresno, California. He had been suffering from Alzheimer’s disease since 1990 according to the release by USAT&F. The funeral took place at St. Anthony’s Catholic Church in Fresno.

On his death the IAAF released a message: “Cornelius Warmerdam…was one of the greatest pole vaulters of all time. He was without doubt the man who marked the era in which just only bamboo poles were used for the pole vault. It took real courage to go so high in those days before the introduction of landing mats, when just a sand pit awaited the athlete’s return to the ground.”

Juanita continued to live in Fresno until her death on Valentine’s Day in 2006. They were survived by five children - Mark, Greg, Gloria, David, and Barry, twenty grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

Unique Legacy

Circumstances and conditions change too much for one era to another for any athlete, no matter how great, to be rated the best of all time in his field. Paavo Nurmi’s fastest time for the mile run was some 20 sec slower than those Sebastian Coe and Steve Ovett ran regularly. If they were contemporaries would anyone really believe that Coe and Ovett would leave Nurmi struggling 150 yards or more back of them.

Thus, comparison based upon unexamined evidence is not justifiable. The truth is that the best an athlete can be is to be the best of his time. Warmerdam was not only without question the best pole vaulter in the world over the seven-year stretch, 1937-1944, but he was also clearly the best pole-vaulter who ever lived.

Thus, comparison based upon unexamined evidence is not justifiable. The truth is that the best an athlete can be is to be the best of his time. Warmerdam was not only without question the best pole vaulter in the world over the seven-year stretch, 1937-1944, but he was also clearly the best pole-vaulter who ever lived.

Of all sports, athletics is one of the most measurable, in that times or distances or heights are accurately taken. However, from one era to another, both psychological and physical changes negate realistic comparisons among champions whose respective careers were separated by many years. The main psychological aspect is that once an unattainable feat is accomplished by one athlete the others know it can be done, and almost immediately they too do it.

Not even the best of the very great runners of the distance could break the four-minute barrier for the mile until Roger Bannister finally achieved it, but since then, it became commonplace and today a four-minute mile is even regarded as rather slow. The physical changes that make comparisons between different generations pointless are more obvious. In track, there are things like better running surfaces and completely new and much more arduous training programs.

In the field, virtually completely new events have sprung up as the result of innovative changes either in technique, as in the cases of the “O’Brien Style” in the shot put and the “Fosbury Flop” in the high jump, of changes in equipment, such as the “fiberglass pole” in the pole vault.

However, even when this has occurred in either track or field, almost invariable when a record is set under new conditions it is immediately attracted or beaten by rivals, and only tiny gaps exist between the best performances and the next best.

The outstanding exception to this was Bob Beamon’s astonishing 29’ 2 ¼” long jump in the 1968 Olympics, which cracked the existing record by almost two feet. But that was not only done in the rarefied atmosphere of Mexico City’s high altitude, it also could be considered a once in a lifetime, almost freak miracle, no matter how admirable. In the ensuring years, neither Beaman nor anyone else come close to that distance.

Warmerdam didn’t just out-vault his rivals by the equivalent of a country mile on one or a few occasions: he did it all the time for years. Look at the record: Warmerdam was a very good but not extraordinary college pole vaulter throughout most of his career at Fresno State in the mid-1930s. Those were the days of the bamboo pole, and Warmerdam was a consistent 13’ 6” to 14’ vaulter, which was good enough to win more than his share of college events but not to attract national attention.

In 1944, when he retired from competition, Warmerdam had vaulted 15 feet 43 times in competitions, while no other vaulter cleared the mark a single time. His record of achievement would hold for decades. At the end of the 1997 season, Sergei Bubka, the five-time world champion pole vaulter from Ukraine, had 23 highest vaults.

In the 1960’s, the fiberglass pole took over and everything in the past went out the window, because this pole introduced new factors in mechanics that escalated vaulters to glorious new heights far above anything they dared hope.

That didn’t diminish his accomplishments in the eyes of fellow pole vaulters such as Bob Richards, the second man to clear 15 feet and the 1952 and 1956 Olympic champion. Richards once said: “Warmerdam was part sprinter, part shock-absorber, part acrobat and part strongman.”

Now several of the best of the new breed are climbing to 19 feet, and more power to them. Unless and until another Superman like Dutch Warmerdam comes along, there isn’t a pole vaulter who can be mentioned in the same breath.

(The author is an Associate Professor, International Scholar, winner of Presidential Awards and multiple National Accolades for Academic pursuits. He possesses a PhD, MPhil and double MSc. His email is [email protected])