In Sri Lanka, it is not surprising that a writer and a journalist reside in one person. The surprise is that a sports jounalist and a poet reside in one person. The reason is our sports journalists are just journalists without any literary taste or talent. But this is not case with America. Not only do American sports jounalists read books, but also create literary works. Recently, such veteran poet journalist died in USA. He is Roger Angell who is a briliant baseball writer and poet.

“He kept writing”

Roger Angell (pronounced angel) worked for the New Yorker magazine over six decades, and covered the game in a fresh and innovative way that inspired generations of writers. Considering his creativity in poetry combined with journalistic skills, he was often described as the poet laureate of baseball. But he disliked it, saying that he was a reporter who wrote from a fan’s perspective.

He was at 101 when he died, another surprise. He passed away on May 20 at his home in Manhattan, and the cause for the death was congestive heart failure.

“No one lives forever, but you’d be forgiven for thinking that Roger had a good shot at it,” New Yorker Editor David Remnick wrote about the obituary. “Like the rest of us, he suffered pain and loss and doubt, but he usually kept the blues at bay, always looking forward; he kept writing, reading, memorizing new poems, forming new relationships.”

Colourful language

Roger Angell’s trademark of writing is his colourful language. According to the BBC journalist Robert Plummer, whether he was describing a particular team as “a troupe of gazelles depicted by a Balkan corps de ballet” or referring to the “habitual aura of glowering intensity” of a favourite pitcher, it was his colourful language that brought his reports to life, especially in his regular end-of-season essays.

London-based journalist and writer Michael Goldfarb was quoted in the BBC where he said Angell was to baseball what writers CLR James and John Arlott were to cricket.

London-based journalist and writer Michael Goldfarb was quoted in the BBC where he said Angell was to baseball what writers CLR James and John Arlott were to cricket.

“You couldn’t help but be a little jealous of his ability to insert some highbrow literary metaphor into a description of, basically, a game,” Goldfarb said.

“The guy was genuinely productive for a very long time, and longevity confers mystique.”

In an interview with a journalist in 1982, Angell said: “I think the real fans are the fans of terrible teams, because they know what good baseball is and they know how far their own players fall short.”

The other characteristic of his writing is his point of view. Mostly, he wrote in the first person. Following is an example for it:

“I’ve endured a few knocks but missed worse,” he wrote. “The pains and insults are bearable. My conversation may be full of holes and pauses, but I’ve learned to dispatch a private Apache scout ahead into the next sentence, the one coming up, to see if there are any vacant names or verbs in the landscape up there. If he sends back a warning, I’ll pause meaningfully, duh, until something else comes to mind.”

Among the best of America

As per The New York Times (NYT) journalist Dwight Garner, Roger Angell is the elegant and thoughtful baseball writer who was widely considered among the best America has produced. His voice was original because he wrote more like a fan than a sports journalist, loading his articles with inventive imagery.

When the Boston Red Sox catcher Carlton Fisk came out of his crouch, Mr. Angell wrote, he came out like “an aluminum extension ladder stretching for the house eaves.” For him, the Baltimore Oriole relief pitcher Dick Hall pitched “with an awkward, sidewise motion that suggests a man feeling under his bed for a lost collar stud.”

He described Willie Mays chasing down a ball hit to deep center field as “running so hard and so far that the ball itself seems to stop in the air and wait for him.”

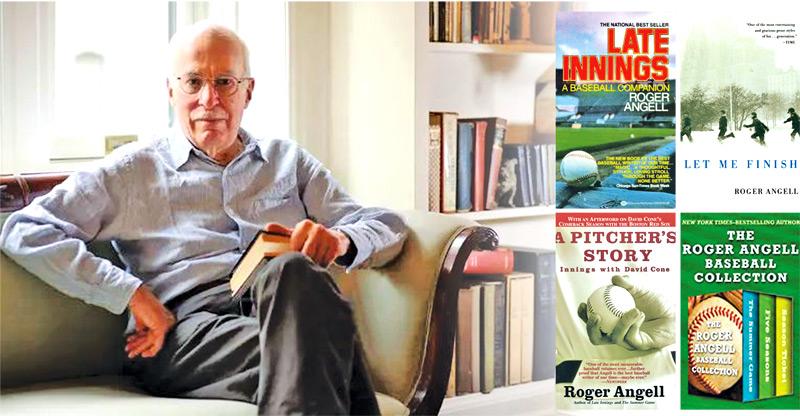

The NYT journalist further notes that the baseball season didn’t seem complete until Mr. Angell wrapped up its multiple meanings in a long New Yorker article. Anyway, many of his pieces are collected in books, among them “Late Innings” (1982) and “Once More Around the Park” (1991).

