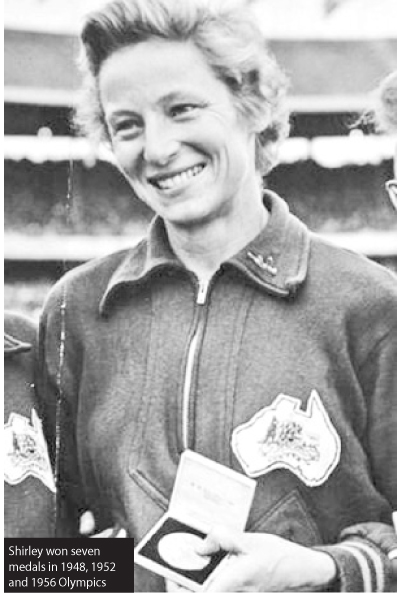

Shirley Strickland, AO, MBE was one of Australia’s greatest athletes, winning seven medals in three successive Olympic Games - London 1948, Helsinki 1952 and Melbourne 1956. Strong, gritty and naturally gifted, she became not only the first Australian female athlete to win three gold medals but also the first female Olympian to win seven multiple medals in athletics.

Shirley Strickland was the daughter of a professional sprinter, and she obviously inherited his father’s speed. Whilst lecturing in mathematics and physics at Perth Technical College, she started to think seriously about athletics. By 1948 she had not only become a national champion sprinter and hurdler, but was considered to be Australia’s top athlete in the team for the London 1948 Olympic Games.

Despite being plagued by personal and professional misfortune, at her first Olympics in 1948, Shirley won a silver in the 4x100m relay and two bronze medals in 100-metre and 80-metre Hurdles. At the 1950 British Empire Games, she won three gold medals in the 80-metre Hurdles, 3x110/220 yards Relay and 4x110/220 yards Relay. She also won two silver medals in the 100 yards and 220 yards.

During her career she set or equalled individual world records in 80m hurdles, and 100m, and she was also a member of the Australian relay teams which set or equalled world records. Then, though juggling a full-time job, marriage and her athletics training schedule, she qualified for the 1952 Australian Olympic team.

In Helsinki 1952 Olympic Games, the Australian sprint hurdler scored her first Olympic gold medal in the 80m hurdles. Besides, she won bronze in the 100-metre. At 30 years of age, she was encouraged to retire to make room for the next generation of competitors. Her determination led to a further two gold medals in the 100-metre and 80-metre Hurdles at Melbourne 1956 Olympic Games.

Birth and parents

Strickland was born on the family farm east of the wheatbelt town of Guildford, Western Australia on July 18, 1925, the only daughter, the second of five children. She grew up in poverty with four brothers. Her mother, Violet Edith Merry, was American-born with a British mining engineer father and a Norwegian mother.

Her father, Dave Strickland, while working at Menzies in the goldfields of Western Australia, was also an athlete. He was unable to compete in the 1900 Summer Olympic Games because he lacked the money for a trip to Paris. Instead, in 1900, he directed his efforts to the Stawell Gift 130-yard (120-m) foot-race, winning in 12 sec off a handicap of 10 yards.

His performance was considered to be as good as those of Stan Rowley, who won the Australian amateur sprint titles that season. Rowley went on to win three bronze medals in the sprints at Paris 1900. Dave Strickland subsequently went on to play one senior game of Australian rules football with Melbourne-based VFL team St Kilda in 1900 and six with WAFL club West Perth spread across the 1901 and 1909 seasons.

University of Western Australia

Strickland’s early education was by correspondence. From 1934 to 1937 she attended the newly established local East Pithara School, winning a scholarship to attend Northam High School, where, she boarded from the age of twelve. In 1939, she won 47 out of 49 events as a schoolgirl athlete.

After high school, she entered the University of Western Australia and wanted to study engineering but was rejected as there were no women’s toilets in that department. Accepted into the Science faculty, she graduated with a Bachelor of Science (Honours) in Physics in 1946.

After high school, she entered the University of Western Australia and wanted to study engineering but was rejected as there were no women’s toilets in that department. Accepted into the Science faculty, she graduated with a Bachelor of Science (Honours) in Physics in 1946.

In her spare time, she lectured in mathematics and physics to returned servicemen at Perth Technical College, played wing in the university hockey team and gained a reputation as an extremely gifted sprinter and hurdler. She also coached track and field.

The World War II was disruptive to women’s athletics in Australia. Some athletes, including Shirley Strickland, enlisted to help the war effort. She was coached by Austin Robertson, a former world professional sprint champion and South Melbourne footballer.

