Nobel Prize winning author Günter Grass is considered a foremost novelist in Germany. With combination of artistic skills, he wrote novels, poetry, essays, plays, and created sculptures and graphic arts as well.

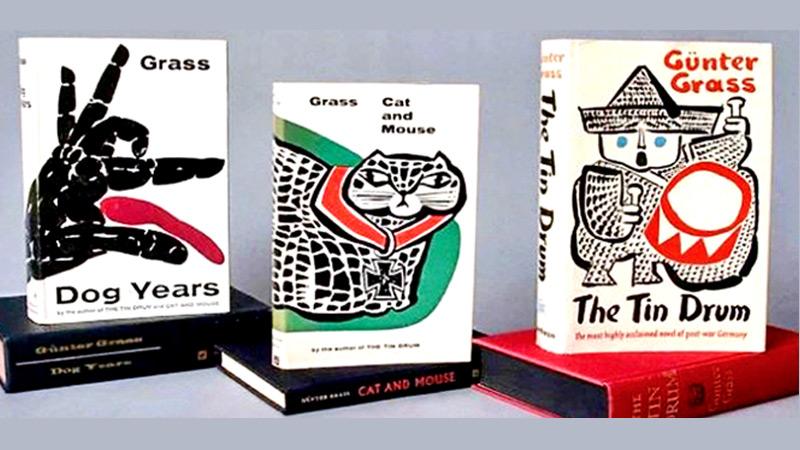

However, he is best known for his Danzig trilogy - ‘The Tin Drum’ (1958), ‘Cat and Mouse’ (1961) and Dog Years (1963). Among his other novels include ‘From the Diary of a Snail’ (1972), ‘The Flounder’ (1977), ‘The Meeting at Telgte’ (1979), ‘Head Births, or The Germans are Dying Out’ (1980), ‘The Rat’ (1986), and ‘Show Your Tongue’ (1989). He is also known for designing his own book jackets and illustrations.

However, he is best known for his Danzig trilogy - ‘The Tin Drum’ (1958), ‘Cat and Mouse’ (1961) and Dog Years (1963). Among his other novels include ‘From the Diary of a Snail’ (1972), ‘The Flounder’ (1977), ‘The Meeting at Telgte’ (1979), ‘Head Births, or The Germans are Dying Out’ (1980), ‘The Rat’ (1986), and ‘Show Your Tongue’ (1989). He is also known for designing his own book jackets and illustrations.

Grass was born in 1927 on the Baltic Coast, in a suburb of the Free City of Danzig, now Gdansk, Poland. His parents were grocers. During World War II he served in the German Army as a tank gunner, and was wounded and captured by American forces in 1945.

Grass was born in 1927 on the Baltic Coast, in a suburb of the Free City of Danzig, now Gdansk, Poland. His parents were grocers. During World War II he served in the German Army as a tank gunner, and was wounded and captured by American forces in 1945.

After his release, he worked in a chalk mine and then studied art in Düsseldorf and Berlin. However, two or three years before his death in 2015, he revealed that he was a SS member in Hitler’s army, and this erupted in huge protests in Israel.

And yet, he was a true writer. From 1955 to 1967, he participated in the meetings of Group 47, an informal but influential association of German writers and critics, so called because it first met in September of 1947.

Living on a small stipend from the publishing house Luchterhand, Grass and his family spent the years 1956 to 1959 in Paris, where he wrote ‘The Tin Drum’.

Following are excerpts from the Paris Review interview with him conducted by Elizabeth Gaffney and John Simon in 1991, which show his art of fiction as well as his views on art.

Never finished a book without three versions

My first book was a book of poetry and drawings. Invariably the first drafts of my poems combine drawings and verse, sometimes taking off from an image, sometimes from words. Then, when I was twenty-five years old and could afford to buy a typewriter, I preferred to type with my two-finger system. The first version of The Tin Drum was done just with the typewriter.

Now I’m getting older and though I hear that many of my colleagues are writing with computers, I’ve gone back to writing the first draft by hand.

The first version of The Rat is in a large book of unlined paper, which I got from my printer. When one of my books is about to be published I always ask for one blind copy with blank pages to use for the next manuscript. So, these days the first version is written by hand with drawings and then the second and the third are done on a typewriter.

I have never finished a book without writing three versions. Usually there are four with many corrections.

Be careful with your characters

I made a mistake in writing my first novel, all the characters I had introduced were dead at the end of the first chapter. I couldn’t go on.

This was my first lesson in writing, be careful with your characters.

My way of writing

I write the first draft quickly. If there’s a hole, there’s a hole. The second version is generally very long, detailed, and complete. There are no more holes, but it’s a bit dry. In the third draft I try to regain the spontaneity of the first, and to retain what is essential from the second. This is very difficult.

My schedule

When I’m working on the first version, I write between five and seven pages a day. For the third version, three pages a day. It’s very slow.

I don’t believe in writing at night because it comes too easily. When I read it in the morning it’s not good. I need daylight to begin.

Between nine and ten o’clock I have a long breakfast with reading and music. After breakfast I work, and then take a break for coffee in the afternoon. I start again and finish at seven o’clock in the evening.

Book is done when I am exhausted

When I am working on an epic-length book, the writing process is fairly long. It takes from four to five years to get through all the drafts.

The book is done when I am exhausted.

