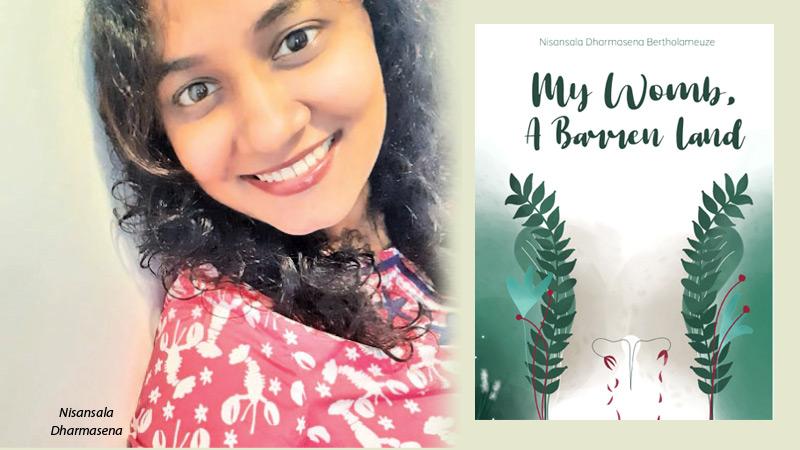

My Womb, a Barren Land by Nisansala Dharmasena Bertholameuze. Colombo: Queeen of Sea Publishers, 2022. ISBN 978 624 5400 01 0. Rs. 2,900.00

Lawrence Ferlinghetti once noted that ‘poetry is eternal graffiti written in the heart of everyone.’ What he meant was, what poetry says and how it might narrate emotions are embedded in all of us as a kind of a universal script.

Differently mentioned, poetry in this sense is something most people can relate to. Nisansala Dharmasena Bertholameuze, the poet of this collection is one of the most passionate young writers and readers of literature of her generation that I know of.

I have always been intrigued by her unusual passion and commitment to literature in general and poetry in particular despite being formally trained in information technology and making a living by teaching that discipline so far removed from the world of words, emotions, and imagination.

Split personality

In my mind, this makes her a poet with a ‘split personality.’ One personality deals with the black and white world of her profession, and the other personality deals with the far more interesting, promising and colorful world of her passion.

Naturally, I deploy the words ‘split personality’ here not in its general sense in psychoanalysis and psychiatry to refer to a disorder, but in a very nuanced and reflective sense to refer to a person who has to consciously negotiate between diametrically opposed worlds to produce something that is endowed with feeling.

Bertholameuze’s poems in ‘My Womb, A Barren Land’ flow across a landscape of intense emotions, navigating through memory, despair, sorrow, and the loss of the ability to express oneself.

There is a certain darkness of emotion in her poems, as most obviously expressed in her poem, ‘As Darkness Descended’:

Last night

As I slit my wrists

Hot blood poured down

Cascading,

As if dancing to the melody of death.

Last night

As the darkness descended

Demons called me by my name

And I went over the edge.

But often, in most of her poems that sense of darkness emerges not like a cloud of desolation devoid of hope, but as a series of reflections in an extended moment of pathos. It seems to me the core theme that cuts across almost all her poems – irrespective of their individual themes – is an implication of memory. As she asks in her poem, ‘A box full of memories,’

Why do we keep such triggers of memories?

Is it for the memories long gone,

Recalled by time,

Or is it for the feeling of been loved

Once cherished

By family,

Friends,

Lovers,

Even strangers

Poetic enterprise

Indeed, ‘Why do we keep such triggers of memories’? Given Bertholameuze’s preoccupation on memory as the foundation for her poetic enterprise in this collection, my effort in this exercise is to outline how memory works from the perspective of my own disciplinary lens and recent work, and to link that understanding with what has been attempted in this collection.

As Eric Kandel notes in his book, ‘In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind’ (2006), recalling the past is not simply bringing into consciousness incidents that took place in bygone times.

More specifically, recalling memory also means experiencing the atmosphere in which something happened, and in that process, reliving in the present the ‘sights, sounds, and smells, the social setting, the time of day, the conversations, the emotional tone’ of those incidents.