She improved her 100 yards time from 11.8 sec to 11.0 sec. Strickland took up serious running in 1947. At the 1947 Western Australia state titles, she rose to prominence won the 100 yards, 220 yards, 440 yards, the 90 m yards hurdles and the shot put. Her clubs included the University of Western Australia, Applecross and Melville.

London 1948 Olympic Games

In 1948, she took up running seriously, and at the 1948 Australian Athletic Championships she excelled as a sprinter and a hurdler with great success. She won the national title in the 80-metre hurdles, setting a new record of 11.6 sec.

After just one year of competition, she was Australia’s number one athlete and was automatically selected for the London 1948 Olympic Games. She won three medals - silver for the 4x100 metre relay and bronze in the 100-metre sprint and 80-metre hurdles, prompting one sportswriter to comment, “She is one of the finest athletes in the world.”

Strickland finished third in both the 100m and 80m hurdles and won a silver medal in the 4x100m relay, becoming the first Australian female athlete to win a track and field medal. Despite being awarded 4th place in the 200m final, a photo finish of the race that was not consulted at the time, when examined in 1975, showed that she had beaten American Audrey Patterson into third place, a discrepancy that has been recognised by many reputable Olympic historians.

Strickland had never run-on cinders before and had expected them to offer firm footing. With the track soft and very wet, she ended up with cakes of cinders around her shoes. The 100m final was run in blinding rain, with Fanny Blankers-Koen winning in 11.9 sec and Strickland finishing third in 12.2 sec.

The 80m hurdles was incredibly close, with all three (Strickland, Blankers-Koen, and Britain’s Maureen Gardner) finishing in a line. Blankers-Koen was eventually judged the winner with Strickland third with a time of 11.4 sec.

Strickland ran the first leg of the 4x100m relay giving the Australian’s a six-metre lead, however they couldn’t hold onto it and eventually won silver behind the Dutch. Not a bad result considering they had done very little training together. She went on to win more Olympic medals than any other Australian in track events.

Marriage and family

In 1950, she married geologist Lawrence Edmund de la Hunty, who had been one of her students at Perth Technical College. She came to known as Shirley Barbara de la Hunty. They had four children: Phillip (1953), Barbara (1957), Matthew (1960) and David (1963). Lawrence, her husband died of a heart attack in 1980, aged 56.

Amongst the children, Matthew became the lead singer in Australian rock band Tall Tales and True. Barbara graduated in science whilst Phillip graduated with honours in science. David became an ophthalmologist.

By the time the 1950 Commonwealth Games (then British Empire Games) came around a new champion had emerged, Marjorie Jackson but Strickland managed to win three gold medals in the 80m hurdles, 440yds medley relay, and the 660yds medley relays and secure two silver medals in the 100yds and 220yds.

Helsinki 1952 Olympic Games

At the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games, Shirley de la Hunty won her first Olympic title in the 80m hurdles, blitzing the field in world record times of 11.0 sec on July 23, 1952 and 10.9 sec on July 24, 1952. She also won a bronze medal in the 100m sprint behind Marjorie Jackson.

The world record of 46.1 sec in 4x100m Relay was set on July 27, 1952 in Helsinki (Shirley de la Hunty, Verna Johnston, Winsome Cripps, Marjorie Jackson).

Unfortunately, Winsome Cripps dropped the baton in the 4x100 metre relay, denying Australia and Strickland a certain gold medal.

By this time, Shirley Strickland had married and was known as Shirley de la Hunty. She gave birth to her first child in 1953 but was back in peak condition in 1954. Regrettably, she missed out on the 1954 Empire Games team when she misheard the starting gun in the hurdles.

On August 4, 1955, Strickland set a new world record of 11.3 sec for the 100m in Warsaw, Poland and won the 80m hurdles. She achieved her Personal Best performances in the years 1955 and 1956; 100m -11.3 sec and 200m – 24.1 sec (both in 1955), 400m – 56.6 sec and 80m Hurdles – 10.89 sec (both in 1956).

Melbourne 1956 Olympic Games

Shirley de la Hunty was determined to defend her Olympic title on home turf in the Melbourne 1956 Olympic Games despite accusations that she was too old. Described as a housewife (ignoring her thesis on cosmic particle detection) the 31-year-old mother with a three-year-old son, won a gold medal in her event, the 80-metre hurdles, setting a new Olympic record of 10.7 sec.

She also won gold with the Australian 4x100m relay team (Shirley de la Hunty, Norma Croker, Fleur Mellor, Betty Cuthbert) improving the world record twice – firstly to 44.9 sec and secondly to 44.5 sec on December 1, 1956 in Melbourne

This achievement was especially noteworthy for it challenged the notion that once women had children their sporting careers were over. She became the first Australian woman to win track gold medals in the same event at three consecutive Olympic Games.