Angell wrote not just about teams and the games they played, but also considered what it meant to be a fan.

“It is foolish and childish, on the face of it, to affiliate ourselves with anything so insignificant and patently contrived and commercially exploitative as a professional sports team,” he wrote in his book “Five Seasons” (1977). “What is left out of this calculation, it seems to me, is the business of caring — caring deeply and passionately, really caring — which is a capacity or an emotion that has almost gone out of our lives.”

Beginning

Angell was born into a literary family in New York in September 1920. He is the son of Katharine and Ernest Angell, an attorney who became head of the American Civil Liberties Union. His parents were gifted and strong, apparently too strong. “What a marriage that must have been,” Roger Angell wrote in “Let Me Finish,” a book of essays published in 2006, “stuffed with sex and brilliance and psychic murder, and imparting a lasting unease.”

But their marriage was disrupted within few years.

The New Yorker was founded five years after his birth in 1925. His mother Katharine was its founding fiction editor, and a young wit named Andy White (as E.B. White was known to his friends) contributed humour pieces. The co-work at the magazine gave in a close relationship between mother and White. So they got married in 1929. White is a gentler and supportive person for Angell. As he recalled later, when he visited the apartment of his mother and her new husband in weekend, it was a place “full of laughing, chain-smoking young writers and artists from The New Yorker.”

Naturally influenced by legacy of parents, Angell began to publish his writing in the magazine when he was 24 or the year 1944. The first piece he published was his short story titled “Three Ladies in the Morning.” His first words to appear in the magazine were “The midtown hotel restaurant was almost empty at 11:30 in the morning.” Since then, he started to write to the magazine continously, and that went on even in his 90s.

A full-time journalist

When he joined the New Yorker staff as a full-time journalist it was in 1956. But his main job in it was fiction editing. As he was a talented writer himself, there he could discover and nurture writers such as Ann Beattie, Bobbie Ann Mason and Garrison Keillor. For a while he occupied his mother’s old office as well — an experience, he told an interviewer, that was “the weirdest thing in the world.” He also worked closely with writers like Vladimir Nabokov, John Updike, Donald Barthelme, Ruth Jhabvala and V.S. Pritchett.

Angell’s family is a totally literary one. So, automatically, he lived up to the standards of his famous family. He was a past winner of the BBWAA Career Excellence Award, formerly the J.G. Taylor Spink Award, for meritorious contributions to baseball writing, an honor previously given to Red Smith, Ring Lardner and Damon Runyon among others. He was the first winner of the prize who was not a member of the organization that votes for it, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America.

AP writes, “His editing alone was a lifetime achievement.”

Brendan Gill spoke of Angell: “Unlike his colleagues, he is intensely competitive. Here at the New Yorker,” a 1975 memoir. “Any challenge, mental or physical, exhilarates him.”

His writings

Angell’s writings are included in many of his books. His New Yorker writings are compiled in several baseball books and in such publications as “The Stone Arbor and Other Stories” and “A Day in the Life of Roger Angell,” a collection of his humour pieces. He also edited “Nothing But You: Love Stories From The New Yorker” and for years wrote an annual Christmas poem for the magazine. Even at age 93, he completed one of his most highly praised essays, the deeply personal “This Old Man,” winner of a National Magazine Award.

E.B. White encouraged Angell to write for the magazine. He even recommended him to The New Yorker’s founder, Harold Ross, explaining that Angell “lacks practical experience but he has the goods.” In fact, Angell and White had a very close relationship for almost 60 years, and Angell recalled that “the sense of home and informal attachment” he got from White’s writings was “even more powerful than it was for his other readers.”

Allegations

However, not everyone was charmed by Angell or by the White-Angell family connection at The New Yorker. As per AP, former staff writer Renata Adler alleged that Angell “established an overt, superficially jocular state of war with the rest of the magazine.” Grumbling about nepotism was not uncommon, and Tom Wolfe mocked his “cachet” at a magazine where his mother and stepfather were charter members. “It all locks, assured, into place,” Wolfe wrote.