Disappointments

To put it differently and more broadly, memory does not mean the accidental or idiosyncratic recalling of the past. As Kandel further, said and commonsense would also inform us, memory brings into our realisation the possibility of continuity of life by stitching the present to the past while at the same time offering a certain coherence to the past.

This process, Kandel said, helps in situating the present in perspective even though the picture that is painted in the present purportedly from the past might not be completely accurate or rational.

The ways in which we recall memory may also work to ‘dilute the emotional impact of traumatic events and disappointments’ of the past, and this process allows people to deal with life in the present.

But this is not the only way in which memory works. It can also work in a contrary fashion, and usher into our present traumatic and painful experiences from the past that might rupture people’s ability to lead what may be called ‘normal’ lives.

It is with reference to such a traumatic collective event – the partition of India and Pakistan – that Suvir Kaul argues for in the book, ‘The Partitions of Memory: The Afterlife of the Division of India’ (2001) the need to catalogue what individuals who experienced the extreme disruptions of the partition could recall.

For him, such a collection of individual memories is crucial because such ‘unofficial’ accounts of people lead to the formulation of an ‘invaluable historical archive’ that would transgress the official memory of both India and Pakistan as well as the more dominant narratives of that same past shared by many others without any seeming contradictions.

In a very broad sense, these are the ways in which memory works. Irrespective of the variations of its recalling or ultimate narrative formats and whether such recalled memories are those of individuals or collectives, memory is not supposed to be complete.

It is often fragmented, reinterpreted, and even reinvented. Memory that manifests in this way is what offers humans the kind of existence they have collectively experienced over time amidst mega histories, civilisational epochs, lengthy moments of chaos, and personal loss, individual sorrow as well as elation at the level of the self.

It is memory in this sense that Bertholameuze also deals with in her work. However, unlike scholars who might end up diminishing the urgency of memory and its share ability in the realms of their tedious scholarship, poets such as Bertholameuze can deal with memory and experiences linked to it more creatively, retaining the immediacy of experience even when dealing with moments of the distant and fading past.

Memory

That is because unlike scholarship, poetry can bring to its readers’ consciousness emotions and feelings they evoke in the way language, metaphors, experiences, memories, and imagination have been used. This is what Bertholameuze also does in her poems.

While what is articulated through her poetry can well be Bertholameuze’s own memories and experiences or what she has seen in the travels of her life or what she has imagined, they do not necessarily have to be seen merely as the emotions of the poet.

As one reads through these poems, what crucially emerges from them is that the feelings they narrate are familiar as if they are our own or that they might well be emotions of our time, the emotions of our friends, the emotions of strangers we pass by in the street or even the emotions of the nation, particularly in the present moment.

But these possibilities of a broader sense of feeling does not time diminish the possibility that these can also be the anxieties of the self – whether that self is the poet herself or each of us who read her work. The emotions that these poems deal with are sometimes very openly acknowledged as the poet does in her powerful poem, ‘My Womb, A Barren Land’:

My Womb, A barren land

Where no child ever played

No smile ever heard

No laughter ever sprinkled love….

…. Yes, My Womb is a Barren Land

Yet,

My Heart ,

My Heart is where everything was,

Everything is.

Yet at other times, these emotions are not always openly acknowledged, but referred to symbolically, poetically, and almost in code more like signs hidden in the crevices of memory and shadows of the sub-conscience. Even so, these narratives are not undecipherable.

Emotional

In her overall exercise, Bertholameuze drags these emotions from their unarticulated and often invisible comfort zones, emotional hiding places and fading moments of the past into the glare of the public domain, assuming perhaps that the journey from the words and the worlds of private suffering and anxiety to the limelight of the public sphere might be a process of catharsis – for the person and collective.

In that process, it seems to me that Bertholameuze fulfils Pablo Neruda’s belief that ‘poetry is an act of peace.’

Adapted from the Foreword to ‘My Womb, A Barren Land’