Most Olympic Medals

Shirley de la Hunty was the only female athlete to have won seven Olympic track and field medals until 1956. This total was equalled by Irena Szewiska-Kirszenstein in 1976 and Merlene Ottey in 1996, and then surpassed by Merlene Ottey-Page with eight medals in Sydney 2000.

After retiring, Shirley de la Hunty maintained her Olympic involvement in athlete administration, as manageress of the Australian women’s team at the Mexico 1968 and Montreal 1976 Olympic Games. She also maintained her interest in sport by coaching athletes including sprinter Raelene Boyle for the 1976 Olympic season.

After retiring, Shirley de la Hunty maintained her Olympic involvement in athlete administration, as manageress of the Australian women’s team at the Mexico 1968 and Montreal 1976 Olympic Games. She also maintained her interest in sport by coaching athletes including sprinter Raelene Boyle for the 1976 Olympic season.

Along with her husband Edmund de la Hunty, she had a longstanding involvement with the Australian Democrats. She was a founding member, and later served as President of the party’s branch in Western Australia. From the early 1970s through to the mid-1990s, Shirley de la Hunty was a perennial candidate for state and federal political office, although never elected. She stood in six state elections – in 1971, and then in five consecutive elections from 1983 to 1996. In 1983, 1986, and 1996, she stood for the Australian Democrats, while in the remaining years she stood as an independent candidate. She ran for the Legislative Assembly in 1983 (East Melville) and 1993 (Melville), and for the Legislative Council in 1971, 1986, 1989, and 1996.

In total, she contested seven federal elections - four consecutive elections from 1977 to 1984, as well as the 1981 by-election in Curtin, and then in 1993 and 1996. She ran for the House of Representatives in 1981 (Curtin), 1984 (Fremantle), and 1993 (Canning), with the latter being her only independent candidacy at federal level.

At all other elections she contested the Senate, where she was generally placed second or third on the Democrats’ group voting ticket. Although never elected to parliament, Shirley de la Hunty served two periods as a City of Melville councillor, from 1988 to 1996 and from 1999 to 2003.

Honours and Awards

On January 1, 1957, Strickland was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for services to athletics. She was also an ardent conservationist and a National Trust member. ‘Shirley Strickland Reserve’ in Ardross, a suburb of Perth, is named in her honour.

After retiring she moved into coaching. Despite her success at coaching, she was never selected as accompanying coach to an Australian team, a fact which she attributed to the male-dominated sports administration.

By the 1970s she began to pursue a new passion - the environment. She was a founding member of the Tree Society and conceived and initiated the Conservation Council of Western Australia Inc. as a forum for nature conservation groups. She was also a founding member of the Australian Conservation Foundation.

Strickland was inducted into the Sport Australia ‘Hall of Fame’ in 1985 as an Athlete Member for her contribution to the sport of athletics and was elevated to ‘Legend of Australian Sport’ in 1995.

Strickland was one of several female Australian Olympians who carried the Olympic Flame at the Opening Ceremony of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. As one of the runners for the final segment, she carried the Olympic torch in the stadium, before the lighting of the Olympic flame.

On January 26, 2001 she was appointed Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for service to the community, particularly in the areas of conservation, the environment and local government, and to athletics as an athlete, coach and administrator.

In 2001, she attracted media attention by auctioning her sporting memorabilia including her Olympic gold medals. She was criticised by some for that but asserted she had a right to do so and the income generated would help pay for her grandchildren’s education and allow a sizeable donation to assist in securing old-growth forests from use by developers. Her memorabilia were eventually acquired for the National Sports Museum in Melbourne by a group of anonymous businessmen who shared her wish that the memorabilia would stay in Australia.

In 2011, Shirley de la Hunty was posthumously inducted among the inaugural inductees into the Western Australia Women’s Hall of Fame. In 2014, Shirley de la Hunty was inducted into the International Association of Athletics Federations’ Hall of Fame.

She became only the third Australian athlete - following Marjorie Jackson-Nelson and Betty Cuthbert - to be inducted into the IAAF Hall of Fame.

Death and funeral

Shirley de la Hunty’s body was found on February 16, 2004 on her kitchen floor in Perth, Western Australia, but the coroner determined that she died on February 11, aged 78. There was no full autopsy and the cause of death was “unascertainable,” though not inconsistent with natural causes.

The Western Australian government honoured her with a state funeral, the first ever for a private citizen. In 2005, some members of her family approached the coroner regarding the circumstances of her death. In 2006, an investigation was conducted by detectives from the major crime squad. In 2008, probate was granted after a dispute over her will was resolved in the state Supreme Court.

(The author is an Associate Professor, International Scholar, winner of Presidential Awards and multiple National Accolades for Academic pursuits. He possesses a PhD, MPhil and double MSc. His email is [email protected])