We all know that E.B. White is a major children’s book author. Especially, children’s classics such as “Charlotte’s Web” and “Stuart Little” were written by him. Yet, Angell never wrote a major novel in his long literary life. However, he did enjoy a loyal following through his humour writing and his baseball essays, which placed him in the pantheon with both professional sports journalists and with John Updike, James Thurber and other moonlighting literary writers. Like Updike, he didn’t alter his prose style for baseball, but demonstrated how well the game was suited for a life of the mind.

“Baseball is not life itself, although the resemblance keeps coming up,” Angell wrote in “La Vida,” a 1987 essay. “It’s probably a good idea to keep the two sorted out, but old fans, if they’re anything like me, can’t help noticing how cunningly our game replicates a larger schedule, with its beguiling April optimism; the cheerful roughhouse of June; the grinding, serious, unending (surely) business of midsummer; the September settling of accounts ... and then the abrupt running-down of autumn, when we wish for -- almost demand -- a prolonged and glittering final adventure just before the curtain.”

Accidental sports writer and a holiday poem writer

Angell began covering baseball somewhat later in his career. It was by accident. The New Yorker editor William Shawn was seeking to expand its readership and he wanted more sports articles. Already, Angell was a baseball fan. Shawn asked him to “go down to spring training and see what you find.”

It was an auspicious year to be a young baseball writer: the first season of the New York Mets. “They were these terrific losers that New York took to its heart,” Angell said later in an interview with Salon. So he switched to writing about baseball in 1962.

According to the NYT, Angell was also known for his annual page-long holiday poem, titled “Greetings, Friends!” The poem, a New Yorker tradition, began in 1932, originally written by Frank Sullivan.

Then, Angell wrote “Greetings, Friends!” from 1976 until 1998, when it went on hiatus, and restarted it in 2008. In recent years, the poem has been written by Ian Frazier. Some of his rhymes could be read mischievously. “Yo! Santa man, grab some sky,” he wrote in 1992, “And drop a sock on Robert Bly.”

The New Yorker’s editor, David Remnick, spoke about Angell’s art of writing as below:

“I’m not sure there’s ever been a writer so strong, and an editor so important, all at once, at a magazine since the days of H.L. Mencken running The American Mercury,” he said, “Roger was a vigorous editor, and an intellect with broad tastes.”

In his New York Times article, Dwight Garner discusses Angell’s writing style. Once Angell revealed the tone of his baseball writing was inspired by a now canonical John Updike article, written in 1960, about Ted Williams’s final game at Fenway Park in Boston. “My own baseball writing was still two years away when I first read ‘Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,’” he wrote, “and though it took me a while to become aware of it, John had already supplied my tone, while also seeming to invite me to try for a good sentence now and then, down the line.”

Never losing the sight of baseball’s place

According to the London-based journalist and writer Michael Goldfarb, although Angell was a privileged part of an “extraordinary New York intellectual milieu that no longer exists in quite the same way”, he never lost sight of baseball’s place in American society.

“He didn’t layer sociology on it, but there was always a broad social context,” he added.

Paris-based veteran US journalist Bill Hinchberger says that Angell explored “the relationship between the society and the game”. He told the BBC that when Angell started writing, baseball was seen as America’s national pastime, a status that has since been eroded by the rise of American football and basketball.

He also said: “The way I learned to start using language was reading people like Angell. I was already interested in the subject matter, but it’s a whole different level of engagement when the writing is that good.”

As per BBC journalist Robert Plummer, Angell belonged to a 20th Century US literary tradition in which writers such as Norman Mailer, Damon Runyon and Hunter S Thompson wrote about sports in addition to their fiction and other journalism.

“There were a lot of colourful writers who wrote about baseball or boxing,” Hinchberger said in The New York Times. “I think today, people are more specialised. I couldn’t think of a literary figure right now who does that.”

Personal life

Roger Angell married thrice: his first wife was Evelyn Baker, whom he divorced in 1963. The following year he married Carol Rogge, who taught reading at the private Brearley School in Manhattan and who died in 2012. In 2014, he married Ms. Moorman, a writer and retired teacher.

In addition to her, he is survived by a son, John Henry, whom Angell and his second wife, Carol, adopted; a stepdaughter, Emma Quaytman, through his marriage to Moorman; a brother, Christopher; a sister, Abigail Angell Canfield; three granddaughters; and two great-granddaughters. A daughter from his first marriage, Callie Angell, died by suicide in 2010, while another daughter from that marriage, Alice Angell, died of cancer in 2019.