Discover things neglected by history

Writers are involved not only with their inner, intellectual lives, but also with the process of daily life. For me, writing, drawing, and political activism are three separate pursuits; each has its own intensity. I happen to be especially attuned to and engaged with the society in which I live. Both my writing and my drawing are invariably mixed up with politics, whether I want them to be or not.

No plan to bring politics

I don’t actually set out with a plan to bring politics into something I’m writing. It’s much more that with the third or fourth time I scratch away at a subject, I discover things that have been neglected by history. While I would never write a story that was simply and specifically about some political reality, I see no reason to omit politics, which has such a great, determining power over our lives. It seeps into every aspect of life in one way or another.

A novel begins with a poem

For me poetry is the most important thing. The birth of a novel begins with a poem. I will not say it is ultimately more important, but I can’t do without it. I need it as a starting point.

The relationship of art and writing

Drawing and writing are the primary components of my work, but not the only ones. I also sculpt when I have the time. For me, there is a very clear give-and-take relationship between art and writing. Sometimes this relationship is stronger, other times weaker. In the last few years it has been very strong.

‘Show Your Tongue’, which takes place in Calcutta, is an example of this. I could never have brought that book into existence without drawing. The incredible poverty in Calcutta constantly draws the visitor into situations where language is stifled—you cannot find words. Drawing helped me to find words again while I was there.

Drawing is a medicine

Writing is a genuinely laborious and abstract process. When it is fun, the pleasure is wholly different from the pleasure of drawing. With drawing, I am acutely aware of creating something on a sheet of paper. It is a sensual act, which you cannot say about the act of writing. In fact, I often turn to drawing to recover from the writing.

Writing is like sculpting

It’s a bit like sculpting. With sculpture, you have to work from every side. If you change something here, you have to change something there. Suddenly you change one plane... and the sculpture becomes something. There is some music in it. The same can happen with a piece of writing. I can work for days on the first or second or third draft, or on a long sentence, or just one period. I like periods, as you know. I work and I work and it’s all right.

Everything’s in there, but there’s something heavy about it. Then I make a few changes, which I don’t think are very important, and it works.

This is what I understand happiness to be, something like happiness. It lasts for two or three seconds. Then I look ahead to the next period, and it’s gone.

You should portray the characters

Literary characters, and especially the protagonist who must carry a book, are combinations of many different people, ideas, experiences, all bundled together. As a writer of prose you have to create, invent characters—some you like and others you don’t.

You can only do it successfully if you can get portray these people. If I don’t understand my own creations from the inside, they will be paper figures, nothing more.

Characters have independent existence

When I begin a book I develop sketches of several different characters. As my work on the book progresses, these fictive characters often begin to live their own lives. For example, in The Rat I had never planned to reintroduce Matzerath as a sixty-year-old man. But he presented himself to me, kept asking to be included, saying, I am still here; this is also my story.

He wanted to picture the book. I have often found that over the course of years, these invented people begin to make demands, contradict me, or even refuse to allow themselves to be used. One is well advised to take heed of these people now and then.

Of course, one must also listen to one’s self. It becomes a kind of dialogue, sometimes a very heated one. It is cooperation.

In my fiction there is poetry

I don’t see any reason to isolate poetry from prose, especially when we have in the German literary tradition such a wonderful mixture of the two genres. I have become increasingly interested in putting poetry between the chapters and using it to define the texture of the prose.

Besides, there’s the chance that prose readers who have the feeling that “poetry is too heavy for me” will see how much simpler and easier poetry can sometimes be than prose.

Explanation has nothing to do with art

I hate explanations. I invite you to make your own picture. In Germany the high-schoolchildren come to school and what they want is to read a good story or a book with a redhead in it. But that’s not allowed. Instead they are instructed to interpret every poem, every page, to discover what the poet is saying.

This has nothing to do with art. You can explain a technical thing and its function, but a picture or a poem or a story or a novel has so many possibilities. Every reader creates a poem over again. That’s the reason I hate interpretations and explanations.

Literature has the power to effect change

I don’t think politics should be left to the parties; that would be dangerous. There are so many seminars and conferences on the subject “can literature change the world”. I think literature has the power to effect change. So does art. We’ve changed our habits of seeing as a result of modern art, in ways of which we are barely aware.

Inventions like cubism have provided us with new powers of vision. James Joyce’s introduction of the interior monologue in Ulysses has affected the complexity of our understanding of existence. It’s just that the changes that literature can affect are not measurable. The intercourse between a book and its reader is peaceful and anonymous.

To what extent have books changed people? We don’t know much about this. I can only answer that books have been decisive for me. When I was young, after the war, one of the many books that were important for me was that little volume by Camus and The Myth of Sisyphus.

The famous, mythological hero who is sentenced to roll a stone up a mountain, which inevitably rolls back down to the bottom—traditionally a genuinely tragic figure—was newly interpreted for me by Camus as being happy in his fate.

The continuous, futile-seeming repetition of rolling the stone up the mountain is actually the satisfying act of his existence. He would be unhappy if someone took the stone away from him. That had a great influence on me. I don’t believe in an end goal, I don’t think the stone will ever remain at the top of the mountain.

We can take this myth to be a positive depiction of the human condition, even though it stands in opposition to every form of idealism, including German idealism, and to every ideology.

Every Western ideology promises some ultimate goal—a happy, a just, or a peaceful society. I don’t believe in that. We are things in flux. It may be that the stone always slides away from us and must be rolled back up again, but it’s something we must do; the stone belongs to us.

Compiled by Ravindra Wijewardhane